![]() In part 1 of this series, we looked at what a learning scenario is, its basic structure, capabilities and applications. We move on now to look in more detail at the steps involved in creating simple scenarios to support learners in understanding the principles underlying everyday problem-solving and decision making. Scenarios are well suited to this type of learning problem, because they provide learners with the opportunity to experiment with different responses to the sorts of situations that they could encounter in their jobs and to gain insights into the dynamics which can determine success and failure.

In part 1 of this series, we looked at what a learning scenario is, its basic structure, capabilities and applications. We move on now to look in more detail at the steps involved in creating simple scenarios to support learners in understanding the principles underlying everyday problem-solving and decision making. Scenarios are well suited to this type of learning problem, because they provide learners with the opportunity to experiment with different responses to the sorts of situations that they could encounter in their jobs and to gain insights into the dynamics which can determine success and failure.

When we talk about ‘principle-based tasks’ we mean those jobs that cannot be accomplished by following simple rules – ‘if this happens then do that’. Principle-based tasks require you to make judgements on the basis of the particular situation you happen to be facing. They require you to understand cause and effect relationships, i.e. principles:

- Projects with unclear objectives are more likely to fail.

- Irritable behaviour can be caused by lack of sleep.

- You’ll find it easier to cope if you don’t look at each email as soon as it comes in.

- An impolite greeting will turn the customer against you before you’ve begun.

Principles such as these are relevant to just about any job you can imagine, although clearly some more than others. They are rarely black and white – in fact they are often the subject of differing opinion. Principle-based tasks, therefore, require a very different treatment and this is where scenarios come into their own.

Step 1: Decide what principles you want to bring out through the scenario

A scenario needs a clear purpose – don’t use it just to lighten up what would otherwise be a boring piece of e-learning. Be realistic about what you can achieve in one scenario. You may be able to tackle a simple principle with a single question, but often a whole series of questions will be required to bring out all the elements and to compare different perspectives. A lot depends on your learner. Novices will want to look at a single issue at a time, whereas more experienced practitioners may feel comfortable immersing themselves in a complex situation with all sorts of competing pressures. If in doubt, keep it short and simple.

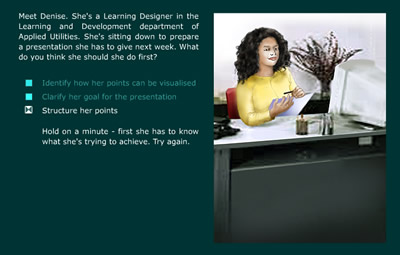

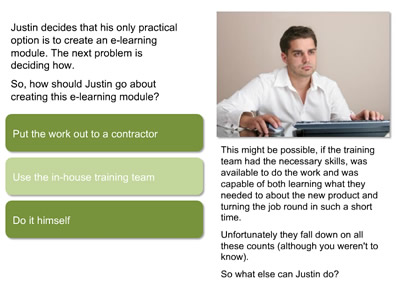

Step 2: Develop a storyline

Your next task is to develop a storyline that will bring out the principles you have chosen to focus on. It is really important that this storyline is credible with your audience. They must be able to relate to the situation and the characters. If you are struggling for ideas, ask a sample of your potential learners to describe the situations they face in their own day-to-day work. As with TV drama, be careful not to base your plot too closely on a real-life incident in case you reveal the identity of the protagonists.

The problems that you set should be challenging yet achievable. Remember that what is challenging for a beginner may be completely obvious to an old hand, so adapt your scenario to your audience. With beginners, it’s a good idea to start with relatively straightforward and routine problems, and move gradually to the more complex cases in which right and wrong is not so easy to establish.

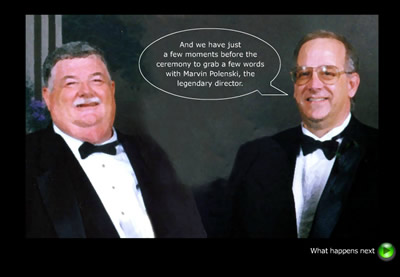

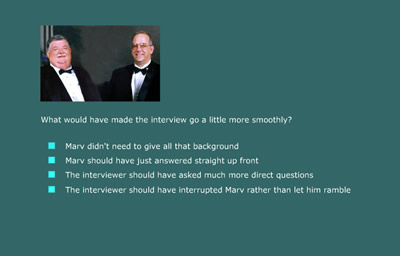

Step 3: Develop your script

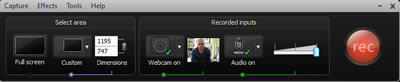

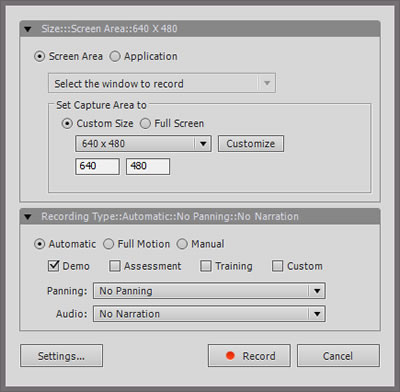

Use whatever media are necessary to convey the storyline. More often than not text will do the trick, but some situations will be hard to get across without richer media.

Without doubt, your hardest job will be to develop plausible options for your questions. Every option should be tempting to at least a minority of your target audience. Throwaway options, which are clearly not going to work, will devalue the whole process.

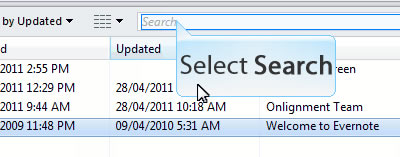

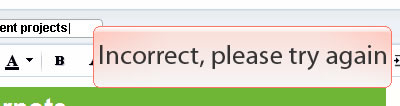

Assuming this is not a branching scenario (and we’ll be dealing with these later in the series), every option should have its own feedback. Writing this feedback will not be as simple as “Correct – well done” or “Sorry, incorrect.” Every answer deserves a considered response, weighing up all the pros and cons. If the feedback won’t fit on the same screen as the question, jump to a new screen where you have more room. Remember that this feedback will be the primary source of new learning, so it shouldn’t be wasted.

Again, assuming you are not creating a branching scenario, you should allow the learner to explore any and all of the options before moving on. A scenario is not an assessment, so don’t follow assessment rules.

Step 4: Test and revise then do it again

You’ve probably got the message by now that a scenario needs to be authentic. The only way you will tell whether you’ve got this right is to try it out with typical learners. Bring them in early. Have them provide a verbal commentary to you as they attempt the questions. Act on their feedback and then test again. You are not admitting a mistake by changing your script – you are showing how much you want to make it work.

Coming in part 3: creating simple scenarios for rule-based tasks