![]() The digital learning tutorial is anything but a new concept. Almost as soon as computers became generally available, efforts were made to automate the process of teaching through the medium of self-study lessons. Under the guise of CBT (computer-based training), interactive video or e-learning, and on a variety of platforms from green-screen mainframe terminals to the early microcomputers, using videodiscs, CD-ROMs, web resources or smart phone apps, the format stays pretty constant – a carefully-crafted sequence of screens displaying learning material and providing opportunities for interaction.

The digital learning tutorial is anything but a new concept. Almost as soon as computers became generally available, efforts were made to automate the process of teaching through the medium of self-study lessons. Under the guise of CBT (computer-based training), interactive video or e-learning, and on a variety of platforms from green-screen mainframe terminals to the early microcomputers, using videodiscs, CD-ROMs, web resources or smart phone apps, the format stays pretty constant – a carefully-crafted sequence of screens displaying learning material and providing opportunities for interaction.

Strange as it may seem, as a result of this long history, instructional designers (those who design these tutorials) are as much a part of the training establishment as those who’ve spent much of their lives in the physical classroom. A handful have been at this task for 30 years or more and they have learned a thing or two along the way. In this practical guide, we’ll attempt to pass on some of the wisdom that has been passed down about the design of learning tutorials, while acknowledging that change is occurring very fast in learning and development and that, as a result, what worked in 1981 when the IBM PC was first launched may not be quite so appropriate in 2011.

So what is a tutorial? The Concise Oxford Dictionary defines a tutorial as “a period of teaching or instruction given by a tutor to an individual or small group.” This hardly sounds like an efficient way of bringing about learning; indeed, only a select group of universities are still prepared to go to this much trouble for their students, and trainers are no different. Luckily, the same dictionary provides another definition: “A tutorial is an account or explanation of a topic, printed or on-screen, intended for private study.” This is nearer to what we’re looking for, but with some of the interactivity, perhaps, that we might find in the face-to-face tutorial.

Media elements

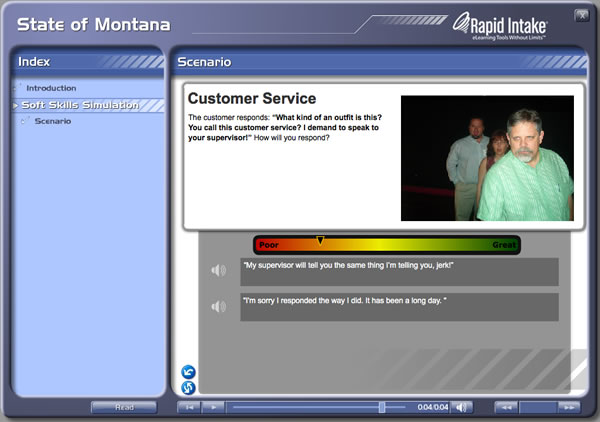

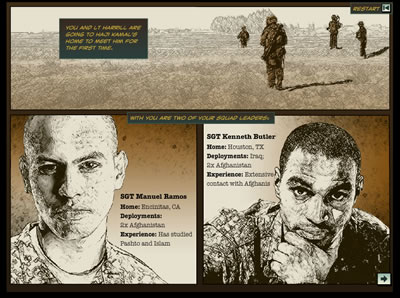

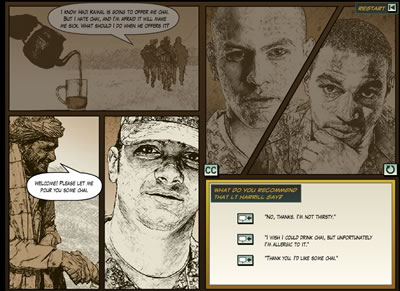

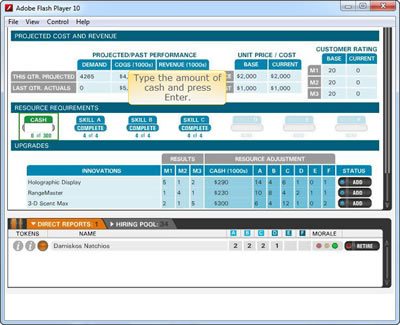

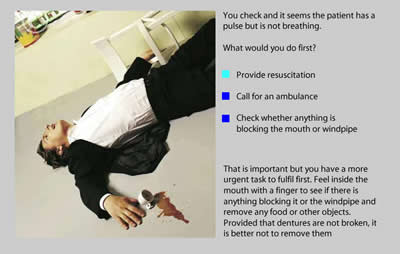

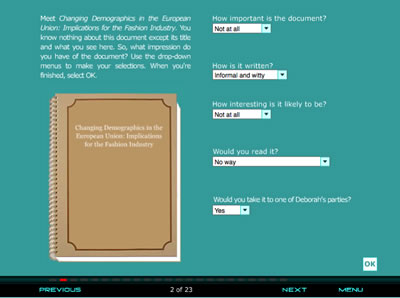

A digital learning tutorial can and frequently does utilise every available media element. Verbal material can be provided in textual form or as audio. Visual material can range from simple photos, illustrations and diagrams through to animations, 3D environments and video. The perfect combination is one that communicates the learning material clearly to the intended audience, while working within the constraints of the available technical infrastructure.

Interactive capability

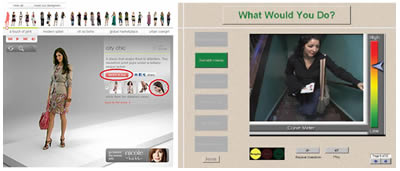

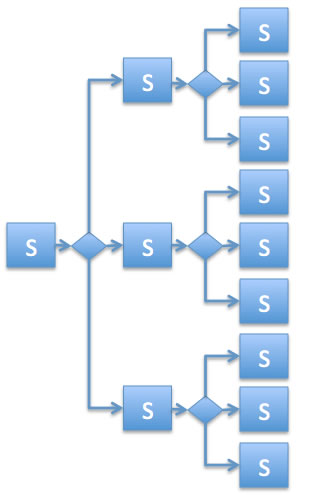

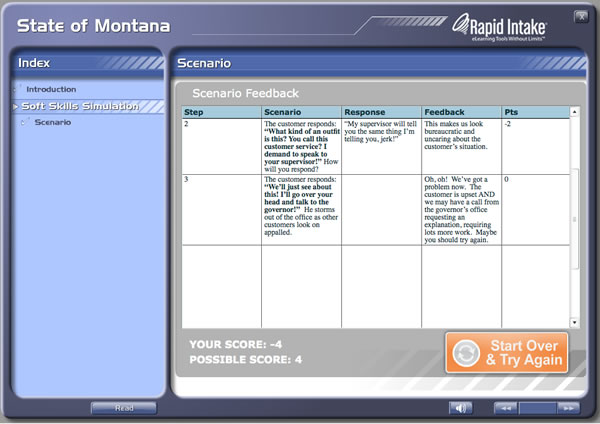

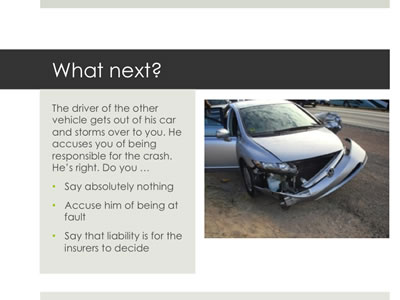

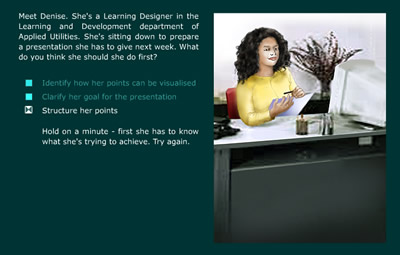

A tutorial is essentially interactive. Screencasts, slide shows, podcasts, videos and all manner of other digital resources can be used effectively without any built-in interaction. Not so a tutorial. Here interaction is the key to what is typically intended as a completely self-contained learning experience. An exposition of learning content followed by a quiz does not constitute a tutorial. To be effective, interaction needs to be integrated into every step of the learning process.

Applications

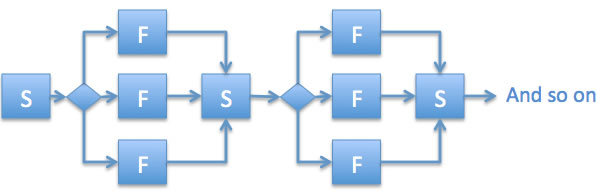

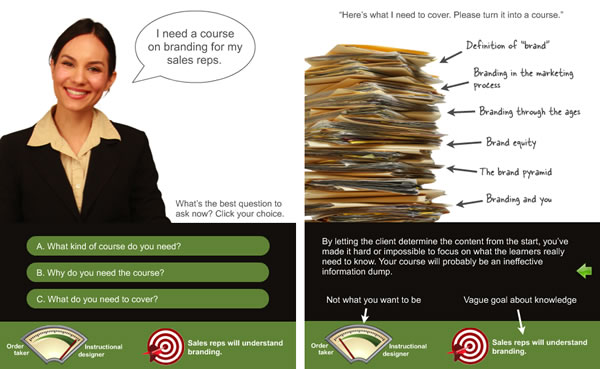

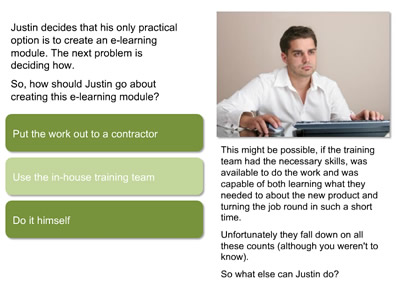

A digital learning tutorial is an instructional device. Instruction is guided by clear objectives. It uses appropriate strategies to support learners as they progress towards these objectives. It is responsive to the difficulties learners may experience along the way. It finishes when the job is done, not when time is up or when all the slides have been shown.

Instruction is particularly valuable when your goal is to provide essential knowledge or to teach rule-based tasks. Designed well, it is capable of providing consistent, measurable results. While those with higher levels of expertise in the topic might find this process laboured, even patronising, novices will be thankful for the structure and support.

So how do I get started?

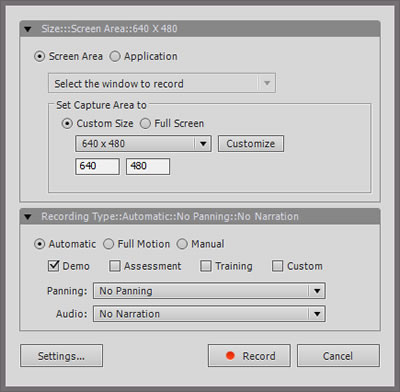

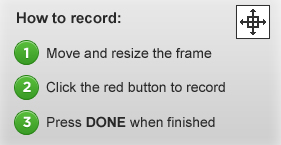

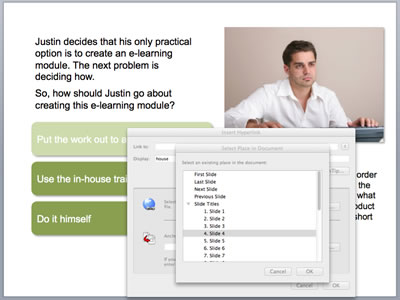

It is possible to create learning tutorials with a general purpose tool like PowerPoint, but you will be severely limited in what you can achieve interactively (you can branch between slides using hyperlinks, but this is a fiddly method to use for anything other than the simplest interactions) and you will not have the functionality necessary to track progress in a learning management system.

The same applies if you use a standard web development tool like Dreamweaver (although, to be fair, Adobe do provide the additional functionality required for building tutorials in a special version of Dreamweaver available as part of their eLearning Suite).

Most people prefer to use a tool that is specially designed to support the development of e-learning. These come in desktop form (Articulate, Captivate, Lectora and many others) and also as online tools available through your web browser. You’ll be looking for a tool that’s easy to use but that is also capable of delivering the level of interactivity that you require.

Much more important than the tool is what you do with it, and that’s what we’re moving on to next.

Coming in part 2: Creating knowledge tutorials