![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fifth part of chapter 6:

Bottom-up learning will happen to some extent regardless of the efforts put in by the employer to smooth the process. It’s natural for an employee to take the initiative if they don’t know how to complete a task, because they want to do a good job. It will surely be the exception rather than the rule for someone to simply sit down, fold their arms and wait to be told. However, it’s the role of managers – and the l&d specialists who support them – to do more than just leave things to chance. Bottom-up learning can be positively encouraged, by ensuring employees have the means, the opportunity and the motive to contribute to each other’s learning.

Let’s start with the means and in particular the software tools that can provide the infrastructure to support bottom-up learning:

Blogs provide employees with the ability to reflect on their work experiences and to share those reflections with others who have similar work interests. Where an employee has many peers within the organisation, the blogging software can be made available inside the firewall, which has the added benefit of keeping the content away from the prying eyes of competitors. Where an employee works as a specialist and has few internal peers, they may be encouraged to blog on the World Wide Web where they can benefit from the expertise of similar specialists around the world. Assuming they are not critical of the employer – and you would need a policy to cover this – an external blog may even have a positive PR benefit for the organisation, demonstrating thought leadership in a particular discipline.

Search engines are an essential component in any bottom-up learning infrastructure. We all know the power of Google to help us hunt down information and, for any organisation which has an intranet or a substantial collection of online documents, a similarly powerful search facility behind the firewall is essential.

Yellow pages or their software equivalent, allow employees to seek out experts who may be able to help them solve a current problem. If you don’t have the software to do this in a structured fashion, you can always provide a simple list of who to call for what type of information, on the intranet or in hard copy on a notice board. Once an employee has identified the right expert to contact, they need the right communications medium to put forward their question, whether that’s the telephone, email, instant messaging, web conferencing, SMS messaging or some other format. With this proliferation of communication media, organisations might consider issuing some guidelines to help employees choose the right medium for each particular situation.

Forums (or message boards or bulletin boards, as they are sometimes called) provide a simple way for employees to post questions online, with the hope that somewhere in the community another employee will be able to provide a helpful response. Where forums can let you down is when you are depending on other users to visit the forum site in order to see the latest questions. Some element of ‘push’ is required to alert users to new questions, whether that’s email notifications, RSS feeds or lists of recent postings that appear on the intranet home page.

Wikis provide a way for employees to collaborate in creating content that can be of use to the whole community. Although subject experts and l&d professionals may prime a wiki with content, the ability of all employees to make contributions based on their own particular experiences, makes a wiki much more than a simple reference manual.

Learning management systems (LMSs) can help employees to find e-learning content that is available for open access on an ‘as needs’ basis. It’s important to keep the barriers between the employee and the content to a minimum. Ideally employees should not have to log in separately to the LMS; the available content should be sensibly categorised; the content should be tagged so it can be easily found using the LMS’s own search facilities; the registration/sign-up process should be minimal; and employees should be allowed to rate content, so the most popular and useful content is clearly visible.

Social networking is usually seen as an out-of-work activity, where people use software such as Facebook, MySpace or Bebo to maintain their network of contacts for purely social reasons. However, in just a few years, social networking has grown so quickly, and exerted such a powerful influence on its users that many organisations are now looking for ways to achieve similar benefits inside the firewall. An organisation’s own social network could be used to allow employees to connect with others who have similar needs and interests, to find sources of expertise, to form communities of practice and to keep up-to-date on developments in their particular fields.

Of course, tools are not enough in themselves; employees also need the skills to use them. Although many of the tools listed above are extremely easy to use and many employees will be familiar with their use outside work, there is room here for top-down initiatives to ensure all employees know which tool to use in which circumstance and have the confidence to become active users.

In his ‘How to save the world’ blog, Dave Pollard lists a number of ways in which organisations can achieve quick wins with bottom-up knowledge management initiatives, by skilling up employees to make better use of the tools at their disposal:

“Help people manage the content and organisation of their desktop: Most people are hopeless at personal content management but don’t want to admit it. Provide them with a desktop search tool and show them how to use it effectively.

Help people identify and use the most appropriate communication tool: Give them a one-page cheat sheet on when not to use e-mail and why not, and what to use instead. Create a simple ‘tool-chooser’ or decision tree with links to where they can learn more about each tool available.

Teach people how to do research, not just search: If people are going to do their own research, they need to learn how to do it competently. Most of the people I know can’t.”

Coming next in chapter 6: Then they need the opportunity

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Category: Blog

I'm speaking at DevLearn 11

If you’re looking for somewhere to spend the first week of November, when the cold and dark have set in and yet Christmas is still two months away, then why not head down to the deserts of Nevada, where a whole load of e-learning folk will be gathering to have some fun and learn a few things.

Well I’m going to be at DevLearn 2011, a conference hosted by the eLearning Guild. I’ll be presenting a one-day pre-conference workshop entitled Designing Next-Generation Blended Learning Solutions on Tuesday, Nov. 1. I’m then running a session on The New Learning Architect on Friday, Nov 4.

If you can’t be there, you can always read the books! See The Blended Learning Cookbook and The New Learning Architect.

Training's long tail

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the fourth part of chapter 6:

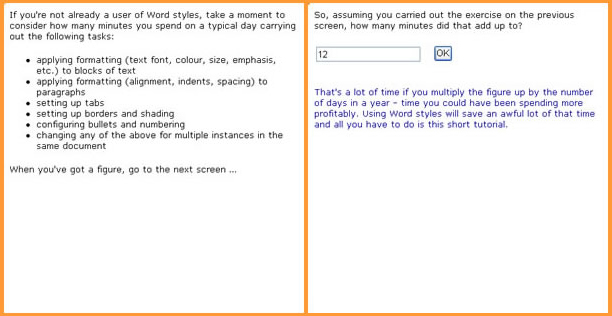

The phrase The Long Tail was first coined by Chris Anderson in 2004 to describe the niche strategy of businesses, such as Amazon.com, which sells a large number of unique items in relatively small quantities. Whereas high-street bookshops are forced, by lack of shelf space, to concentrate on the most popular books, shown in the chart below in blue, retailers selling online can afford to service the minority interests shown below in orange. Interestingly, the volume of the minority titles exceeds that of the most popular, yet before the advent of online retailing, these needs would have been very hard to service.

The concept of The Long Tail fits well with the argument for bottom-up learning. Top-down efforts can only seek to address the most common (or, as we have seen, sometimes the most critical) of needs. It is simply not possible, given available resources, for l&d professionals to design and deliver an appropriate solution to satisfy every learning requirement in their organisations. Instead, when it comes to corporate learning and development, it is bottom-up learning that must address training’s long tail.

In the end it comes down to priorities – putting the effort in where the reward is going to be greatest. At risk of over-simplifying the issues involved, you could argue that the prioritisation process could be extended across all eight cells of our model, with the most generic and critical needs met top-down, through formalised courses. Less common/critical needs would be met by less structured proactive methods; if not, then at the point of need; if not, then through a process of structured reflection. As we extend into The Long Tail, bottom-up approaches come to the fore, starting with formal external programmes and continuing across the four contexts:

Tony Karrer argued that: “To play in The Long Tail, corporate learning functions will need to:

- find approaches that have dramatically lower production costs, near zero;

- look for opportunities to get out of the publisher, distributor role such as becoming an aggregator;

- focus on knowledge worker learning skills;

- help knowledge workers rethink what information they consume, how and why;

- focus on maximising the “return of attention” for knowledge workers rather than common measures today such as cost per learner hour.”

References:

The Long Tail by Chris Anderson, Wired, October 2004.

Corporate Learning Long Tail and Attention Crisis by Tony Karrer, eLearning Technology blog, February 19, 2008.

Coming next in chapter 6: First they need the means

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

How much learning should be bottom-up?

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 6:

It is conceivable that an organisation could manage without any top-down learning interventions at all, relying on employees who were independent learners, good communicators, willing to share their expertise and keen to support each other. More realistically, an organisation will need to make a judgement about how much will be top-down and how much bottom-up, based on a wide range of factors that will differ enormously both between organisations and within them. Here are some guidelines for identifying the situations in which bottom-up learning will be most appropriate:

Where there is constant change and fluidity in tasks and goals: Some organisations are lucky enough to enjoy relatively stable policies, procedures and systems; for many others, particularly those which employ a large number of knowledge workers, the opposite is true – everything seems in a constant state of flux. In this situation, it is almost impossible to create top-down interventions fast enough to satisfy the need; you simply must depend on bottom-up processes to fill the gap.

For knowledge and skills that are used infrequently: If we apply the Pareto principle, then it is realistic to assume that 20% of all the knowledge related to a particular job will be adequate to cover 80% of the tasks. The remaining 80% of knowledge is used only occasionally and can probably therefore be handled using more informal, bottom-up methods, including the use of forums, wikis and similar tools. Some care needs to be taken that, within the less-commonly used knowledge and skills, there are none which are nevertheless critical. A good example would be emergency procedures – these should certainly not be left to chance and should therefore be tackled through a formal, top-down intervention.

When expertise is widely distributed: It is hard to place too much emphasis on bottom-up processes when expertise is centred around a small number of key individuals – these people would be simply overwhelmed by the never-ending requests for help that they would inevitably receive. In these situations, it makes more sense to capture this expertise using more structured, top-down methods. On the other hand, there are many situations in which it is true to say that ‘nobody knows everything and everybody knows something’. Where expertise is widely distributed, bottom-up methods are much more likely to thrive.

Where there are fewer people who need the learning: With scarce resources, l&d departments must focus on those needs which are highly critical or which impact on large numbers of people. There are simply not enough hours in the day to create top-down programmes for every small group that has a shared need. Here again, bottom-up methods fill the gap and ensure that needs don’t go unmet.

Where the employees are more experienced: Experienced employees have the advantage of generalised knowledge about situations and events stored in long-term memory, which make it very much easier for them to absorb new information. Whereas novices benefit from more structured learning experiences, in which they are led step-by-step through new information with the aid of an expert facilitator, more experienced employees can be given much more latitude to help themselves.

Coming next in chapter 6: Training’s long tail

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

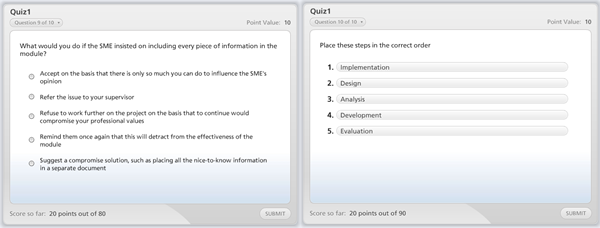

A practical guide to creating quizzes: part 2

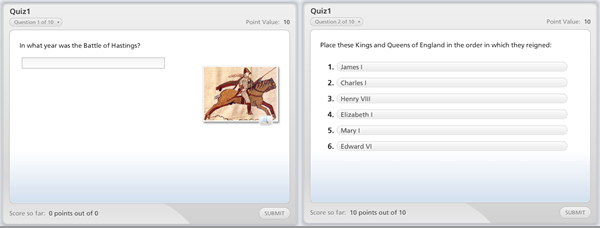

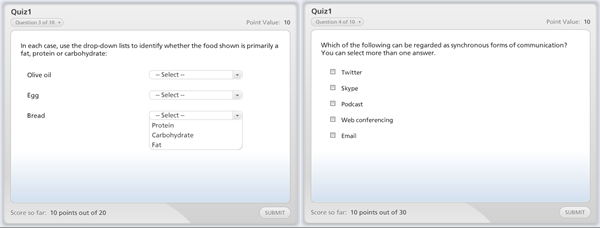

![]() In part 1, we looked at the characteristics of online quizzes and explored how they could be used to assist or assess learning. In this instalment, we look at the various question formats and the types of learning for which they are suited.

In part 1, we looked at the characteristics of online quizzes and explored how they could be used to assist or assess learning. In this instalment, we look at the various question formats and the types of learning for which they are suited.

Factual knowledge

In an adult learning context, factual information is usually supplemental to the core learning objective and more often than not just for general interest. However, some facts really do need to be known by heart: When was … ? What is … ? Who is … ?

If it is essential that the learner can recall the information without prompting, then you have little choice than to ask a question that requires them to type the answer in. If it is only necessary that they are able to recognise the right answer, then various forms of multiple choice will do.

Conceptual knowledge

Concepts provide a common language for understanding a subject. Generally the aim is for the user to be able to identify the class or category to which given objects belong, whether these are tangible (like types of computer) or abstract (like schools of thought). The most common way of checking this knowledge is to provide the learner with examples and ask them to place these in the correct categories, as in the examples below:

Process knowledge

A process explains how something works as a chain of cause and effect relationships. To check understanding of a process, you can ask questions about causes or about effects, as shown below:

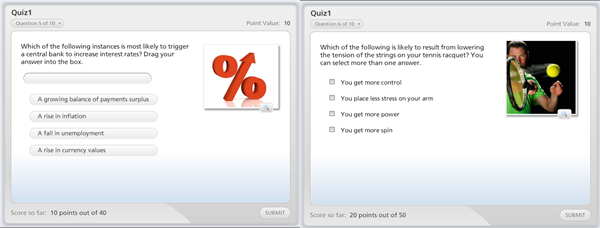

Spatial knowledge

In this instance our aim is for the learner to be able to identify the locations of parts of an object, device, physical space or system. The easiest way to check this knowledge is with a question that has the learner click on a given part as shown below:

Procedural knowledge

Procedural knowledge is tougher because in many cases what you really want to test is whether the learner can actually carry out the procedure rather than just answer questions about it. However procedural knowledge is a first step and you can use a variety of questions to check learning:

These examples were created in Articulate QuizMaker, although many quiz tools could do a similar job. In the next instalment we look at the principles underlying the writing of quiz questions.

Why bottom-up learning is needed

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the second part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the second part of chapter 6:

Imagine a scenario in which no bottom-up learning took place, in which all learning was regulated and controlled by management, and in which the l&d department invariably took the lead. Here’s what might happen:

- The l&d department knows exactly what knowledge and skills are required for each job position and are kept completely up-to-date about any changes to jobs and requirements.

- Regular performance appraisals and other forms of assessment mean that line management are fully aware of any knowledge and skill gaps, and keep the l&d department fully informed about these.

- The l&d department is resourced to provide solutions to meet all known knowledge and skills gaps, using carefully-planned, top-down interventions.

- Employees do not need to worry about the knowledge and skills they need to meet current or future requirements because their employer is in complete command of the situation.

Sounds like it’s all under control. On the other hand, this might also be the outcome:

- The information held by the l&d department regarding jobs and skills is too out-of-date to be of any use.

- The l&d department does not have the resources to respond to anything except the most generic of needs.

- When important changes are made to systems, processes and policies, the l&d department takes too long to develop top-down interventions to support the changes.

- Knowledge requirements change so quickly that it is impossible for training programmes and job aids to be kept up-to-date.

- There is such a diversity of jobs in the organisation that there is insufficient critical mass to justify the design and delivery of any formal interventions.

- Expensive top-down interventions are delivered when employees are perfectly capable of meeting any needs for themselves informally.

While top-down learning is needed to control risk, bottom-up learning is needed to provide responsiveness. Few organisations have the luxury of being in complete control of all aspects of the training cycle – even if it was possible to attain this position, it would probably not be cost-effective. Bottom-up learning fills the gaps by providing a response to urgent situations and by meeting the needs of minorities. It’s quick, it’s flexible, it’s empowering. That’s why bottom-up learning plays a valuable role in any learning and development strategy.

Coming next in chapter 6: How much learning should be bottom-up?

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

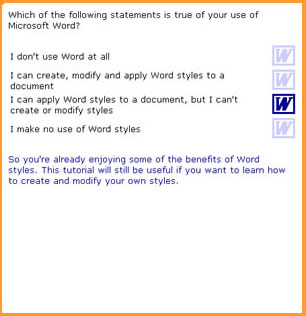

A practical guide to creating quizzes: part 1

![]() We all know what a quiz is. It’s a test of knowledge, typically accomplished by asking a series of questions.

We all know what a quiz is. It’s a test of knowledge, typically accomplished by asking a series of questions.

Quizzes are popular in the digital environment, not least because computers find it so easy to deliver the questions and score the answers. In fact, if you were in your first week of a programming course, you’d probably have a go at putting together a multiple choice quiz. Quizzes are an entertaining diversion, particularly when delivered within the context of a game, with rules, levels, competition and prizes, but they can also play a useful role within a learning solution. A function that is often abused, perhaps, but the potential is there.

Media elements

Although many quizzes are primarily textual, the possibility is there to use every media element. Images can provide the basis for questions that test for recognition of people, objects or places or to locate elements within interfaces and other spaces. Video can be used to portray situations that test the learner’s ability to make critical judgements. Audio can be employed to check for recognition of voices or pieces of music. A variety of media can also be used to introduce questions and provide feedback.

Interactive capability

Quizzes are essentially interactive. They serve their function in testing knowledge only by eliciting responses from learners. Just about any input device imaginable can be used as the basis for that interaction – key presses, mouse clicks, touches, the lot.

Applications

The most common application for a quiz is as a test of mastery. This is fine in principle as long as it really is possible for the knowledge and skills in question to be assessed by the sort of questions that a computer can deliver. To state the obvious, you might be able to check that a pilot understands the principles of aerodynamics using a quiz, but you can’t check they can fly the plane. Some caution also needs to be taken in terms of when a quiz is delivered. If the quiz comes right after the delivery of content (and the learner knows it’s coming), it is all too easy for the learner to hold on to enough of the information to get them through the quiz, but then forget it all the day after. We can probably all remember how possible it was to cram in information before an exam, only to see that evaporate almost as soon as we committed it to paper. A much more valid test of knowledge comes weeks, months or years after original exposure to the information.

Although their potential is rarely exploited to the full, quizzes can actually play a useful role at just about every stage in the learning process:

- As a way, right up front, for the learner to find out how much they already know and how much they need to know. This sort of diagnostic pre-test not only demonstrates the need for learning, it helps to direct the learner to content that is likely to be most useful.

- As a vehicle for delivering the learning content itself. One way to create an engaging lesson is to use a series of quiz questions to challenge and then build on the learner’s prior knowledge. Every question alerts the learner to a gap to fill and all you have to do is oblige.

- As a means for repetitive drill and practice. Unlike teachers, computers never get bored asking questions and they don’t lose their patience when the learner takes a little longer than expected to get the point. In the classroom, most knowledge is under-rehearsed and most skills under-practised. Quizzes represent a good way to remedy that.

So how do I get started?

There is no shortage of tools for creating quizzes. Most cover the usual range of questions types – multi-choice, multi-answer, free text response, sequencing, matching, selecting hotspots and all sorts of variations. All e-learning authoring tools come with a quiz making capability, plus there are specialist stand-alone tools, including ones that you can use for high-stakes assessments or for quiz games.

In practice, it’s likely that tools will be the least of your problems. Writing the questions is a much more challenging task, and that’s where we’ll be directing our attention next.

Coming in part 2: using the correct question for the job

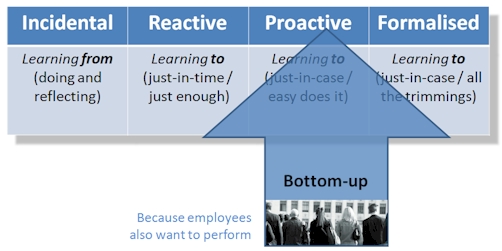

The scope of bottom-up learning

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 6:

Bottom-up learning occurs because employees want to be able to perform effectively in their jobs. The exact motivation may vary, from achieving job security to earning more money, gaining recognition or obtaining personal fulfilment, but the route to all these is performing well on the job, and employees know as well as their employers that this depends – to some extent at least – on their acquiring the appropriate knowledge and skills.

Bottom-up learning occurs in each of the four contexts that we have described previously:

Experiential: Experiential learning is essentially reflective – ‘learning from’ rather than ‘learning to’. This process can be initiated by the individual without any deliberate action on the behalf of the employer. At its simplest, this might mean no more than sitting back and thinking over events that have occurred, whether these events directly involved the individual or whether they were merely observed. If an event had a negative outcome, the question needs to be asked ‘why did this happen?’ Could the outcome be avoided in future or mitigated in some way. If the outcome was positive, it is just as important to know why. Why can be done to replicate this successful outcome, or to exploit it if it occurs again? The process of reflection becomes interactive when it takes the form of a discussion – talking things over. And it becomes more disciplined when it is made explicit through blogging. Employees can also choose to expand the opportunities they have for learning experiences by ensuring they maintain a healthy work-life balance. Out-of-work activities such as hobbies, travel and voluntary work will often have parallels at work. By maximising the scope for new sensory input, individuals increase the chance that they’ll build valuable skills and insights that they can apply in their jobs.

On-demand: When it comes to just-in-time learning, employees have always needed to rely to some extent on their own endeavours. It is highly unlikely that any employer will be able to predict every item of information that every employee is going to need in every situation, and make that available in the form of some sort of job aid or resource. At simplest, when they’re stuck, employees simply consult an expert, typically the person sitting next to them. Ideally this process will be formalised through some kind of online ‘find an expert’ solution, a sort of corporate Yellow Pages. Increasingly online tools are being made available to support and encourage bottom-up learning at the point of need, notably forums to which questions can be posted, and wikis which can be used to collect together useful reference information.

Non-formal: There’s a number of ways in which employees can set about equipping themselves with the knowledge and skills they need to develop in their roles, without enrolling on formal courses. While each of these methods relies on the employee to initiate the activity, they all tend to require some help from the employer, whether that’s by establishing the appropriate infrastructure or by committing to policies which make opportunities accessible. Some examples include open learning, where the employee takes advantage of learning resources, such as short self-study courses, which the employer makes available for access on demand; social networking software, which allows the learner to establish contacts with others within the organisation who have similar needs; attending external conferences; and enjoying the services provided by professional associations and other external membership bodies.

Formal: You would think that formal courses were an exclusively top-down initiative, but there are plenty of ways in which employees can take the initiative themselves. Perhaps the most obvious examples are postgraduate courses, such as Masters Degrees, and qualifications offered by professional bodies. There are, of course, other less formidable options, such as adult education courses offered by local colleges.

People have many and wide-ranging needs, whether that’s at the level of survival (security, shelter, food, reproduction, etc.), needs of a more social nature (belonging, friendship, recognition) or of a higher order (stimulation, advancement, personal fulfilment, etc.). Directly or indirectly, learning can help an individual to meet many of these needs. To the extent that this learning is reflected in better performance at work, then the organisation has as much to gain as the individual.

While the l&d professional may not determine the ‘content’ of the learning that takes place on a bottom-up basis, they certainly have a role to play in determining the ‘process’. Because it is impractical to meet all learning requirements top-down, it is in the interests of the organisation to encourage relevant, work-related, bottom-up learning. Some of this will happen anyway, regardless of what the l&d department puts in place, but much depends on the right policies and infrastructure being put in place.

Where l&d professionals must be careful, is not being over-prescriptive about the ways in which bottom-up learning occurs. As John Seely Brown and Paul Duquid point out : “The solution to unpredictable demand is systems that are geared to respond to pull from the market and from audiences; built on loosely-coupled modules rather than tightly integrated programmes; people-centric rather than resource or information-centric. There needs to be a willingness to let solutions emerge organically rather than trying to engineer them in advance.”

Reference:

The Social Life of Information by John Seely Brown and Paul Duquid, Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

Coming next in chapter 6: Why bottom-up learning is needed

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Conditions for success

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth and final part of chapter 5:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth and final part of chapter 5:

To summarise, these are the conditions for success with top-down learning:

- Top-down learning interventions are aligned with the business goals of the organisation and measured in terms of the contribution they make to these goals.

- These interventions are designed to meet genuine learning and development needs.

- These interventions are focused on critical and widely used knowledge and skills, and on the needs of novices and those with low metacognitive skills.

- The most resources are allocated to the interventions that deliver the most value to the organisation.

- Senior management is actively involved in determining needs and genuinely committed to helping make learning interventions a success.

- All key stakeholders, including potential learners, are involved in the process of designing and developing the interventions.

- All four contexts (experiential, on-demand, non-formal, formal) are considered in designing the most appropriate form for the interventions.

Coming next, chapter 6: Bottom-up learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning tutorials: part 3

![]() In part 1 of this Practical Guide, we examined the history, characteristics and benefits of the digital learning tutorial. In the second part, we explored some strategies you can use to design tutorials that impart important knowledge. In this third and final part, we look at how tutorials can be used to teach procedures.

In part 1 of this Practical Guide, we examined the history, characteristics and benefits of the digital learning tutorial. In the second part, we explored some strategies you can use to design tutorials that impart important knowledge. In this third and final part, we look at how tutorials can be used to teach procedures.

Engage the learner

As we discussed in the previous part of this guide, you cannot simply assume that the learner will come to your tutorial full of enthusiasm for the topic. Your task is to convey the importance of the topic and its relevance to the learner’s job. The simplest way to do this is just to explain, but you can achieve a more powerful effect through some form of introductory activity.

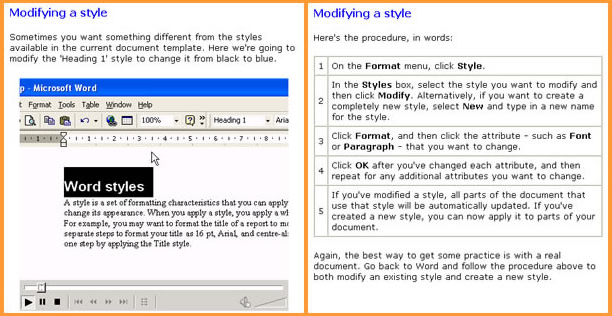

Explain and demonstrate

Your next step is to provide a quick overview of the steps in the procedure. It will help the learner if you present the big picture before going into detail.

Then explain or demonstrate the procedure step-by-step, explaining any special rules that need to be followed at each step.

Provide an opportunity for safe practice

It’s one thing to understand a procedure. It’s quite another to be able to put it into practice. It takes time to turn knowledge into skill and it’s unlikely that your tutorial will do much more than kick-start this process. It’s your job to provide the learner with the opportunity to take their first step, with a simple yet challenging activity which mirrors the real world as closely as possible.

With a complex procedure, you may want to provide a practice activity at each step. In this case, it’s likely that you’ll cover each step in a separate tutorial. Don’t forget to bring the whole procedure together at the end, as in real life steps are not carried out in isolation.

One of the ways that you can provide practice opportunities is using learning scenarios. For more information, see Onlignment’s Practical guide to creating learning scenarios.

Point to the next step

A how-to tutorial is the first step in learning a new skill. In many cases the learner will be able to take things on from there on their own, but where the skills require a great deal more safe practice before they are applied on-the-job, you may find you have to organise further practice opportunities using simulations, role plays and workshop activities.

That concludes this Practical Guide. It is now also available as a PDF download.

Next up: A practical guide to creating quizzes.