![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth part of chapter 6:

The most powerful tools in the world won’t help if you don’t have the time or the authority to use them. The second ingredient of an effective bottom-up learning strategy is opportunity:

Discretionary time: Bottom-up learning is in most cases a discretionary activity for which time must be made available. Many employees – particularly knowledge workers – have some degree of discretion about how they spend their time; others are strictly rostered and timetabled and can only participate in bottom-up learning activities outside work hours or in time specially allocated by their managers.

Authority: Time is not the only issue – even with the time, employees have to be allowed to contribute to bottom-up learning, whether that’s through formal organisational policies or the specific inclusion of these activities in their job descriptions. L&d professionals have their role to play here, by making sure that their own policies don’t leave all the power to control the teaching and learning process in their own hands. A good example would be the restrictions that are often placed on the content that can be published on an organisation’s LMS, making it impossible for rapid or user-generated content to be distributed in this way.

Informal spaces provide those without the facility or the inclination to blog with a face-to-face equivalent. Americans talk about the learning that takes place ‘around the water cooler’ and with good reason. Coffee areas and staff restaurants have the same effect, as do the areas where smokers gather to satisfy their addictions. Organisations create these spaces primarily for their functional purpose, but they should also be aware of the learning opportunities that these provide.

Experts in the open: throughout history, humans have learned a great deal by observing experts in their everyday work. Organisations can facilitate this process by arranging workspaces in such a way that novices can work alongside the experts, much as apprentices and their masters have done for centuries.

Coming next in chapter 6: Then they need the motive

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Tag: newlearningarchitect

First they need the means

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 6:

Bottom-up learning will happen to some extent regardless of the efforts put in by the employer to smooth the process. It’s natural for an employee to take the initiative if they don’t know how to complete a task, because they want to do a good job. It will surely be the exception rather than the rule for someone to simply sit down, fold their arms and wait to be told. However, it’s the role of managers – and the l&d specialists who support them – to do more than just leave things to chance. Bottom-up learning can be positively encouraged, by ensuring employees have the means, the opportunity and the motive to contribute to each other’s learning.

Let’s start with the means and in particular the software tools that can provide the infrastructure to support bottom-up learning:

Blogs provide employees with the ability to reflect on their work experiences and to share those reflections with others who have similar work interests. Where an employee has many peers within the organisation, the blogging software can be made available inside the firewall, which has the added benefit of keeping the content away from the prying eyes of competitors. Where an employee works as a specialist and has few internal peers, they may be encouraged to blog on the World Wide Web where they can benefit from the expertise of similar specialists around the world. Assuming they are not critical of the employer – and you would need a policy to cover this – an external blog may even have a positive PR benefit for the organisation, demonstrating thought leadership in a particular discipline.

Search engines are an essential component in any bottom-up learning infrastructure. We all know the power of Google to help us hunt down information and, for any organisation which has an intranet or a substantial collection of online documents, a similarly powerful search facility behind the firewall is essential.

Yellow pages or their software equivalent, allow employees to seek out experts who may be able to help them solve a current problem. If you don’t have the software to do this in a structured fashion, you can always provide a simple list of who to call for what type of information, on the intranet or in hard copy on a notice board. Once an employee has identified the right expert to contact, they need the right communications medium to put forward their question, whether that’s the telephone, email, instant messaging, web conferencing, SMS messaging or some other format. With this proliferation of communication media, organisations might consider issuing some guidelines to help employees choose the right medium for each particular situation.

Forums (or message boards or bulletin boards, as they are sometimes called) provide a simple way for employees to post questions online, with the hope that somewhere in the community another employee will be able to provide a helpful response. Where forums can let you down is when you are depending on other users to visit the forum site in order to see the latest questions. Some element of ‘push’ is required to alert users to new questions, whether that’s email notifications, RSS feeds or lists of recent postings that appear on the intranet home page.

Wikis provide a way for employees to collaborate in creating content that can be of use to the whole community. Although subject experts and l&d professionals may prime a wiki with content, the ability of all employees to make contributions based on their own particular experiences, makes a wiki much more than a simple reference manual.

Learning management systems (LMSs) can help employees to find e-learning content that is available for open access on an ‘as needs’ basis. It’s important to keep the barriers between the employee and the content to a minimum. Ideally employees should not have to log in separately to the LMS; the available content should be sensibly categorised; the content should be tagged so it can be easily found using the LMS’s own search facilities; the registration/sign-up process should be minimal; and employees should be allowed to rate content, so the most popular and useful content is clearly visible.

Social networking is usually seen as an out-of-work activity, where people use software such as Facebook, MySpace or Bebo to maintain their network of contacts for purely social reasons. However, in just a few years, social networking has grown so quickly, and exerted such a powerful influence on its users that many organisations are now looking for ways to achieve similar benefits inside the firewall. An organisation’s own social network could be used to allow employees to connect with others who have similar needs and interests, to find sources of expertise, to form communities of practice and to keep up-to-date on developments in their particular fields.

Of course, tools are not enough in themselves; employees also need the skills to use them. Although many of the tools listed above are extremely easy to use and many employees will be familiar with their use outside work, there is room here for top-down initiatives to ensure all employees know which tool to use in which circumstance and have the confidence to become active users.

In his ‘How to save the world’ blog, Dave Pollard lists a number of ways in which organisations can achieve quick wins with bottom-up knowledge management initiatives, by skilling up employees to make better use of the tools at their disposal:

“Help people manage the content and organisation of their desktop: Most people are hopeless at personal content management but don’t want to admit it. Provide them with a desktop search tool and show them how to use it effectively.

Help people identify and use the most appropriate communication tool: Give them a one-page cheat sheet on when not to use e-mail and why not, and what to use instead. Create a simple ‘tool-chooser’ or decision tree with links to where they can learn more about each tool available.

Teach people how to do research, not just search: If people are going to do their own research, they need to learn how to do it competently. Most of the people I know can’t.”

Coming next in chapter 6: Then they need the opportunity

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Training's long tail

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 6:

The phrase The Long Tail was first coined by Chris Anderson in 2004 to describe the niche strategy of businesses, such as Amazon.com, which sells a large number of unique items in relatively small quantities. Whereas high-street bookshops are forced, by lack of shelf space, to concentrate on the most popular books, shown in the chart below in blue, retailers selling online can afford to service the minority interests shown below in orange. Interestingly, the volume of the minority titles exceeds that of the most popular, yet before the advent of online retailing, these needs would have been very hard to service.

The concept of The Long Tail fits well with the argument for bottom-up learning. Top-down efforts can only seek to address the most common (or, as we have seen, sometimes the most critical) of needs. It is simply not possible, given available resources, for l&d professionals to design and deliver an appropriate solution to satisfy every learning requirement in their organisations. Instead, when it comes to corporate learning and development, it is bottom-up learning that must address training’s long tail.

In the end it comes down to priorities – putting the effort in where the reward is going to be greatest. At risk of over-simplifying the issues involved, you could argue that the prioritisation process could be extended across all eight cells of our model, with the most generic and critical needs met top-down, through formalised courses. Less common/critical needs would be met by less structured proactive methods; if not, then at the point of need; if not, then through a process of structured reflection. As we extend into The Long Tail, bottom-up approaches come to the fore, starting with formal external programmes and continuing across the four contexts:

Tony Karrer argued that: “To play in The Long Tail, corporate learning functions will need to:

- find approaches that have dramatically lower production costs, near zero;

- look for opportunities to get out of the publisher, distributor role such as becoming an aggregator;

- focus on knowledge worker learning skills;

- help knowledge workers rethink what information they consume, how and why;

- focus on maximising the “return of attention” for knowledge workers rather than common measures today such as cost per learner hour.”

References:

The Long Tail by Chris Anderson, Wired, October 2004.

Corporate Learning Long Tail and Attention Crisis by Tony Karrer, eLearning Technology blog, February 19, 2008.

Coming next in chapter 6: First they need the means

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

How much learning should be bottom-up?

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 6:

It is conceivable that an organisation could manage without any top-down learning interventions at all, relying on employees who were independent learners, good communicators, willing to share their expertise and keen to support each other. More realistically, an organisation will need to make a judgement about how much will be top-down and how much bottom-up, based on a wide range of factors that will differ enormously both between organisations and within them. Here are some guidelines for identifying the situations in which bottom-up learning will be most appropriate:

Where there is constant change and fluidity in tasks and goals: Some organisations are lucky enough to enjoy relatively stable policies, procedures and systems; for many others, particularly those which employ a large number of knowledge workers, the opposite is true – everything seems in a constant state of flux. In this situation, it is almost impossible to create top-down interventions fast enough to satisfy the need; you simply must depend on bottom-up processes to fill the gap.

For knowledge and skills that are used infrequently: If we apply the Pareto principle, then it is realistic to assume that 20% of all the knowledge related to a particular job will be adequate to cover 80% of the tasks. The remaining 80% of knowledge is used only occasionally and can probably therefore be handled using more informal, bottom-up methods, including the use of forums, wikis and similar tools. Some care needs to be taken that, within the less-commonly used knowledge and skills, there are none which are nevertheless critical. A good example would be emergency procedures – these should certainly not be left to chance and should therefore be tackled through a formal, top-down intervention.

When expertise is widely distributed: It is hard to place too much emphasis on bottom-up processes when expertise is centred around a small number of key individuals – these people would be simply overwhelmed by the never-ending requests for help that they would inevitably receive. In these situations, it makes more sense to capture this expertise using more structured, top-down methods. On the other hand, there are many situations in which it is true to say that ‘nobody knows everything and everybody knows something’. Where expertise is widely distributed, bottom-up methods are much more likely to thrive.

Where there are fewer people who need the learning: With scarce resources, l&d departments must focus on those needs which are highly critical or which impact on large numbers of people. There are simply not enough hours in the day to create top-down programmes for every small group that has a shared need. Here again, bottom-up methods fill the gap and ensure that needs don’t go unmet.

Where the employees are more experienced: Experienced employees have the advantage of generalised knowledge about situations and events stored in long-term memory, which make it very much easier for them to absorb new information. Whereas novices benefit from more structured learning experiences, in which they are led step-by-step through new information with the aid of an expert facilitator, more experienced employees can be given much more latitude to help themselves.

Coming next in chapter 6: Training’s long tail

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Why bottom-up learning is needed

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the second part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the second part of chapter 6:

Imagine a scenario in which no bottom-up learning took place, in which all learning was regulated and controlled by management, and in which the l&d department invariably took the lead. Here’s what might happen:

- The l&d department knows exactly what knowledge and skills are required for each job position and are kept completely up-to-date about any changes to jobs and requirements.

- Regular performance appraisals and other forms of assessment mean that line management are fully aware of any knowledge and skill gaps, and keep the l&d department fully informed about these.

- The l&d department is resourced to provide solutions to meet all known knowledge and skills gaps, using carefully-planned, top-down interventions.

- Employees do not need to worry about the knowledge and skills they need to meet current or future requirements because their employer is in complete command of the situation.

Sounds like it’s all under control. On the other hand, this might also be the outcome:

- The information held by the l&d department regarding jobs and skills is too out-of-date to be of any use.

- The l&d department does not have the resources to respond to anything except the most generic of needs.

- When important changes are made to systems, processes and policies, the l&d department takes too long to develop top-down interventions to support the changes.

- Knowledge requirements change so quickly that it is impossible for training programmes and job aids to be kept up-to-date.

- There is such a diversity of jobs in the organisation that there is insufficient critical mass to justify the design and delivery of any formal interventions.

- Expensive top-down interventions are delivered when employees are perfectly capable of meeting any needs for themselves informally.

While top-down learning is needed to control risk, bottom-up learning is needed to provide responsiveness. Few organisations have the luxury of being in complete control of all aspects of the training cycle – even if it was possible to attain this position, it would probably not be cost-effective. Bottom-up learning fills the gaps by providing a response to urgent situations and by meeting the needs of minorities. It’s quick, it’s flexible, it’s empowering. That’s why bottom-up learning plays a valuable role in any learning and development strategy.

Coming next in chapter 6: How much learning should be bottom-up?

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

The scope of bottom-up learning

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 6:

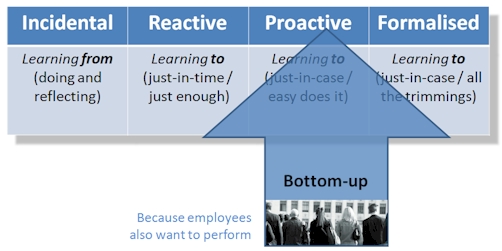

Bottom-up learning occurs because employees want to be able to perform effectively in their jobs. The exact motivation may vary, from achieving job security to earning more money, gaining recognition or obtaining personal fulfilment, but the route to all these is performing well on the job, and employees know as well as their employers that this depends – to some extent at least – on their acquiring the appropriate knowledge and skills.

Bottom-up learning occurs in each of the four contexts that we have described previously:

Experiential: Experiential learning is essentially reflective – ‘learning from’ rather than ‘learning to’. This process can be initiated by the individual without any deliberate action on the behalf of the employer. At its simplest, this might mean no more than sitting back and thinking over events that have occurred, whether these events directly involved the individual or whether they were merely observed. If an event had a negative outcome, the question needs to be asked ‘why did this happen?’ Could the outcome be avoided in future or mitigated in some way. If the outcome was positive, it is just as important to know why. Why can be done to replicate this successful outcome, or to exploit it if it occurs again? The process of reflection becomes interactive when it takes the form of a discussion – talking things over. And it becomes more disciplined when it is made explicit through blogging. Employees can also choose to expand the opportunities they have for learning experiences by ensuring they maintain a healthy work-life balance. Out-of-work activities such as hobbies, travel and voluntary work will often have parallels at work. By maximising the scope for new sensory input, individuals increase the chance that they’ll build valuable skills and insights that they can apply in their jobs.

On-demand: When it comes to just-in-time learning, employees have always needed to rely to some extent on their own endeavours. It is highly unlikely that any employer will be able to predict every item of information that every employee is going to need in every situation, and make that available in the form of some sort of job aid or resource. At simplest, when they’re stuck, employees simply consult an expert, typically the person sitting next to them. Ideally this process will be formalised through some kind of online ‘find an expert’ solution, a sort of corporate Yellow Pages. Increasingly online tools are being made available to support and encourage bottom-up learning at the point of need, notably forums to which questions can be posted, and wikis which can be used to collect together useful reference information.

Non-formal: There’s a number of ways in which employees can set about equipping themselves with the knowledge and skills they need to develop in their roles, without enrolling on formal courses. While each of these methods relies on the employee to initiate the activity, they all tend to require some help from the employer, whether that’s by establishing the appropriate infrastructure or by committing to policies which make opportunities accessible. Some examples include open learning, where the employee takes advantage of learning resources, such as short self-study courses, which the employer makes available for access on demand; social networking software, which allows the learner to establish contacts with others within the organisation who have similar needs; attending external conferences; and enjoying the services provided by professional associations and other external membership bodies.

Formal: You would think that formal courses were an exclusively top-down initiative, but there are plenty of ways in which employees can take the initiative themselves. Perhaps the most obvious examples are postgraduate courses, such as Masters Degrees, and qualifications offered by professional bodies. There are, of course, other less formidable options, such as adult education courses offered by local colleges.

People have many and wide-ranging needs, whether that’s at the level of survival (security, shelter, food, reproduction, etc.), needs of a more social nature (belonging, friendship, recognition) or of a higher order (stimulation, advancement, personal fulfilment, etc.). Directly or indirectly, learning can help an individual to meet many of these needs. To the extent that this learning is reflected in better performance at work, then the organisation has as much to gain as the individual.

While the l&d professional may not determine the ‘content’ of the learning that takes place on a bottom-up basis, they certainly have a role to play in determining the ‘process’. Because it is impractical to meet all learning requirements top-down, it is in the interests of the organisation to encourage relevant, work-related, bottom-up learning. Some of this will happen anyway, regardless of what the l&d department puts in place, but much depends on the right policies and infrastructure being put in place.

Where l&d professionals must be careful, is not being over-prescriptive about the ways in which bottom-up learning occurs. As John Seely Brown and Paul Duquid point out : “The solution to unpredictable demand is systems that are geared to respond to pull from the market and from audiences; built on loosely-coupled modules rather than tightly integrated programmes; people-centric rather than resource or information-centric. There needs to be a willingness to let solutions emerge organically rather than trying to engineer them in advance.”

Reference:

The Social Life of Information by John Seely Brown and Paul Duquid, Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

Coming next in chapter 6: Why bottom-up learning is needed

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Conditions for success

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth and final part of chapter 5:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth and final part of chapter 5:

To summarise, these are the conditions for success with top-down learning:

- Top-down learning interventions are aligned with the business goals of the organisation and measured in terms of the contribution they make to these goals.

- These interventions are designed to meet genuine learning and development needs.

- These interventions are focused on critical and widely used knowledge and skills, and on the needs of novices and those with low metacognitive skills.

- The most resources are allocated to the interventions that deliver the most value to the organisation.

- Senior management is actively involved in determining needs and genuinely committed to helping make learning interventions a success.

- All key stakeholders, including potential learners, are involved in the process of designing and developing the interventions.

- All four contexts (experiential, on-demand, non-formal, formal) are considered in designing the most appropriate form for the interventions.

Coming next, chapter 6: Bottom-up learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Implementing top-down learning interventions

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 5:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 5:

Having determined where the priorities lie for top-down learning interventions, attention inevitably turns to the forms that these interventions should take and the ways in which they can be most successfully delivered. All too often, l&d professionals (often on the insistence of their sponsors in the line) start with the assumption that some sort of formalised course is required, whether classroom, online or a blend. But as we have seen, there are four contexts in which top-down learning could occur. Who is to say that an action learning programme, a performance support system or a programme of coaching would not do the job better or more efficiently?

The chances that an intervention will be successful are influenced by the involvement of key stakeholders in the process of design, development and implementation, as Wick, Pollock, Jefferson and Flanagan report : “We continue to be surprised by the number of major programmes, in otherwise well-managed companies, that are developed entirely within the human resource or training organisation and go forward with little or no input from line leaders. Their perspective on the business is different from that of line leaders; they have less hands-on experience managing hard business metrics. If they consult only among themselves, they may design a programme with strong learning objectives but only weak links to key business measures.”

There is another strong reason for involving those who will be affected by the intervention and that is to gain their commitment. Learning is change. At the personal level, this is true because learning changes the brain – if it doesn’t, no learning has taken place. At an organisational level, it is true because learning changes the way we behave and consequently how the organisation performs. As we have already discussed, people don’t automatically resist change; in fact we voluntarily undertake substantial and disruptive changes in our own lives. As Peter de Jager explains, “We don’t resist change, we resist being changed.” At very least, those being asked to change should be told why. Better still, they should participate in determining how.

The process is not complete, as we are constantly reminded, until we have evaluated the results. First of all it’s important that we know what the reactions of learners has been to our efforts – not because this is the key indicator of success, but because this feedback enables us to continuously improve what we deliver. We do need to know whether the intervention has resulted in the desired change in knowledge and skills and whether that change has manifested itself in the way that learners behave on the job. But most importantly, we need to know whether the organisation is receiving any tangible benefit from these changes. Kirkpatrick calls this a ‘return on expectations (ROE)’. What did the organisation expect when they sanctioned this intervention? Have these expectations been met? It is not necessary to provide incontrovertible proof, based on controlled scientific studies. It is necessary, however, to be able to provide a chain of evidence: we know the intervention was well-received and that participants learned what we wanted them to learn; we know they applied this back on the job and we have seen an improvement in those areas of the business that we were looking to address. That’s as much proof as most managers will ever require.

On the other hand, evaluation studies don’t always capture the true value of learning interventions. As Stephen Downes reminds us: “Measuring learning is still like measuring friendship. You can count friends, or you can count on friends, but not, it seems, both.”

Coming next, the sixth part of chapter 5: Conditions for success

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Targeting top-down learning

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 5:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 5:

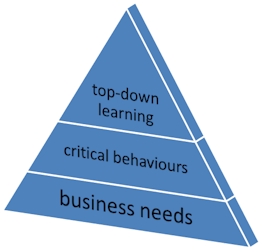

As we’ve seen, given that all l&d professionals operate within a context of limited resources, top-down learning needs to be well targeted. Determining what those targets should be is not a trivial task, particularly as many l&d departments are not that well connected to the managerial decision-making process within their organisations. The effort must be made, however, or else a high proportion of the resources expended in top-down interventions (not least the efforts and talents of committed l&d professionals) will be misdirected, if not completely wasted. As Berry Gordy, founder of Motown Records, famously remarked: “People ask me, ‘where did I go wrong?’ My answer is always the same: Probably at the beginning.”

It is nothing new to be told that training should be aligned to the needs of the business, but that doesn’t mean that it ‘goes without saying’ or is ‘common sense’. All too often, common sense is anything but common. Ask yourself how many of the training interventions in your organisation are clearly aligned to current business needs, rather than fulfilling requirements articulated sometime in the distant past, but which have no current relevance. And how many interventions have originated from the l&d department on the basis of where they believe the organisation should be heading, regardless of the views of senior management? No organisation ever set up an l&d department so this department could then determine the appropriate direction for the organisation. It is not up to l&d professionals to decide what is good leadership, what is good customer service or what are appropriate values for the organisation. Their job is to help senior management make their vision a reality, regardless of whether that vision is shared by the professionals that staff the l&d department.

A good question to ask is this:

What behaviours are critical to the future success of this organisation?

Let’s unpick this a little. You need to know about ‘behaviours’ because, of all the various factors which influence the success of an organisation, only these can be affected by learning and development. You need to find out which are the ‘critical’ behaviours, because you don’t have the resources to devote to the non-critical. And you need to focus on ‘future success’, because learning and development is an investment in the future and can do little to influence what happens right now. The only people who can answer this question with any authority are senior management.

The question can and should also be addressed at each of the main functional and regional departments and divisions within the organisation, as well as at various levels. For example: “What behaviours are critical to the future success of the IT department or European region”; “What middle management behaviours are critical to the future success of the organisation?”

Once you know what behaviours are required if the organisation is to succeed in the future, you need to assess the extent of the task in front of you:

To what degree are employees already exhibiting the behaviours that are critical for success?

Answering this question is no small task. If you work for a larger organisation, then ideally you’ll have set up a performance management system which enables you to keep track of how individuals are performing. This will include a competency framework covering every job position; one that is up-to-date with the constant and inevitable changes in job responsibilities and which describes the behaviours that senior management are looking to encourage. In order for you to assess the extent to which these competences are evidenced in actual performance, all employees will have been regularly assessed against this framework or will have conducted some form of self-assessment. Smaller organisations may not have gone so far, but they should at very least be conducting regular performance appraisals.

If, having carried out your research, you find no gaps, then your only problem is ensuring the continued supply of employees who exhibit the desired behaviours. You should be so lucky! Chances are you’ll have to ask one more question:

What influence can learning and development have on these behaviours?

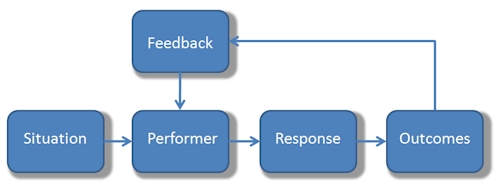

Performance is influenced by a lot more than skill and knowledge, as this diagram shows:

Situational influences on the performer include the clarity of roles and objectives, the suitability of the working environment, and the tools and other resources at the performer’s disposal. The performer him or herself has aptitudes (indicating his or her potential to learn) and motivations, as well as their accumulated knowledge and skills. The performer’s responses are also influenced by outcomes (the incentives and disincentives that are likely to result from performing in a certain way) as well as the timely availability of relevant feedback. The whole performance system has to be functioning correctly if performers are to exhibit the desired behaviours. Learning and development is only going to work if (1) unsatisfactory performance can at least partly be attributed to a lack of knowledge or skills, and (2) the employees in question have the aptitude to acquire these.

According to Stolovitch & Keeps , “The leading human performance authorities have all demonstrated that most performance deficiencies in the workplace are not a result of skill and knowledge gaps. Far more frequently they are due to environmental factors, such as a lack of clear expectations; insufficient and untimely feedback; lack of access to required information; inadequate tools, resources and procedures; inappropriate and even counterproductive incentives; task interference and administrative obstacles that prevent them achieving desired results.”

L&d professionals may have to be assertive in conducting and communicating this sort of logical analysis. As Wick, Pollock, Jefferson and Flanagan remind us, “The problem typically begins when someone in upper management decrees that the company needs to have a programme on some particular topic. And when the goal of having a programme is defined as ‘having a programme’, the initiative is in trouble from the start.” Senior managers may be experts in determining the problems that are getting in the way of performance, but they are not experts in finding the solutions – that’s your job, and this is your time to speak up.

Coming next, the fifth part of chapter 5: Implementing top-down learning interventions

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

How much learning should be top-down?

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 5:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 5:

It’s possible that, where there isn’t that much to know and it doesn’t change that often, all learning can be managed on a top-down basis. However, this is completely unrealistic for the majority of organisations in which there’s far too much to know and it’s changing far too quickly. So where should the priorities be placed?

On the most critical knowledge and skills: Some learning is of high importance, not necessarily because it is required that often, but because if it is not applied on the occasions when it is required then there could be serious consequences for the organisation. Imagine a pilot who didn’t know how to land a plane in bad weather conditions, a financial trader who did not know how to respond to a market crash, a manager who did not realise the implications of firing a direct report who he happened not to like all that much. Some learning simply cannot be left to chance – it needs to be planned carefully, expertly facilitated and rigorously assessed.

On the most commonly-used knowledge and skills: Leaving aside the really critical, high stakes knowledge and skills, a judgement has to be made on how the remainder is handled. One answer is to apply the Pareto principle, also known as the 80:20 rule. This states that, in many situations in life, 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. In a learning context it would be reasonable to assume that 20% of all the knowledge related to a particular job will be adequate to cover 80% of tasks. The remaining 80% of the knowledge is used only occasionally. It makes sense, therefore, to concentrate resources on providing the knowledge that is most regularly needed, whether through a training intervention or the provision of performance support.

On novices: When you have little or no knowledge of a subject, you are more appreciative of a structured and supportive learning environment. Novice learners don’t have the advantage of existing schemas (generalised knowledge about situations and events) in long-term memory that enable more experienced employees to cope with less structured learning experiences. Clark, Nguyen and Sweller explain how carefully-designed instructional approaches “serve as schema substitutes for novice learners. Since novices don’t have relevant schemas, the instruction needs to serve the role that schemas in long-term memory would serve.” The implication of all this is that, if you’re a skilled l&d professional, your services will be most appreciated by novices.

Where metacognitive skills are low: Those with good metacognitive skills are better equipped to learn independently. They have a good feel for what they already know, what’s missing and how to go about filling the gap. They will benefit from top-down learning but they don’t depend on it. For this reason, where resources are tight, efforts are more sensibly directed at those who most need the assistance. There are various ways of finding out who has the ability to learn independently. You could (1) guess based on generalisations (unskilled workers, unlikely; software engineers, likely), (2) observe behaviour over time and come to a considered opinion, person by person, or (3) ask the people involved directly. Just make sure you don’t use the term ‘metacognitive skills’!

Coming next, the fourth part of chapter 5: Targeting top-down learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect