![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 3:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 3:

To quote Frank Felberbaum: “Each adult brain is endowed with approximately 100 billion neurons (nerve cells) – half of all the nerve cells in the body – but that’s just the starting point. From the moment we commence thinking, remembering, observing and learning, we are literally recreating our brains. Scientists have estimated that each of us has the capacity to make up to 10 trillion connections among our neurons, although most of us take advantage of only a small portion of this capacity. Each time we make a new connection we actually make ourselves smarter, not just because we know more, but because our brain actually works better.”

It’s time for a quick tour of the brain. Rising from the top of the spinal column is the brain stem, the oldest part of your brain, sometimes called the ‘reptilian brain’. The brain stem ‘remembers’ how to carry out the most basic functions necessary to keep us alive, regulating our breathing, heartbeat, sleep and waking.

Sitting on top of the brain stem is the limbic system, also known as the ‘old mammalian brain’. Here is where our emotions reside – all those survival-oriented feelings we need to keep the species going and to recognise danger and safety (although we may also have developed more sophisticated uses for our emotions). Here, too is the part of the brain that interprets sensory data, enabling us to respond quickly to danger.

The most uniquely human portions of our brain are the cerebellum and the cerebrum. When you’ve learned to do something so well that it becomes automatic – such as driving a car, riding a bike, typing or operating a computer – that memory, known as procedural memory (or sometimes ‘muscle memory’) is stored in your cerebellum, which sits just behind your brain stem.

The cerebrum consists of about two-thirds of our brain, which is where our personal memories are stored. The cerebrum is divided into two hemispheres, popularly known as the ‘left brain’ and the ‘right brain’. Although brain function is more fluid than these terms suggest, we can say generally that the left side of the brain handles logical thought, analysis, numbers and words, while the right side recognises patterns, perceives spatial relations and tends to think in images and symbols. Connecting the two hemispheres is the corpus callosum, which enables us to integrate these two modes of thinking. Research by Levy at the University of Chicago confirms that both sides of the brain are involved in nearly every human activity.

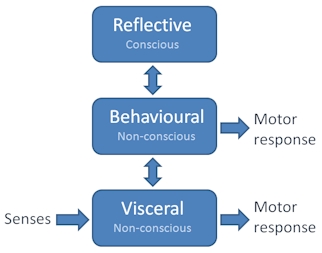

Thinking back to the three levels of brain function as described by Norman and colleagues, we can see that the visceral level can be localised to the limbic system, the behavioural level with the cerebellum and the reflective level with the two hemispheres of the cerebrum.

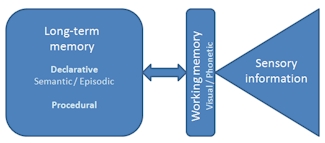

Felberbaum describes memory as “an active, dynamic process in which old and new information, associations and complex electrical circuitry all work together to synthesise everything we know into new responses.” Memory comes in a variety of forms. We’ve already heard about procedural memory, which records ‘how’ we do things. On the other hand, declarative memory (so-called because it can be articulated into words, i.e. it is conscious) is what we know about the world. It’s what we have learned as a result of simply living our lives or from more formal education and training.

Declarative memory can be divided into two sub-categories: semantic memory, which stores meanings, understandings, factual knowledge, concepts and vocabulary; and episodic memory, which stores information about particular episodes or events, including the time, place and associated emotions. Episodic memory and semantic memory are related. For example, semantic memory will tell you what a horse looks and sounds like. All episodic memories concerning horses will reference this single semantic representation of a horse and, likewise, all new experiences with horses will modify your single semantic representation of a horse.

Both declarative and procedural memories are long-term, but quite a bit of work has to be done for these memories to be formed in the first place. The brain is bombarded with sensory information but can actively pay attention to only a very small amount. This information is transferred to ‘short-term memory’, which allows a person to recall information for anything from several seconds to as long as a minute without rehearsal. Its capacity is also very limited: George A. Miller , when working at Bell Laboratories, conducted experiments showing that the store of short term memory was 7±2 items. More recent estimates show this capacity to be rather lower, typically in the order of 4-5 items. The limitations of short-term memory are significant because they explain how easy it is to overload a learner. The management of cognitive load is one of the most important responsibilities of the teacher or trainer.

Baddeley and Hitch, at the University of York, proposed a model of working memory, which seeks to explain how we integrate short-term memory with what we already know. Their model contains a ‘central executive’ working with two ‘slave systems’, one dealing with images and patterns, and the other sounds. Their work has helped to explain how it is that teachers can maximise their students’ capacity to learn by combining visual imagery with the spoken voice.

For learning to take place, new information entering working memory must be integrated into pre-existing mental models or ‘schemas’ in long-term memory. For this to happen, those schemas must also be transferred into working memory. As a result of rehearsal and elaboration, the incoming content is transformed to result in expanded schemas stored in long-term memory.

At this point, learning has almost taken place. The process is only concluded when the new schemas are brought back into working memory when needed to complete a task. Those schemas that incorporate cues that reflect the context in which the task has got to be performed are the most likely to be easily retrieved.

If this all sounds a bit complex and rather unnecessary, then don’t despair. Based on this knowledge of the brain and the research which this has spawned, cognitive scientists have been able to come up with a whole raft of practical guidelines for l&d professionals, guidelines that can be trusted and acted upon, allowing us to escape from the clutches of the quacks, the pop psychologists.

References

The Business of Memory by Frank Felberbaum, Rodale, 2005

Right brain, left brain: fact or fiction by Jerry Levy, Psychology Today, May 1985

The magical number seven, plus or minus two by George A Miller, in Psychological Review, 63, 1956

Coming next in chapter 3: Helping others to learn

Return to Chapter 1

Return to Chapter 2

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning screencasts: part 1

![]() A screencast is a demonstration of a task carried out in a software application or on a web site for use as a learning aid or for reference.

A screencast is a demonstration of a task carried out in a software application or on a web site for use as a learning aid or for reference.

To create a screencast, you simply carry out all the operations involved in completing the task and the software records this as an animation. This animation can be annotated with text labels, accompanied by an audio narration or both. Some authoring tools allow you to go beyond offering simple demonstrations, to provide the learner with opportunities to try out the tasks for themselves using a simulation of the original software.

This 3-part practical guide explores the potential for screencasting, describes the different types of tools available and provides some tips on how to make a good job of your own screencasts.

Media elements

A screencast contains one essential visual element – an animated software demonstration – supplemented by a verbal explanation, presented either as a series of pop-up text labels, an audio narration or as a combination of the two. Typically screencasts are presented as short, self-contained modules or in short sections, to make it easy for the learner to access the material in small chunks and often to practise as they go.

Interactive capability

Many screencasts are passive, presented as short videos which the learner can review quickly and then try out for real. Others incorporate simulations of software tasks which allow the learner to practise without having to leave the screencast and use the real application.

In their passive form, the most likely strategy for the use of screencasts is exploration, as material for use by learners at their own discretion, typically for reference. When simulated tasks are incorporated into the screencasts or when screencasts are combined with other activities that allow the learner to practise what they have learned, they can also play a key role in an instructional strategy.

Applications

Screencasts have two very obvious applications: they can be used as part of a formal training programme to introduce a new or revised software application or web site, or as reference material for people who are already users.

Screencasting tools

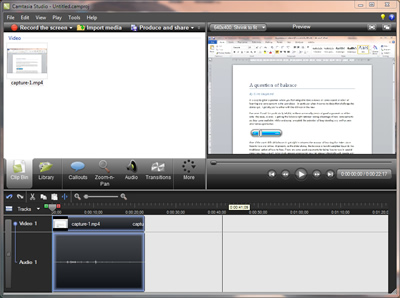

Some screencasting tools have been around for many years, long before the term ‘screencasting’ had been coined. These tools, like Techsmith Camtasia and Adobe Captivate, are desktop applications with sophisticated functionality. Over the years, their capabilities have been increased to support many forms of digital learning content, not just screencasts. These tools allow many ways for the learner to interact with the screencast and to undertake assessments. They also allow the author much greater control over the way in which the screencast is displayed.

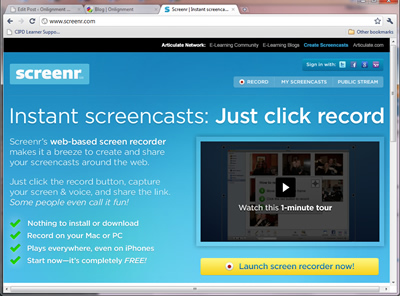

Other, much more recent tools, such as screenr and screenjelly, operate ‘in the cloud’. They allow you to create simple software demonstrations ‘all in one take’ and then to publish these online. In the next part of this guide we’ll be taking a much closer look at these online tools.

Coming next: creating all-in-one-take screencasts

Thanks to Craig Taylor for inspiring this guide with his session at the eLearning Network event on April 8th.

A little reflection does us good

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the second part of chapter 3:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the second part of chapter 3:

We go to work to do things, not to learn. Depending on how we earn our living, what this doing actually entails may be little more than repeatedly drawing upon our repertoire of learned behaviours – we’re literally on auto-pilot. More commonly, we’re also having to work at the reflective level, to analyse problems, come up with solutions, communicate with others and make decisions. Now in the process of doing all this, our behaviours will inevitably adapt and evolve to some extent with no conscious effort on our part – we learn through simple trial and error, and by our observations of the successes and failures of others. But this is a haphazard and uncontrolled way to proceed if you value your job and your career – there’s a definite risk that, regardless of the number of years that you clock up, you’ll have the same year’s experience over and over again.

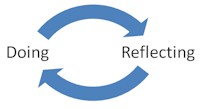

So, at very least, we need our learning model to extend beyond doing:

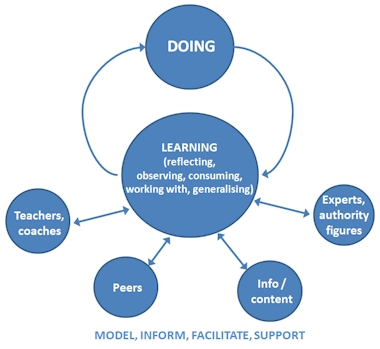

Left to our own devices we can do quite well, thank you. But imagine how much richer our learning could become if we were able to draw upon the resources of others, who have attempted the same tasks in the past. As we look further afield for assistance, our learning model becomes correspondingly more complex:

- As we develop our network to include experts and peers, and gain access to prepared content, such as reference materials, we have the basis for just-in-time learning – learning at the point of need.

- As we extend our network to include coaches, mentors, on-job instructors and professional colleagues, and as we gain access to all manner of learning materials, we can start to get ahead of the game, to develop our knowledge and skills to meet future challenges.

- And as we build further relationships with teachers, trainers, facilitators and co-learners, we have the opportunity to formalise our learning outcomes through educational and training courses.

The people and content with whom we interact perform many useful functions:

- They model effective behaviour.

- They inform us of the facts, concepts, rules, principles, procedures and processes that underpin effective behaviour.

- They facilitate our learning by encouraging us to participate in thought-provoking and challenging activities, by introducing us to useful resources, and perhaps most importantly, by asking the right questions.

- They support and encourage us by establishing the right emotional conditions for learning and helping us out when we’re in difficulty.

Which leaves us to observe, to reflect, to consume all that content which we find for ourselves or which we are pointed towards, to work with new ideas, and to generalise about what we should do in the future. Now we’re motoring.

Coming next in chapter 3: Taking a look beneath the hood

Return to Chapter 1

Return to Chapter 2

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning slide shows: part 4 – distribution

![]() In the first part of this practical guide, we discussed the potential of stand-alone slide presentations as a tool for learning. We moved on to look at the visual element in the presentation – the slides – and the auditory component – the narration. In this final section, we explore what’s involved in getting your slide show out there in front of as many eyeballs as possible.

In the first part of this practical guide, we discussed the potential of stand-alone slide presentations as a tool for learning. We moved on to look at the visual element in the presentation – the slides – and the auditory component – the narration. In this final section, we explore what’s involved in getting your slide show out there in front of as many eyeballs as possible.

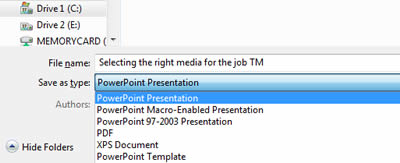

Keeping it simple

Your first option is to send round your presentation in its native PowerPoint format or to make this available for download. This will work as long as everyone who is likely to want to view the slides has their own copy of PowerPoint and are able to view the slides in the format in which you have saved them (for example, to view presentations saved in the pptx format, viewers must have PowerPoint 2007 or later). Presentations saved in native PowerPoint format will be bulky but they can still be edited by the recipient (if you regard that as an advantage).

A simple alternative is to save your slides directly from PowerPoint into PDF format. This reduces compatibility problems as most people have a PDF reader. It will also reduce file size. However, the files will no longer be editable.

Converting to Flash

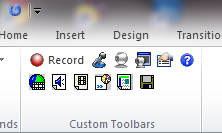

You can achieve a more polished and web-friendly result using one of a number of tools that will convert your presentation into Flash format, along with a host of useful additional features. Perhaps the best-known of these tools are Articulate Presenter and Adobe Presenter (although you might also take a look at the newly-released and budget priced Snap! by Lectora). These work similarly in that they sit within PowerPoint itself as an add-in, with their own ribbons or drop-down menus (depending on the version of PowerPoint).

Using these tools you can add narration, organise your slides into sections and sub-sections, insert additional media such as Flash animations and videos, and then publish into Flash for upload to your intranet, learning management system or other web site. Actually these tools can do a lot more in terms of adding interactivity, but that goes beyond the scope of this practical guide.

Exporting to video

If you just want your slides to be viewed in a linear fashion, from start to finish, and you are prepared to add an audio narration, then you should seriously consider distributing in video format. One attraction is the ease with which you can upload video to sites such as YouTube. Another is the fact that nearly all mobile devices will support video, whereas Flash can be a problem, particularly on Apple devices.

You need a tool which will capture your slides, allow you to add narration and then publish to a suitable video format. If you are happy to go with the Windows Media Video (WMV) format, then you can do this directly from the latest version of PowerPoint. If you want a bigger choice of formats and more editing flexibility, try using a tool like Camtasia.

Once you have captured your slides (including any embedded animations and videos), the Camtasia Studio software allows you to make edits and export to a wide range of video formats.

Publish on SlideShare.net

Another option to consider, if you want your presentations to have the widest possible online presence, is to publish to a site like SlideShare.net. What YouTube is to videos and Flickr is to photos, SlideShare is to presentations.

The process is really simple. You set up an account and then upload your PowerPoint or Keynote slides, which are then automatically converted into SlideShare’s Flash-based format. Users can view and comment on the slides on the SlideShare site or you can embed the slides in a web page or posting.

That concludes this practical guide.

A PDF version will be available for download soon.

Learning = adaptation

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 3:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 3:

As human beings we must learn if we are to ensure our survival, to adapt to the ever-changing threats and opportunities with which we are confronted. As a result we are born as learning machines, capable of great achievements with or without the help of others.

Of course, we do start off with some basic, but still absolutely essential capabilities. At an instinctive, ‘visceral’ level, we are hard-wired to react positively to situations that, throughout our evolutionary history, have provided us with the promise of food, warmth or protection. Similarly, we are predisposed to respond negatively to those situations which have historically represented danger. These responses, positive or negative, are emotional ones, alerting the rest of the brain and sending signals to the muscles.

Beyond this rather primitive level, the brain is also capable of acquiring and then applying all sorts of skills and behaviours needed to function effectively in the world. Some of these are so important, they are set up in advance. As Norman describes : “The human brain comes ready for language: the architecture of the brain, the way the different components are structured and interact, constrains the very nature of language. Moreover the learning is automatic: we may have to go to school to learn to read and write, but not to listen and speak.”

Once these behaviours are firmly established through repetition, the brain is quite capable of carrying them out routinely without any conscious effort. There are literally thousands of things that all humans can do without trying, without giving a second thought; a state that some educationalists have referred to as ‘unconscious competence’.

According to Norman, Ortony and Russell, psychologists at Northwestern University, the brain operates at three levels. The first two, the visceral and the behavioural, are sub-conscious, as we have seen. The third is of a higher order. It allows us to reflect on our experiences and communicate these reflections to others. And because the lower level functions look after themselves, we can do all this while we carry out all sorts of everyday behaviours, the one sense in which we can genuinely multi-task.

Just as the behavioural level of the brain can enhance and inhibit our responses at the visceral level (so we don’t have to run and hide if we encounter a spider, and so we can develop a taste for bitter tasting food and drink if that’s what we like), the reflective level can enhance or inhibit our behaviours, so we can improve our performance or react to change. As an aside, the reflective level can also get in the way of performance, as tennis or golf players will attest when their inner voice berates them for their shortcomings and questions their ability to perform shots that have long since been assimilated into ‘muscle memory’. Timothy Gallwey has done very well with his Inner Game books, persuading players to ignore their reflective minds and ‘just do it’.

Well life isn’t just a game of tennis (more’s the pity). We need our reflective minds to investigate, question, contemplate and generalise. That’s what makes us human. That’s how we grow and adapt. As Jay Cross concludes, “Learning = adaptation. The strength of the human mind … is its ability to adapt to a change in circumstances. We call this learning.”

References:

Emotional Design by Donald A Norman, Basic Books, 2004

The Inner Game of Tennis by Timothy Gallwey, Jonathan Cape, 1975

Coming next in chapter 3: A little reflection does us good

Return to Chapter 1

Return to Chapter 2

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning slide shows: part 3 – the narration

![]() In the first part of this practical guide, we discussed the potential of stand-alone slide presentations as a tool for learning. In the second installment, we looked at the visual element in the presentation – the slides. This time we look at the auditory component – the narration.

In the first part of this practical guide, we discussed the potential of stand-alone slide presentations as a tool for learning. In the second installment, we looked at the visual element in the presentation – the slides. This time we look at the auditory component – the narration.

Packaging up a live presentation

The way you approach the narration will depend on whether you are (1) packaging up a presentation that you have previously delivered live, or (2) creating a stand-alone slide show from scratch. In the case of the former, the presentation will most likely represent you and your perspective on the topic in hand – you will want to record the voiceover yourself and retain as much of the personality of the original presentation as possible. That means keeping it natural and informal. Assuming you didn’t read from a script when you presented live (and let’s hope that’s the case), then you won’t want to read from a script now. Try to capture the buzz of the live presentation by imagining you are presenting to a live audience. Or why not record it live? You can always edit it down afterwards to remove any superfluous elements.

Designing specifically for stand-alone use

On the other hand, you may be designing a slide show that will only ever be used as a piece of learning content. It is not intended as a personal statement and it won’t be attributed to you. In this case you are almost definitely best off writing a script and you should seriously consider using a professional voiceover artist to deliver this. Why? Because professional voiceover artists are very good at reading a script so it doesn’t sound like they’re reading a script. By and large, the rest of us aren’t.

Script for speaking

When scripting, it’s hard to avoid slipping into report writing mode. Keep reminding yourself that the words you are writing will be read aloud, not read from the screen. Try saying the words out loud yourself and keep revising them until you can put them across effortlessly.

Use a conversational tone

Whatever you do, avoid ‘corporate drone’. Write as you would speak. That means short sentences, simple language, the active voice (“The cat ate the mouse” not “The mouse was eaten by the cat”), and a free use of contractions (“I can’t remember …” not “I cannot remember …”). You can also help the voiceover artist by making absolutely clear (perhaps in bold type) which words need special emphasis.

Don’t duplicate your voiceover as on-screen text

Your learner’s brain can cope with one verbal channel (in this case the voiceover) but not two. If words are coming at you from two places at once, you’ll just overload. If absolutely necessary, emphasise key points and headings with on-screen text, but please don’t display your script verbatim.

Coming next: distribution

A parade of bandwagons

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth and final part of chapter 2:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth and final part of chapter 2:

In finding ways to meet these new challenges and take advantage of new opportunities, it sometimes seems that l&d professionals are pushed from pillar to post. They are confronted by a dazzling and never-ending parade of bandwagons, each trumpeting their over-hyped claims and each damning their predecessors as out-dated and ineffective. Here are just a few of the unnecessary face-offs we’ve had to endure:

off-job v on-job learning

the classroom v e-learning

just-in-case v just-in-time learning

instruction v discovery learning

formal v informal learning

In each case, the implication is that there must be a winner and a loser; one is right and one is wrong. The falsity of this position is a fundamental cornerstone for this book. We don’t want to see any more babies (some of which to be honest are actually quite grown-up by now) thrown out with the proverbial bathwater. The 21st century l&d professional needs to be able to integrate all these possibilities, in the right proportions to meet their learning requirements, the needs of their audiences, within their particular constraints and taking advantage of their particular opportunities. They cannot achieve this if they are swinging wildly from one extreme position to another, trying one potential panacea for a little while and then moving on to another.

Training has for too long endured the unnecessary battle between the rationalists and the romantics, the ‘left brainers’ and the ‘right brainers’. Each camp is firmly entrenched in their positions, too busy ‘sneer leading’ to try and see the world from the perspective of their so-called enemy. Change will not be brought about by overcoming the enemy, nor by negotiating a ceasefire. It will come when we recognise those with differing views as the colleagues they undoubtedly are, doing their best just like you to make things work in difficult circumstances. Trainers shouldn’t just preach diversity, they should practise it too.

It’s time for some whole brain thinking. Less new-age voodoo. Less analysis paralysis. More learning and development.

Meanwhile, learners certainly have no doubt that changes are in the offing as the SkillSoft survey clearly demonstrates: “Traditional classroom training doesn’t have a large presence in the future according to those employees surveyed. Only 16.2% expected to be learning in a traditional classroom environment at an off-site location and only 33.4% expected classroom courses in the workplace to continue.”

But there is some scepticism that this change will be brought about by the old guard of the l&d profession, the dinosaurs. There are parallels in other fields, as Max Planck suggests, “An important scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning over and converting its opponents. It rarely happens that Saul becomes Paul. What does happen is its opponents gradually die out and the growing generation is familiarised with the idea from the beginning.”

I’m much more optimistic. It is natural for people – and that includes trainers, of any age – to resist change if this is thrust upon them. But they will engage wholeheartedly if they understand why change is necessary and if they are part of the solution. The alternative is not an attractive one, as Jack Welch points out: “When the rate of change outside exceeds the rate of change inside, the end is in sight.”

References:

The Future of Learning, SkillSoft, 2007.

Great Thoughts About Physics by Max Planck, 2006, quoted in Knowing Knowledge by George Siemens.

That concludes chapter 2. We move on to chapter 3: Part 1: Learning=Adaptation

Return to Chapter 1

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning slide shows: part 2 – the slides

![]() In the first part of this practical guide, we reviewed the capabilities of, and applications for, packaged slide presentations as a tool for learning. In this second installment, we look in more detail at the visual element in the presentation – the slides. Next time we’ll examine the best ways to go about recording a narration.

In the first part of this practical guide, we reviewed the capabilities of, and applications for, packaged slide presentations as a tool for learning. In this second installment, we look in more detail at the visual element in the presentation – the slides. Next time we’ll examine the best ways to go about recording a narration.

What your slides must achieve

If your slide show is going to be packaged with an audio narration, then your slides have very much the same function as they would do in a live presentation – they convey the visual element, while a voice delivers the words. In this context, slides are visual aids. With photographs, illustrations, diagrams and charts, they capture the viewer’s attention, clarify meaning and improve retention. With the sparing use of on-screen text, they can also help to reinforce key elements of the verbal content, but the prime purpose is always visual.

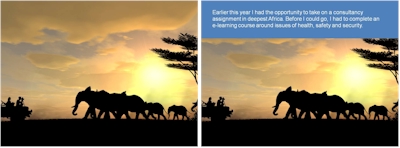

Without narration, your slides have to accomplish both roles – the visual and the verbal. In this respect they need a very different design focus to a live presentation. Take the following example of a slide taken from a live presentation that was converted to stand alone, without narration, on slideshare.net. A section of the slide has been allocated to a running textual commentary, essentially a much simplified version of the original presenter’s words:

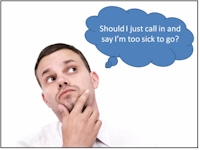

Not that this is the only way of displaying the verbal content. If, rather than converting a live presentation, you were designing a stand-alone and un-narrated slide show from scratch, you could use all sorts of devices to display the words, like the speech bubbles used in this example:

Another consideration is the distance from which your slides will be viewed. In a live presentation, your audience is likely to be some way from the screen, whereas when the slides are used for self-study, they will be up close. Whether this matters depends on the device the audience will be using to view the presentation (this could be anything from a smart phone to a large PC monitor) and the size of the window in which your presentation will be displayed. You may be able to get away with displaying more detail than you would when live, but this needs testing.

An argument for imagery

Only an expert wordsmith can conjure up with words what a person, object or event actually looks like. Only an expert teacher can explain a concept or process clearly using words alone. And only a wonderful presenter can make a lasting impact on an audience without the use of imagery. As the saying goes, “a picture is worth ten thousand words”. Pictures show, quite effortlessly, what things really look like. They clarify concepts and processes. They stick in the memory. All you have to do is use them.

Pictures come in a variety of forms to suit different situations. Photographs portray what things look like; diagrams clarify concepts and processes; illustrations make the abstract more memorable. Presentation software such as PowerPoint makes it easy to employ pictures in all these forms. Your task is to avoid the lazy option – clip art – and to find the picture that really does tell a story.

Break the mould

It’s all too simple to use the standard templates provided by your presentation software, but these won’t always do justice to your images. Take these two examples:

You can definitely do without the slide junk – the logos, headers and footers that appear on every slide. There’s a place for your logo and that’s on the title slide (OK and maybe at the end as well). And you don’t really need all that clutter at the bottom of each slide – you’re producing slides, remember, not a report.

Text is also OK in moderation

You’ve probably heard of the expression “death by PowerPoint”. You’ve probably experienced it.

Yes, we’ve all been there, and yet we put up with it – see The Emperor’s New Slide Show.

Well, by far the biggest complaint you will hear from presentation audiences is that the slides contain too much text. In his book The Great Presentation Scandal, John Townsend relates how he counted the number of words and figures on every slide at a conference he was attending. The overall average was 76. That’s right, 76.

Given this, you may find it surprising that we could be recommending the use of text as a visual aid when the real problem is that there’s far too much of it. This is a fair point, but text can be useful as a visual aid, when you need to highlight the start of a new section, emphasise a key point, list a number of related points or present data in the form of a table.

If you do keep the amount of text on your slides to a minimum, it will have that much more impact when it does appear; particularly if you know when to use it and how to lay it out like the professionals. If you obey a few simple guidelines, that’s what you will achieve.

Use your slides to tell a story

A presentation is much more than a collection of independent thoughts accompanied by visual aids – however interesting the thoughts and however brilliant the visuals. Just like a novel, a radio play or a film, it has a beginning, an end and a carefully planned route in between.

Too many presentations look like they have been constructed by simply extracting slides from previous presentations. Although re-using slides is fine, if they are appropriate to the task in hand, this is never going to be enough to do the job. Like a film director, you have to look at the big picture, using words and images to manipulate your audience’s attention and their emotions. There is no black art to this; you just need a little imagination and a simple structure.

Coming next: the narration

Have the opportunities and constraints changed?

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 2:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 2:

Let’s start with the constraints and there are plenty. For a start, organisations are demanding ever faster response from the l&d department. According to Bersin & Associates (2005), “a whopping 72% of all training challenges are time critical.” Some 38% of trainers surveyed in the USA by the eLearning Guild (2005) indicated that they were under significant pressure to develop e-learning more rapidly. A further 40% were under moderate pressure. The demand is felt most acutely for product training and technology training – subjects where timeliness is most critical and the content is most likely to change.

The pressure is also being felt because of increased regulatory demands. According to the Law Society of Scotland (2007): “UK employment law has moved far and fast since 1997. No other field of law has been the subject of such an ambitious, relentless and far-reaching legislative programme.” To meet legal requirements and reduce the risk of costly claims for compensation, compliance training is utilising a high proportion of training capacity.

And trainers will have to meet these demands with less budget. According to the CIPD’s 2009 Learning and Development Survey – which questioned 859 learning, training and development managers – annual spend per employee on training was down by about a quarter, from £300 to £220. Time will be as stretched as budgets, with flatter structures, less central bureaucracy and increased outsourcing.

Trainers aren’t the only ones short of time. According to an article in Business Week quoted by Jay Cross, “a third of all knowledge workers clock more than 50 hours a week, 43% get less than seven hours of sleep a night, 60% rush through meals, and 25% of executives report that their communications are unmanageable.” And in the SkillSoft survey4, “40% of those surveyed said they didn’t have time to do the training they needed.”

At the same time, there are some wonderful opportunities, not least because of the World Wide Web. As Kevin Kelly reported back in 2005, “In fewer than 4000 days we have encoded half a trillion versions of our collective story and put them in front of one billion people, or one-sixth of the world’s population. That remarkable achievement was not in anyone’s 10-year plan. Ten years ago, anyone silly enough to trumpet the above as a vision of the near future would have been confronted by the evidence: there wasn’t enough money in all the investment firms in the entire world to fund such a cornucopia. The success of the Web at this scale was impossible.” To help us take advantage of the Web, we are seeing a much improved technical infrastructure, with broadband connections increasingly available inside and outside of the firewall.

The rise in internet usage is topped only by the phenomenal growth in the use of mobile phones (there are currently some 4.5 billion users – one half of the world population) and other hand-held devices, such as games machines and portable MP3 players. As these devices continue to acquire increased power, functionality and bandwidth, the opportunities for l&d become self-evident.

References:

Informal Learning by Jay Cross, Pfeiffer, 2006.

The Future of Learning, SkillSoft, 2007.

Kevin Kelly in Wired Magazine, August 2005.

Coming next in chapter 2: A parade of bandwagons

Return to Chapter 1

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

The Emperor's New Slide Show

Once upon a time there lived a vain Emperor whose only worry in life was to impress his subjects with the extraordinary quality of his business presentations. He developed new slide shows almost every day and loved to show them off to his people.

Word of the Emperor’s tremendous presentations spread over his kingdom and beyond. Two scoundrels, named Bill and Bob, who had heard of the Emperor’s vanity, decided to take advantage of it. They introduced themselves at the gates of the palace with a scheme in mind.

“We are two very good software designers and after many years of research we have invented an extraordinary method for the creation of visual aids that is so advanced and automated in its design that it almost completely eliminates the need for any serious creative effort on your part, thus allowing you to develop more presentations more quickly than ever before. As a matter of fact, we have streamlined this system to such an extent that most of your slides will look just like text to anyone who is too stupid and incompetent to appreciate their quality.”

The chief of the guards heard the scoundrels’ strange story and sent for the court chamberlain. The chamberlain notified the prime minister, who ran to the Emperor and disclosed the incredible news. The Emperor’s curiosity got the better of him and he decided to see the two scoundrels.

“Besides being almost entirely text, your Highness, these slides will have a uniformity of style and design that will make almost every slide look exactly the same, reinforcing your imperial branding. And there are other benefits too. Rather than having to rehearse your presentation, you will be able to read your notes right off the screen. And no more wasted hours developing handouts – simply print out your slides and all the words will be there.” The emperor gave the two men a bag of gold coins in exchange for a multi-site license to use the remarkable new software in all of the Emperor’s many residences and offices.

The Emperor set to work on his first presentation. Amazingly, just as Bill and Bob had promised, he was able to put together his slides in a matter of minutes. He called the Prime Minister in for a preview. “That’s strange, ” thought the PM. “All I can see is slide after slide of bullet points, presented in a mind-numbingly uniform imperial branding. Where are all the photos, the diagrams, the charts and the video clips that made the Emperor’s presentations so famous?”

But before querying this with the Emperor, he thought again: “If all I see is text, then that means I’m stupid! Or, worse, incompetent!” If the prime minister admitted that he could only see text, he would be discharged from his office.”

What a marvellous slide show, Emperor,” he lied. “So minimalist, so … so consistent.” Encouraged by this positive response, the Emperor set about using his new software to develop presentations at such a rate that soon almost all the government’s time was spent in attending them. No-one could criticise the monotonous nature of the Emperor’s slide shows without being accused of stupidity and risking their job. Exacerbating the situation, The Emperor ordered all his officials to develop presentations of their own to provide him with daily updates on matters of state.

One day, a schoolchild on a job placement scheme was invited to sit in on one of the Emperor’s presentations. Bored silly by the slides and aware that most of the audience was losing consciousness, he couldn’t help but remark to those around him: “These slides are just text. They’re not visual aids at all. In fact, this presentation’s a load of xxxx.”

“Fool!” his supervisor snapped. “Don’t talk nonsense!” He grabbed the child and took him away. But the boy’s remark, which had been heard by practically everyone except, luckily, the Emperor, who was too busy reading his script from the screen, was repeated over and over again until everyone cried: “He’s right, you know, it is just text. There are no real visuals and this presentation’s just a load of xxxx.”

And you know what? They were right.

The Emperor’s New Slide Show is extracted from the award-winning 2003 CD-ROM Ten Ways to Avoid Death by PowerPoint. The wonderful pictures are from David Kori.