I’ve been experimenting with a fun library of PowerPoint artwork and templates called Doodleslide. It comes in the form of a plug-in for PowerPoint or Word on Office 2003-2010 (PC only, not Mac). If you use Doodleslide artwork throughout a presentation, it will certainly break the mould. It could work just as well for PowerPoint-based e-learning if that’s what you do.

I know it won’t work for every situation, but it will for some, and that’s worth the $49.95. You’d have to be careful mixing it with other styles of artwork, of course, to avoid producing something completely mad, but I’m sure it’s possible. Worth a look.

Working with subject experts 3 – asking the right questions

There are plenty of ways of getting the information you need. The worst way is to get the SME to produce a PowerPoint deck. What you will get is far too much information, expressed almost entirely in bullet points. The SME will be aware that this isn’t the finished article, but expects that somehow you will weave your magic by adding a load of pictures and other decorations, and sticking a quiz on the end. But you’re not going to do that, are you?

Every slide, no every bullet, that you remove from the SME’s slide deck will involve intense negotiations. The SME will be in mourning for ages afterwards, if indeed they ever recover. Better to avoid this process altogether.

One way to research the topic is to sit in on an existing class, perhaps one for which the SME is the instructor. Talk to participants to see what they found useful and what they found confusing. Extract the important learning points, but even more importantly, note down all the instructor’s war stories, examples, anecdotes and jokes. All too often, the reason why learning content is so dull is because it is so matter of fact – it has no personality. The stories are a lot more than entertainment. They provide context and relevance. They allow learners to see patterns and make connections, which is what learning is really all about.

Chances are you’ll also need to interview the SME. Documents and slide decks are OK up to a point but they are a long way from where you want to be. Your focus is on the performance. What do you want the learner to be able to do? What activities can you devise that will allow them to practise doing this? What knowledge does the learner need in order to engage in this activity? Credit is due here to Cathy Moore who spells out the questions to ask as part of the process she calls Action Mapping.

If your SME has only ever experienced knowledge dumps then you may have difficulty communicating what it is that you are aiming to achieve. The best way to overcome this barrier is to show the SME the best example you can find of performance-focused learning content. If you can’t find anything, perhaps you need to create some demo material yourself.

Unless you are really lucky (or skilful), the SME will still want to include more material than you believe is really appropriate. This is the point to make the distinction between courses and resources. The aim of the course is to engage the learner’s interest in the topic and help them to develop sufficient confidence to move forward independently. That is not the end of the story. Learning will continue back on the job and learners will inevitably have many questions of detail, which is where the resources come in, available online, on-demand. Resources are not an optional extra; they are step 2 in the plan. All the information that the SME recommends will be included; it’s just that most of it will be at step 2.

Finally, don’t forget to thank the SME for all their hard work. Even better, credit them on the materials. They will appreciate it.

Part 1 Part 2

Coming in part 4: What when you are the SME?

First published in Inside Learning Technologies, November 2011

Live online learning doesn't have to mean wearing headphones

I know some people spend half their lives with headphones on, but I find even my cushioned, noise-cancelling kit from Bose gets tiring after a while. For Skype and web conferencing I’d love to free myself from using a headset if I could, without losing audio quality or suffering from echoes.

So I was keen to have a play with this equipment from Phoenix Audio Technologies, designed to allow one or more participants to communicate clearly online without having to be up-close to a microphone. It does some whizzy echo cancellation and noise reduction, so even in a busy environment you should be able to come over clearly.

So what applications do these devices have for online learning and communications?

- Use the Duet instead of a headset when you’re on Skype or web conferencing.

- Use the Quattro when you want to include a whole room full of people in a web conferencing session.

- Use the Duet or Quattro as a way to record interviews and discussions for podcasts and videos. Although the Quattro has four microphones, it only provides a mono signal, but that may not matter to you. The sampling rate is a maximum of 16 KHz, which is not brilliant, but this is likely to be fine for everyday online playback. For recording an individual voice, perhaps to narrate a slide show or screencast, you will definitely get better results from a specialist USB condenser microphone such as the Yeti.

Media for formal learning

![]()

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the seventh part of chapter 7:

In contrast to educational and training methods, the options in terms of learning media are growing exponentially. If methods have the main impact on the effectiveness of a learning intervention, then media have the main influence on efficiency – the way in which resources are used to deliver the learning outcomes. The possibilities for efficiencies have grown enormously with advances in technology.

Not all learning is mediated – as we have seen, much is incidental and reflective – but in the context of a formal intervention, media selections will always have to be made. The options have increased over time. All learning was, of course, originally conducted face-to-face, providing an immediacy to the interaction, a rich sensory experience (you see, you hear, you touch, you smell) and, if you’re lucky enough to be one-on-one, the ultimate in personalisation.

Books, when they arrived, provided the counterbalance, by allowing learners more independence and the ability to control the pace. The invention of the telephone provided additional connectivity for learners and tutors working at a distance. Videos, CDs and all their variants added to the diversity of offline media and made high-quality audio and video available to distance learners.

But perhaps the most significant new medium made available by technology is the networked computer, connecting learners to more than two billion other Internet users and countless billions of web pages. ‘E-learning’ is the rather inadequate name we give to the use of computer networks as a channel to facilitate learning. This channel supports a wide range of synchronous and asynchronous media, as shown below:

| Synchronous (real-time) online media | Asynchronous (self-paced) online media |

|

Chat rooms Instant messaging Web conferencing Multi-player virtual worlds |

Web pages Downloadable documents and media files Forums Blogs Wikis Social networks Single-player virtual worlds |

Coming next: A review of top-down and bottom-up formal approaches and conditions for success

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Working with subject experts 2 – building a relationship with your SME

As with any important stakeholder, your first job is to establish a good working relationship with your SME. A good way to start is to read up all you can about the subject in question, particularly any materials already created by the SME. You’re unlikely to remember it all, but at least you will have an overall picture of the subject in question, be aware of some of the terminology, and have an idea of the important issues. Don’t expect the SME to have spent as much time beefing up on their knowledge of learning design, although they will certainly have ideas of their own to bring to the table, however ill-informed.

Right from the start it pays to be absolutely clear what you expect from the SME and what they can expect from you. They are the expert on the subject matter. You are the expert on adult learning. Your job is to construct a solution that will meet a performance need in the organisation. You cannot do this without the benefit of their experience and wisdom. Be 100% clear that your task is not to replicate the SME’s wisdom in every member of your target audience, just to make sure these people can do their jobs. It takes years, if not decades, to build true expertise. You may only have 30 minutes.

Perhaps the biggest barrier to you getting the project ready on schedule is the time it takes to get SME approval of your designs and scripts. This work is almost always underestimated, leading to all sorts of delays and disruptions. It’s best to spell out quite clearly when you will require SME time and for how long. Show the SME a typical design document or script so they know what to expect. Explain that approvals, while perhaps not completely binding, will be regarded as permission to proceed with the next stage of the project. Changes can still be made, but only with a corresponding risk to the schedule and budget.

Don’t bore your SME with learning jargon. They will find this every bit as impenetratable and uninteresting as you (and your target population) may well find their subject expertise. But using plain English isn’t the same as acting dumb. You have a duty as a professional to make clear how it is that adults learn best. Surprisingly, this isn’t common sense. If it was, why are so many learning experiences no more than a knowledge dump. Explain how hard it is to engage the learner, to get them to focus enough on an idea to hold it in long-term memory and then be able to retrieve this learning when it really matters – doing the job. Transmitting information is the easy bit – your job of making it stick is really hard.

Back to: Part 1

Coming in part 3: Asking the right questions

First published in Inside Learning Technologies, November 2011

Social contexts for formal learning

![]()

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth part of chapter 7:

Learning can take place in a variety of social contexts ranging from the self-study through to learning in large groups. These contexts have a major impact on the effectiveness of the intervention and so some care must be taken in choosing the right social context, or combination of contexts, for each intervention.

The learner alone: When the learner works alone they enjoy an obvious increase in flexibility – they can determine when they learn and for how long, the pace of the learning, and the location. We know from surveys that learners value the ability to control the pace of their learning above all other factors. We also know that they value being able to learn in small, digestible chunks.

On the other hand, self-study has its drawbacks. Unless specific deadlines are set, the learner has to make all the running in terms of motivation, a difficult task when you consider that learning is rarely that urgent, and must compete with a myriad of short-term priorities. There’s also the problem of isolation: unless the self-study activity is supported, the learner has no-one with whom they can discuss issues or resolve any misunderstandings. And without a group of peers, learners have no access to alternative perspectives and experiences, and don’t receive the additional motivational boost that comes with peer pressure.

Self-study is being used more and more for formal learning, typically through the medium of interactive online materials. This approach can work well for shorter courses, but has limitations when the learning is more complex and multi-faceted, and when engagement with trainers and peers is critical to the outcome. In these cases self-study may still play a role, but only as an element within a blend.

Learning one-to-one: When used for the right purpose and well executed, one-to-one learning can be more effective than any other approach; that’s because the learner has the undivided attention of a full-time instructor/coach/mentor, who can adapt their responses to the particular needs of the individual learner.

There are limitations to the approach however: the low trainer-to-learner ratio is time-consuming and therefore slow and highly expensive; and there are also obvious limitations on the activities that can be carried out, given the absence of a group of learners.

One-to-one learning is unlikely to be used as the principal approach in a formal learning intervention, although it is widely used in more informal situations such as on-job training and coaching. Its primary use in formal learning is as an ingredient in a blended solution.

Learning in groups: Most of the formal learning that we have encountered has been in groups, typically in a classroom. By learning in groups we experience some powerful advantages: we can share experiences and perspectives, we can engage in discussions, we can work together on practical activities, we can share each other’s successes and disappointments.

Where group events fall down is when they are used as a way to deliver large quantities of information. Unless a group is wholly homogeneous, which is practically an impossibility, some learners will be lagging behind and some will be frustrated at the slow pace; some will be interested in the topic and some not; some will want to ask lots of questions, others will not have the confidence. And when these events are face-to-face, the likelihood is that they will go on for far too long and cause cognitive overload for just about every participant.

Undoubtedly group learning will continue to play a dominant role in formal learning, even if more of this switches to online delivery and an element becomes asynchronous (using tools such as email, blogs and forums).

Each of the three social contexts provides us with considerable scope to employ a wide range of educational and training methods, as shown by the table below:

| The learner alone | Learning one-to-one | Learning in groups |

|

Reading Planning Reflecting Researching Completing questionnaires Completing interactive lessons Problem-solving Viewing recorded video Listening to recorded audio Participating in single-player games and simulations Completing drill and practice exercises Completing assessments Undertaking assignments / projects Visiting other departments / organisations Work experience Using performance support / reference materials |

Receiving instruction Receiving subject-matter support Receiving coaching Receiving mentoring Reviewing progress |

Receiving lectures / presentations Receiving instruction Receiving subject-matter support Engaging in discussions Engaging in group problem-solving activities Engaging in multi-player games and simulations Engaging in role plays and other practical exercises Visiting other departments / organisations Undertaking group assignments / projects Engaging in group progress reviews Networking Collaborating on content development (e.g. with a wiki) |

Interestingly, the methods listed above are practically timeless – the list would have been much the same a hundred years ago, perhaps a thousand. Only a few of the methods are dependent on any technology: reading, obviously, which required the invention of printing; and viewing video and listening to audio would not have been possible until some form of recording mechanism was developed. Although the range of methods doesn’t change much, the choices we make amongst them most certainly do, influenced by advances in educational psychology and neuroscience, political viewpoints, fashions and the changing expectations of next generation learners.

But these choices really do matter. As Sitzmann et al confirmed, ultimately it’s the instructional method, not the delivery medium that makes the difference. When web-based instruction and classroom instruction that have similar methods were compared, there was little or no difference in outcomes. Thomas L. Russell undertook an analysis of more than 350 studies conducted over the past 50 years, each attempting to compare the effectiveness of one learning medium with another. The title of Russell’s book is The No Significant Difference Phenomenon, which says it all.

References

The comparative effectiveness of web-based and classroom instruction: a meta-analysis by T Sitzmann, K Kraiger, D Stewart and R Wisher, published in Personnel Psychology (2006).

The No Significant Difference Phenomenon by Thomas L. Russell, online at http://www.nosignificantdifference.org/

Coming next in chapter 7: Media for formal learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Working with subject experts 1 – why are SMEs such a problem?

The theory is straightforward enough. You’re the content design expert. You want to create some learning content but, in order to do this, you need to clarify the goals for this content and, as a result, what it needs to cover. You seek out someone who’s an expert who can help you with this. You meet with this expert and they provide you with all the information you need and no more. They leave you to work out how – if at all – you use all this. At key stages in the process of design, the expert casts a helpful eye over your work just to make sure you’ve got it all straight. They even throw in ideas for ways you could get some of the information across for you to use if you see fit. You get the content designed and developed on schedule and it learners find it helpful. Both you and the expert are happy to take a share of the credit.

OK, things may not always go so smoothly. Perhaps they never do. But they certainly can if you take the time to establish the right relationship with your subject matter expert (SME) and then make sure you ask the right questions. It would be no exaggeration to suggest that getting this right could make or break your project.

So, why are SMEs such a problem?

The first problem is that there is no such thing as an SME. At least, no-one has that as their job title. Generally speaking, SMEs are co-opted on to your project because they are the ones who know how things are done. They also have a day job and that will undoubtedly be their first priority.

An even greater problem is that SMEs are experts. Sure they are supposed to be, but this provides you with a major obstacle to overcome. In their 2007 book Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath describe the ‘curse of knowledge’, the difficulty that experts have in empathising with novices and with the difficulties that novices face. They find it hard to conceive that people exist with less enthusiasm for their subject than they do, and less appetite to lap up every last morsel of information.

Over time, experts (and this includes you, because just about everybody has become expert at something, even if just playing Angry Birds) build elaborate schema in their brains that connect together the various facts, concepts, rules and principles that underlie their field of interest. They may not be aware of it, but by virtue of millions of synaptic connections, they have a fully functioning, working model to guide them in dealing with all the problems and decisions they have to deal with on a daily basis. They are rarely overloaded by new information. In fact they are always thirsty for more.

Novices, on the other hand, do not have the benefit of all this understanding built up over years of experience. When confronted with a completely new subject, they struggle to relate this to what they already know. They are not sure what’s important, what’s superfluous and what’s plain wrong. They are easily overwhelmed by new information. What they want is the absolutely essential information explained to them as quickly and simply as possible, and then a chance to put this into practice straight away. In this respect, SMEs are not always a lot of help.

Coming in part 2: Building a relationship with your SME

First published in Inside Learning Technologies, November 2011

Strategies for formal learning

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 7:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 7:

Formal learning comes in many shapes and sizes. The effectiveness and efficiency with which a formal learning intervention is delivered depends to a large extent on whether the shape and the size are appropriate for the job.

Clark and Wittrock devised a useful model for analysing training strategies according to the degree of control imposed over the learning process by the trainer and/or the student. At the most trainer-centred end of the spectrum is simple exposition – the trainer tells the learner things, using methods such as lectures or prescribed reading; no interaction is expected or required, except perhaps some Q&A or an assessment.

The second strategy – structured instruction– is still under the trainer’s overall control, but is much more interactive, allowing the trainer to fine-tune the process to the needs of the particular audience. Structured instruction is widely used in training, and includes most classroom sessions and most computer-based self-study materials. Novices will rely on this degree of structure; independent learners can often do without.

A more learner-centred strategy is guided discovery. In this case, learners engage in tasks that have been specially designed to provide them with opportunities to experiment with alternative approaches. Learners improve their skill or understanding by reflecting, with the help of facilitators, coaches or mentors, upon the outcomes of these tasks and, as a result, drawing general conclusions which they can apply to future tasks. Guided discovery allows learners to have a go and learn from their mistakes. This strategy can be deployed in the classroom, in outdoor settings (as with Outward Bound-style courses) or through computer-based case studies, games and simulations.

The final strategy in Clark and Wittrock’s model is exploration. Here each learner determines their own learning process, taking advantage of resources provided by trainers and others, and takes out of this process their own, unique learning. Exploration may seem a relatively informal strategy, but can be integrated into formalised interventions as a component in a blended solution.

A formal learning intervention may rely on just one of these strategies, but increasingly will use a combination. The choice of strategy will depend on the nature of the learning objectives, the prior knowledge and the expectations of the target audience and, to some extent, the preferences and values of the trainer.

References

Psychological Principles of Training by Ruth Clark and Merlin C Wittrock,published in Training and Retraining, Macmillan Reference USA (2001).

Coming next in chapter 7: Social contexts for formal learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating reference information: part 3

![]()

In part 1, we examined how reference information differs from other learning content, the purposes it fulfils and the formats that it can take. In part 2, we explored best practice in terms of the presentation of information. In this third and final part, we look at the various ways you can provide access to your information

Tables of contents

Tables of contents (TOCs) are usually associated with print publications but still have a valid role to play in digital media. Whereas searching can be a rather hit and miss affair, a TOC provides an organised and orderly gateway to a body of information. Every situation is different, but there are some general rules that will help you in preparing a TOC:

- Organise the table in a way that makes sense to your user, not what is easiest for you. Think of all the situations in which a user might come to your information and how they would expect to drill down to find what they want. Should the information be organised in task order, by category, chronologically or alphabetically?

- Keep menus to a reasonable length while keeping the loading of new menu pages to a minimum. This might sound an impossible compromise to make, but there are all sorts of ways of hiding and revealing lower-level menu items using the sorts of tree menus you find in your computers file managers.

- Draw your user’s attention to the most commonly sought after items of information. You could even have a top ten list.

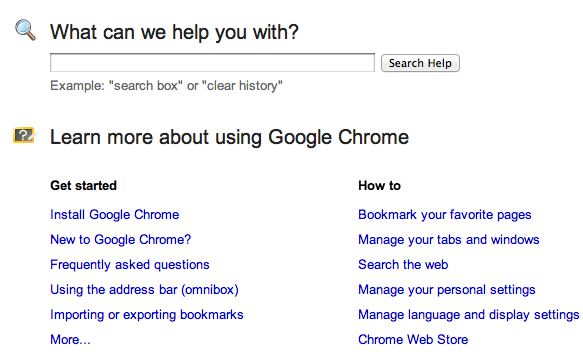

Search

Search used to be considered a rather unfriendly way for users to access information, but search technologies and users skills in searching have come on in leaps and bounds. The advantage from a user’s perspective of using search over a TOC is that it shortcuts all that drilling down through menus. A search facility is now expected and should definitely be provided if at all possible.

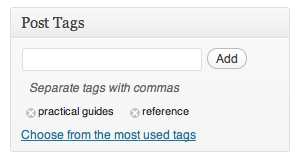

Search can be improved by tagging, the process whereby descriptive labels are applied to content. The process of tagging can be managed on a top-down basis, by content authors, or bottom-up, when users supply their own labels.

Making suggestions

Another way to get users to information that they could find useful is to provide them with intelligent suggestions. An easy and obvious way to do this is to provide ‘Related items’ links at the bottom of each piece of information. You could go a little further by building up a profile of each user and then suggesting links that you know from their past usage history would be relevant to them – something like what Amazon do with their ‘People who bought this title also bought …’ suggestions.

Peer recommendations are always the best, so you may also want to provide a facility to let users recommend items of content to their colleagues, perhaps by emailing them a web address or through some social networking tool.

Unless you have a great deal of programming expertise at your disposal, chances are you’ll be limited in the way you can provide access to information by the tools already available to you. Where you do have choices, use them wisely. Listen to your users and let them tell you what they find useful and what’s just dressing.

This guide is now available as a PDF download

Coming next: Sorry, that’s all our practical guides finished. Unless there’s something we’ve missed … ?

The transfer of learning

![]()

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 7:

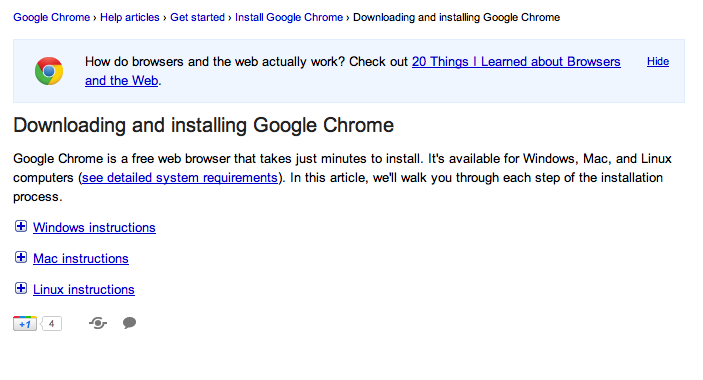

A formal learning intervention is only successful if it results in lasting change in the learner’s behaviour on the job. In their 1992 book Transfer of Training, Mary Broad and John Newstrom estimated that “…merely 10% of the training dollars spent result in actual and lasting behavioural change.”

When assessing what made the biggest impact on transfer of learning, the authors looked at three different parties – the learner’s manager, the trainer/facilitator and the learner themselves – at three stages in the process – before the intervention, during and after. They found that the greatest impact was made by the learner’s manager in setting expectations before the intervention; next most important was the trainer’s role before the intervention in getting to know the needs of the learners they would be training; third most important was the manager’s role after the intervention.

| Before | During | After | |

| Learner’s Manager | 1 | 8 | 3 |

| The trainer/facilitator | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| The learner themselves | 7 | 5 | 6 |

References

Transfer of Training by Mary Broad and John Newstrom, Basic Books, 1992

Coming next in chapter 7: Strategies for formal learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect