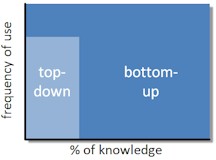

Imagine a scenario where there were no top-down learning interventions, where there was no l&d department and no attempt at all by management to regulate and control the process of learning. Here’s what might happen:

- Employees naturally organise themselves so that, when new employees join the organisation, those with more experience show them the ropes.

- Employees take the initiative themselves to take on new responsibilities or swap responsibilities with others in order to further their development.

- Employees make an effort to share their expertise and experiences with each other.

- In the absence of internal expertise, employees explore what is available externally using their own networks of contacts, resources on the internet, print publications and professional associations.

Sounds good. On the other hand, this might also be the outcome:

- Everyone is so busy that, when a new employee joins, no-one has the time to spend with them.

- Where explanations are provided, the information is so unstructured that novices find it hard to assimilate.

- New employees don’t know what they don’t know, so they don’t ask the right questions.

- Learning is haphazard and critical information is often missed, resulting in accidents, costly mistakes and legal liabilities.

- When changes are made to policies and practices, the benefits are slow to be realised, because the changes are not properly understood.

- Employees are not provided with new challenges, so they get bored and leave.

- When expertise is not available, no-one knows what to do and managers must intervene to resolve the problem.

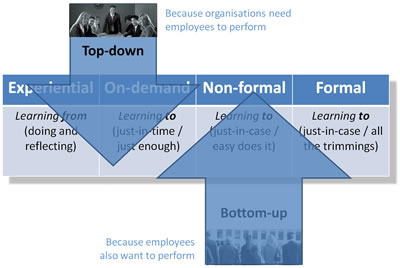

In simple terms, top-down learning is needed to control risk: the risk that employees won’t have the basic competences needed to carry out their jobs; the risk that employees will make costly or dangerous mistakes; the risk that change programmes will fail to meet their objectives; the risk that suitable candidates will not be available when positions become vacant. These are serious risks. Either an organisation has a great deal of trust in its employees to prevent these risks becoming a reality (which may be a sound judgement in exceptional cases), or it must take preventative action itself. And that’s a top-down approach.

Coming next, the third part of chapter 5: How much learning should be top-down?

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect