Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 3:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 3:

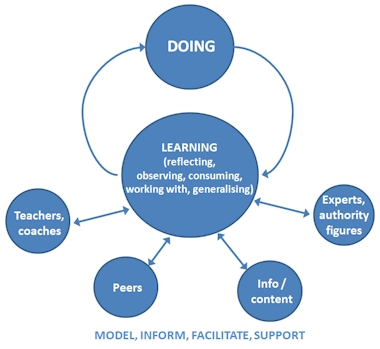

As someone who has chosen to read this book, you presumably have more than a passing interest in helping the learning process on a little, whether directly, by training or creating instructional materials, or by introducing policies that will help learners and their managers to be more effective in their own efforts. So let’s take a break from looking at the process of learning to examine those practices that are likely to provide learners with the most effective support.

First of all, it is worth clarifying once and for all, that learners are not empty vessels into which you can pour whatever knowledge you would like them to have. As we have seen, learners are in the driving seat, not you. They determine what it is to which they pay attention; they decide whether or not to make the effort to transfer what they have learned into long-term memory; it is their mental models into which the new knowledge will be integrated, not yours. There is a massive difference between what is taught and what is learned. As Theodore Roszak explains, “Information is not knowledge. You can mass-produce raw data and incredible quantities of facts and figures. You cannot mass-produce knowledge, which is created by individual minds, drawing on individual experience, separating the significant from the irrelevant, making value judgements.”

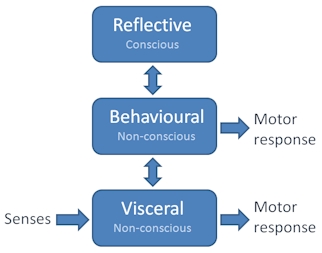

Before you even consider delivering new information, the learner must be in the right emotional state, as Daniel Goleman reminds us: “Students who are anxious, angry or depressed don’t learn. People who are caught in these states do not take in information effectively or deal with it well.”

And with the negative emotions removed, it is just as important to work on the positive, as Berman and Brown emphasise: “It is emotion, not logic, that drives our attention, meaning-making and memory. This implies the importance of eliciting curiosity, suspense, humour, excitement, joy and laughter.”

Norman also sees the value of excitement in learning: “The most powerful learning takes place when well-motivated students get excited by a topic and then struggle with the concepts, learning how to apply them to issues they care about. Yes, struggle: learning is an active, dynamic process and struggle is a part of it. But when students care about something the struggle is enjoyable.”

He goes on: “Students learn best when motivated, when they care. They need to be emotionally involved, to be drawn to the excitement of the topic. This is why examples, diagrams, illustrations, videos and animations are so powerful. Learning need not be a dull and dreary exercise, not even learning about what are normally considered dull and dreary topics.” And how can these topics be made exciting? Well, nothing works better than by making them relevant to the lives of each and every individual student.

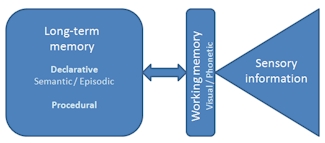

Even the best motivated learner is restricted by the rate at which the brain can cope with new information. Fortunately there is a great deal you can do to minimise the learner’s cognitive load, the burden on their working memory. At a relatively simplistic level you can cut back on the amount of information that learners are exposed to and are expected to acquire at any one time. More often than not, trainers and instructional designers dramatically overestimate the amount of new material that their learners will be able to assimilate. They would do better to break the content down into manageable chunks, remove all unnecessary or redundant material and focus the learner’s attention on the most critical material. Further progress can be made by taking advantage of the ability of working memory to process both visual and auditory information separately, utilising the benefits of self-paced learning, using diagrams to aid understanding, and supplying the learner with materials that they can refer to on-the-job.

Trainers and designers can also help the learner to retain what they learn, to transfer new knowledge to long-term memory. Without this help, there is a danger that much of the new information will be forgotten within hours. Dror encourages setting learners more challenging tasks: “As depth of processing increases, the material will be better remembered. As the learners interact with the material in more cognitively meaningful ways, as they consolidate it with other information in their memory, they are going to remember it better. Rather than using repetition, have the learners make judgements about the material. As the judgements are more complex, depth of processing will increase.”

As mentioned previously, transfer to memory is not enough; the knowledge also needs to be easily retrievable when the need arises. The best way to facilitate retrieval is to fashion practical exercises so they mirror the way that tasks will be carried out on-the-job. Another tactic is to provide knowledge retrieval exercises at intervals throughout the learning process. Practice, supported by specific and immediate feedback, that is managed in this way has many advantages over practice that is massed, not least because learners get the chance to detect and correct any mistakes or misunderstandings at the earliest opportunity.

It is worth reminding ourselves at this point, that the focus of this book is on learning at work, not the process of early development and education. As Bill Sawyer explains, there is a difference: “Well before our consciousness develops into a sense of ‘I’, we are learning machines. We depend upon it for our survival as both individuals and as a species. But learning grows with us. Initially, learning is virtually an automatic process. Before long it begins to take on more and more characteristics of choice. There is still learning by chance or environment, but we begin to take more control over our learning.”

Eventually, the principles of adult learning as defined by Malcolm Knowles come into full effect. As a person matures:

- their self-concept moves from being a dependent personality to a self-directed one;

- their growing experience becomes an important resource for learning;

- their time perspective shifts from one of postponed application of knowledge to the immediacy of the task at hand;

- their motivation to learn comes from within.

Also, as adults we have a significant, long-term investment in the way we are now. Learning is a change and change is a threat to the status quo, to the time, energy and other resources you have expended to become what you are. Resisting change does not make you a Luddite or a ‘difficult person’. Everybody resists some changes and this is only right and proper, because not all change is necessary or beneficial. We would be weak-minded if we simply adopted every suggestion and acted on every order, however senseless.

People don’t actually resist change, in fact we voluntarily and enthusiastically engage in all sorts of massive and highly risky changes throughout our lives. Changes like getting married, having kids, moving from one town or country to another, even changing careers. Clearly these are not trivial changes. It seems that what people actually resist is being changed, that is change that they haven’t instigated for themselves.

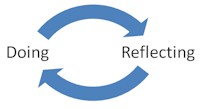

Learning changes the brain, for good. If it doesn’t, then it hasn’t happened. The learner is the gatekeeper to their brain and no amount of lecturing, instructing, prescribed reading or showing of videos will make any difference if the learner is not convinced that they want their brains changed. For the gates to be opened, the learner has to recognise that they have a gap in their knowledge or skills that they believe is worth filling. And they will be much more committed to the process – and the learning will be much deeper – if they have discovered the learning for themselves. The humanist psychologist Carl Rogers once said that “nothing worth learning can be taught”, which is probably going a bit far, but there’s little doubt that learning by doing, conversation, reflection, discovery and inductive (non-directive) questioning will be more effective than simply telling.

References

The Cult of Information by Theodore Roszak, University of California Press, 1994

Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman, Bantam Books, 1995

The Power of Metaphor by Michael Berman and David Brown, Crown House Publishing, 2000

Shall I remember? by Itiel Dror, a paper for Learning Light, 2006

The New Hierarchy by Bill Sawyer, a posting to The Learning Circuits Blog, May 2007

The Adult Learner by Malcolm Knowles, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1973

Coming next in chapter 3: Learning to learn better

Return to Chapter 1

Return to Chapter 2

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth and final part of chapter 3:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth and final part of chapter 3: