![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the eighth and final part of chapter 4:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the eighth and final part of chapter 4:

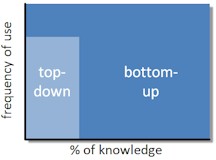

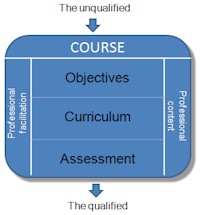

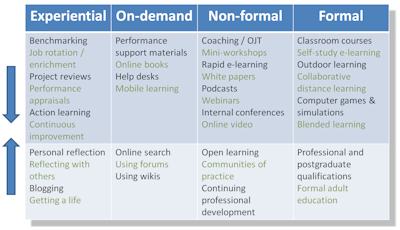

A multitude of opportunities for increasing learning exists within every context, both from the top down and bottom up. The table above shows just a sample of what is available. Some of these opportunities are certainly not new, but may not have been fully exploited in the past. Others – such as blogging, electronic performance support, online books, mobile learning, using forums and wikis, online search, podcasts and webcasts, social networking and blended learning – have resulted from relatively recent technological developments, and have certainly not yet been used to their full potential.

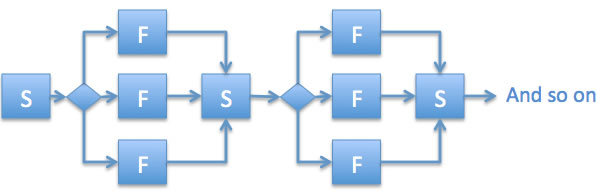

The model can help l&d professionals to:

- consider all the contexts in which learning can take place at work and the opportunities that exist in each of these contexts;

- assess the relative priorities that should be placed on each of the four contexts for a given population;

- provide the right balance of top-down and bottom-up learning for that population;

- create the conditions in which this strategy can succeed.

This process needs to be informed by a thorough understanding of (1) the role that each context plays in an overall l&d strategy, (2) the conditions necessary for learning to thrive from both the top-down and the bottom up, and (3) the range of opportunities that exists to support learning in each case. Much of the rest of this book is devoted to ensuring that understanding.

In the meantime you may be overwhelmed by the abundance of options at your disposal. There’s no doubt that learning and development was a lot simpler when it consisted either of sitting next to Nellie or attending a class. I remember George Siemens once saying that the more choice we have, the more likely we are to choose the familiar option. If that’s the case we’re all doomed. We have waited a long time for the tools to arrive. Now they’re here, the least we can do is try our best to put them to work.

Coming next, the first part of chapter 5: The scope of top-down learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect