![]() A screencast is a demonstration of a task carried out in a software application or on a web site for use as a learning aid or for reference.

A screencast is a demonstration of a task carried out in a software application or on a web site for use as a learning aid or for reference.

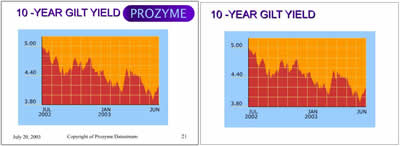

To create a screencast, you simply carry out all the operations involved in completing the task and the software records this as an animation. This animation can be annotated with text labels, accompanied by an audio narration or both. Some authoring tools allow you to go beyond offering simple demonstrations, to provide the learner with opportunities to try out the tasks for themselves using a simulation of the original software.

This 3-part practical guide explores the potential for screencasting, describes the different types of tools available and provides some tips on how to make a good job of your own screencasts.

Media elements

A screencast contains one essential visual element – an animated software demonstration – supplemented by a verbal explanation, presented either as a series of pop-up text labels, an audio narration or as a combination of the two. Typically screencasts are presented as short, self-contained modules or in short sections, to make it easy for the learner to access the material in small chunks and often to practise as they go.

Interactive capability

Many screencasts are passive, presented as short videos which the learner can review quickly and then try out for real. Others incorporate simulations of software tasks which allow the learner to practise without having to leave the screencast and use the real application.

In their passive form, the most likely strategy for the use of screencasts is exploration, as material for use by learners at their own discretion, typically for reference. When simulated tasks are incorporated into the screencasts or when screencasts are combined with other activities that allow the learner to practise what they have learned, they can also play a key role in an instructional strategy.

Applications

Screencasts have two very obvious applications: they can be used as part of a formal training programme to introduce a new or revised software application or web site, or as reference material for people who are already users.

Screencasting tools

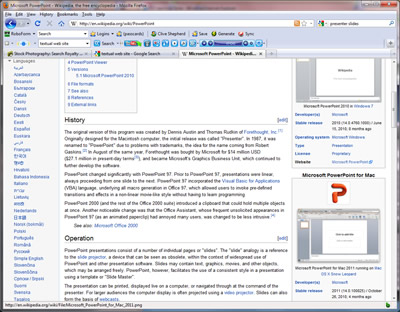

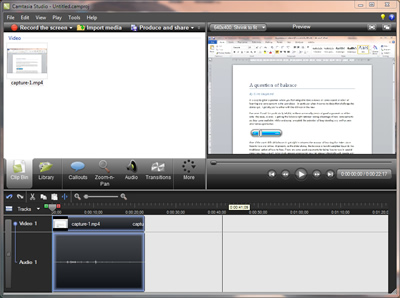

Some screencasting tools have been around for many years, long before the term ‘screencasting’ had been coined. These tools, like Techsmith Camtasia and Adobe Captivate, are desktop applications with sophisticated functionality. Over the years, their capabilities have been increased to support many forms of digital learning content, not just screencasts. These tools allow many ways for the learner to interact with the screencast and to undertake assessments. They also allow the author much greater control over the way in which the screencast is displayed.

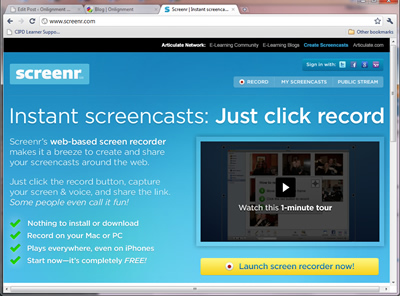

Other, much more recent tools, such as screenr and screenjelly, operate ‘in the cloud’. They allow you to create simple software demonstrations ‘all in one take’ and then to publish these online. In the next part of this guide we’ll be taking a much closer look at these online tools.

Coming next: creating all-in-one-take screencasts

Thanks to Craig Taylor for inspiring this guide with his session at the eLearning Network event on April 8th.