![]()

Another characteristic that will have a big influence on our design is the degree of motivation the target population is likely to have to learn about the topic in question. It is hard to bring about learning without a degree of emotional engagement. Quite simply, when our attention is aroused we remember much more.

If you know that learners will be coming to your programme full of enthusiasm, you have the luxury of being able to get straight on with the teaching, without much in the way of preliminaries. More often, learners need some convincing to devote time in their busy lives to what you have to teach. It is possible they have no choice about whether or not they go through your programme and are feeling just a bit resentful. In situations like this you have to build into your design the steps necessary to overcome these obstacles. You need to show why the topic in question is relevant to the learner’s working life and why time spent engaging with it will yield real benefits.

Next up: Of course it’s not that simple

Tag: blending

7. The importance of prior learning

![]()

As we’ve discussed above, learning, both formal and informal, literally re-wires the brain. The more a person learns about something – a work task or a subject of interest – the more elaborate become the mental schemas that connect the various underlying concepts and principles. These schemas provide us with an understanding of how all the elements of a domain fit together and, as a result. enable us to solve problems and make decisions. After a while, we become so competent in a particular area that we seem to respond to situations intuitively, in other words without conscious thought.

All learning is a process of establishing patterns and making connections. When we know very little about a subject, we have very little prior knowledge to connect to. Without pre-existing schemas to build on, we need examples, stories, metaphors and similes to help us relate new information to our other life experiences. The novice craves a well-structured and supported programme of learning, which allows them plenty of time to process new information and to make sense of this in the context of practical application. They need reassurance and encouragement to help them through the difficulties they will inevitably encounter. In short, novices appreciate and benefit from good teaching and should, as a result, be the main focus of attention.

The more expert you already are in a particular area, the less structure and support you need to learn something new related to that area. We all have aspects of our life that we understand really well, whether or not we could easily explain what it is we know to someone else. We may be an expert in molecular biology, photography, accounting, office politics, bringing up children or the tactics of football. Because of our understanding, we can pretty well cope with any new information relating to our specialisms. We are very hard to overwhelm or overload, because we can easily relate new information to what we already know, to sort out the credible from the spurious and the important from the trivial. As an expert, we can cope with a long lecture, a densely-written text book, a forum with thousands of postings, or a whole heap of links returned in response to a search query.

These are the extremes. Of course there are many gradations of expertise and only a minority of learners are complete novices or acknowledged experts. But it is easy to see how, if we are not careful, we end up providing an ‘average’ learning experience which satisfies no-one.

We can over-teach those who already have a lot of expertise:

- We patronise them with over-simplified metaphors, examples and case studies.

- We frustrate them by holding back important information, which we then proceed to reveal on a careful step-by-step basis.

- We insult them by forcing them to undergo unnecessary assessments.

- We waste their time by forcing them to participate in collaborative activities with those who know much less than they do.

And we can under-teach the novices:

- We bombard them with information that they cannot hope to process, providing nowhere near enough time for consolidation.

- We provide insufficient examples and case studies to help them relate new information to their past experience.

- We are not always there when they get stuck or have questions.

- We do not go far enough in providing practical activities that will help them to turn interesting ideas into usable skills.

It may seem that I am suggesting you double your workload by providing two versions of each learning experience, but it doesn’t work like that. The relative experts need resources not courses and, of the two, resources are much easier to assemble. Many times you can just point the expert at the information and let them get on with it. And by doing this, you’ve reduced the population that requires a more formal learning experience considerably. You can start to give the novices the attention they deserve.

Next up: The motivation to learn

6. Every learner is different

![]()

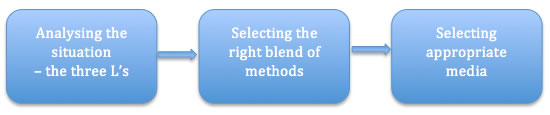

In postings 1-5, I outlined a simple process for designing blended solutions that are both efficient and effective: analysing the unique characteristics of the situation in which the solution is to be deployed; selecting the right blend of methods to meet the needs of the situation; and determining the delivery media best suited to these methods.

I started with the first step in the process – analysing the situation. This stage comes first because the information that we gather informs every one of our design decisions. I explained that situation analysis has three elements, which can be described quite simply as the three L’s – the learning, the learners and the logistics. Last week, I concentrated on the learning. This week I’m going to address learners and logistics.

Every learner is different

There’s a lot of talk in learning and development circles about learning styles, which are supposed to help teachers and designers of learning experiences to adapt their work to reflect the characteristics of different types of learners. This seems a reasonable endeavour until you reflect on the fact (I walked into that – because now I’m labelled a ‘reflector’) that there are literally hundreds of competitive models, which cannot, of course, all be right, and not one of these has come through any critical test of its validity.

The Association of Psychological Science concluded that: ‘There is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning-styles assessments into general educational practice.’ And in the UK, a review by The Learning and Skills Research Centre found the various theories ‘seriously wanting’ and with ‘serious deficiencies’. Many were downright dangerous as they ‘over-simplify, label and stereotype’. Donald Cark has reviewed this research in some detail in his blog Plan B.

The fact that we have yet to find a reliable way to categorise learners, does not reduce the need for a learner-centred approach to design or for empathetic teaching. As Dr John Medina makes clear in Brain Rules, every one of the world’s seven billion inhabitants is different:

“What you do in life physically changes what your brain looks like.”

“Our brains are so sensitive to external inputs that their physical wiring depends upon the culture in which they find themselves.”

“Learning results in physical changes to the brain and these changes are unique to each individual.”

Interesting as all this is, I’m not sure it takes us that far in terms of the big decisions we have to make when designing a blended solution. From my experience there are two learner characteristics that are far more influential than learning preferences. One is the extent of their prior learning, and the other is their motivation to learn about the subject in question.

Next up: The importance of prior learning

5. When the need is to shift attitudes

![]()

When I first entered the learning and development profession, I was assigned a mentor, a certain Mr Ernest Knagg. Ernest had strong opinions on just about all matters of pedagogy and good practice and that included the issue of attitudes. “Clive,” he said, “It’s not our business to try and change people’s attitudes. We can try and change what they do, but not what they feel about things.”

There’s a certain sense in what Ernest said, although time and time again I’ve encountered situations where attitudes are a major block to progress. I’ve checked this out with lots of other learning professionals and they agree. It’s almost impossible to address issues of knowledge and skill when attitudes are in the way.

An attitude is a predisposition, a tendency to think, feel or act in a certain way without reference to the facts of the situation. Try getting past “I absolutely hate computers”, “My job would be perfect if only there were no customers”, “I would never give a job to someone like that” or “E-learning is inherently evil.”

For a fuller discussion, see ‘A question of attitude‘.

Next up: 6. Every learner is different

4. When the need is for skills

![]()

Skills matter a great deal more at work than knowledge. Skills are the abilities to do things, to put knowledge into practice. As such, they directly impact on performance. There is really only one way to acquire skills and that is through practice, ideally with the aid of specific, timely and relevant feedback. If there is one consistent fault with the training programmes that most organisations provide, it is an over-emphasis on theoretical knowledge and a wholly inadequate provision for practice with feedback. By far the most successful training technique is to provide just the most essential information up-front and then to get the learner practising. You can feed in more ‘nice to know’ information as the learner begins to build confidence.

From the point of view of designing blended solutions, what really makes the most difference is to determine the type of skill that needs developing. To inform your choice of methods, it helps to make the distinction between rule-based tasks and principle-based tasks.

Rule-based tasks are algorithmic and repetitive. As long as you follow the rules, you’ll get the job done to a consistent quality. These are tasks like replacing a punctured tyre, completing a form or operating a cash register. You can teach these tasks using simple instruction – learn the rules, watch me doing it, then have a go yourself.

The trouble is that less and less of the tasks we have to perform at work are rule-based. After all, if they were that algorithmic, it would have been very tempting to get a robot or a computer to do them, or to move them off-shore. More of the work we do in the developed world is heuristic – it requires us to make judgements based on principles. Principles are not black and white – they need to be experienced rather than taught. As we shall see later, with principle-based tasks, we’re much better off using a strategy of guided discovery.

There is another way to analyse skills, which will help us when we come to make decisions about delivery media. This time we’re making a different distinction: when the learner applies this skill, with whom or with what will they be interacting?

Motor skills: In this case the learner is interacting with the physical world; for example, lifting a heavy object, driving a car, using a mouse. While these tasks can sometimes be simulated, as with flying a plane, more often than not we have to provide opportunities for practice with the real object in a realistic situation.

Interpersonal skills: Here the learner is interacting with people, as they would if they were making a sale, providing someone with feedback or making a presentation. Again, interpersonal tasks can be simulated, but no computer can accurately provide feedback on a learner’s performance. We’re going to have to provide opportunities for practice with other people.

Cognitive skills: In this case the learner is interacting with information. Lots of our tasks at work are like this, requiring us to solve problems and make decisions. Examples include business planning, using software, solving quadratic equations, writing reports, or reviewing financial data. Cognitive skills lend themselves more easily to computer-based practice.

Of course, you’re quite likely to find there’s a need for a mix of different skills – rule-based and principle-based, motor, interpersonal and cognitive. This is another powerful reason why blended learning can be so useful – there simply isn’t one method or medium that meets the whole need.

Next up: When the need is to shift attitudes

3. When the need is for knowledge and information

![]()

Knowledge and information are not quite the same thing. Knowledge is information that has been stored in memory, so it can be referenced without the need to refer to some external resource. This is an important distinction when you’re analysing requirements. It’s essential you find out what really needs to be remembered and what can be safely looked up as and when needed. There is a definite change in people’s expectations in this respect, because it has become so easy to search online on a PC or a mobile device that it seems pointless to try and remember all the information that’s relevant to your job. You’ll want to pick out those items of information that someone really must know if they are to perform effectively in their job. The rest you can provide as a resource.

Perhaps the greatest danger when analysing requirements is to over-estimate the amount of knowledge that people are going to need. The main culprits are subject experts who have long since forgotten what it’s like to be novices in their particular fields and think just about everything that they know will be interesting to learners and is important for them to know. A good way to resist this is to ask the question: “What’s the absolute minimum that learners need to know before they can start practising this task?” Again, this keeps the focus on performance.

Next up: When the need is for skills

2. Introducing the three L’s

![]()

I’m going to start with the first step in the process – analysing the situation. We do this first because the information we uncover at this stage underpins just about every decision we make when it comes to design. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that the most appropriate design can seem pretty obvious once you have the right information at your disposal.

Situation analysis has three elements, which can be described quite simply as the three L’s – the learning, the learners and the logistics. In the next few posts I’m going to concentrate on the learning. I’ll move on to handle learners and logistics.

By ‘the learning’ I mean the end point that we’re aiming towards with our solution. Be careful, because while learning may be our aim, our ‘client’ is probably much more concerned with what this learning might achieve in terms of increased performance. If we can focus in on performance, then this will serve us well when we come to making design decisions.

We cannot always take a requirement for a learning solution at face value. Our client may be wrongly diagnosing the problem. Work performance is influenced by objectives, organisation structure, available resources, working conditions, incentives and disincentives, aptitudes, motivation and the quality of feedback. None of these are going to be fixed through a learning intervention. Our job starts when there is a shortfall in knowledge (and information), skills and attitudes.

Next up: When the need is for knowledge and information

1. Getting started with blended solutions

![]()

The concept of blended learning may seem to you a little ‘old hat’ for 2013. After all, people have been blending learning methods and media for as long as there have been things people need to learn and others willing to teach them. Yet somehow, it is only in the last couple of years that the modern learning and development professional has fully comes to terms with the fact that a single approach – a classroom course, perhaps, or an e-learning module, or a period of on-job instruction – when used on its own, is rarely capable of completely satisfying a learning objective.

Blended learning is right now the strategy of choice for most major employers, whether or not that is how they describe it. The blended learning of 2013 is broad in scope, extending well beyond formal courses to include all sorts of online business communications, from webinars to videos. Increasingly, social and collaborative learning is also incorporated into the mix, as well as performance support materials, and opportunities for accelerated on-job learning.

Employers recognise that learning at work takes place continuously, whether or not it is formally planned. They understand that courses are not enough to change behaviour and increase performance. As a result, they increasingly expect more far-reaching solutions that go well beyond the presentation of information and half-hearted attempts at providing opportunities for practice. They want learning solutions that deliver and that places fresh demands on the designers of those solutions.

In this series of 20 short posts, I explore what I believe to be the most important elements in a systematic approach to the design of effective and efficient blended solutions: analysing the unique characteristics of the situation for which the solution is being designed; selecting the right blend of methods to meet the needs of the situation; and determining the delivery media best suited to those methods. This might sound abstract and theoretical, but stick with me, because the process can be quickly and easily applied in practice.

Next up: Introducing the three Ls