![]()

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth part of chapter 7:

Learning can take place in a variety of social contexts ranging from the self-study through to learning in large groups. These contexts have a major impact on the effectiveness of the intervention and so some care must be taken in choosing the right social context, or combination of contexts, for each intervention.

The learner alone: When the learner works alone they enjoy an obvious increase in flexibility – they can determine when they learn and for how long, the pace of the learning, and the location. We know from surveys that learners value the ability to control the pace of their learning above all other factors. We also know that they value being able to learn in small, digestible chunks.

On the other hand, self-study has its drawbacks. Unless specific deadlines are set, the learner has to make all the running in terms of motivation, a difficult task when you consider that learning is rarely that urgent, and must compete with a myriad of short-term priorities. There’s also the problem of isolation: unless the self-study activity is supported, the learner has no-one with whom they can discuss issues or resolve any misunderstandings. And without a group of peers, learners have no access to alternative perspectives and experiences, and don’t receive the additional motivational boost that comes with peer pressure.

Self-study is being used more and more for formal learning, typically through the medium of interactive online materials. This approach can work well for shorter courses, but has limitations when the learning is more complex and multi-faceted, and when engagement with trainers and peers is critical to the outcome. In these cases self-study may still play a role, but only as an element within a blend.

Learning one-to-one: When used for the right purpose and well executed, one-to-one learning can be more effective than any other approach; that’s because the learner has the undivided attention of a full-time instructor/coach/mentor, who can adapt their responses to the particular needs of the individual learner.

There are limitations to the approach however: the low trainer-to-learner ratio is time-consuming and therefore slow and highly expensive; and there are also obvious limitations on the activities that can be carried out, given the absence of a group of learners.

One-to-one learning is unlikely to be used as the principal approach in a formal learning intervention, although it is widely used in more informal situations such as on-job training and coaching. Its primary use in formal learning is as an ingredient in a blended solution.

Learning in groups: Most of the formal learning that we have encountered has been in groups, typically in a classroom. By learning in groups we experience some powerful advantages: we can share experiences and perspectives, we can engage in discussions, we can work together on practical activities, we can share each other’s successes and disappointments.

Where group events fall down is when they are used as a way to deliver large quantities of information. Unless a group is wholly homogeneous, which is practically an impossibility, some learners will be lagging behind and some will be frustrated at the slow pace; some will be interested in the topic and some not; some will want to ask lots of questions, others will not have the confidence. And when these events are face-to-face, the likelihood is that they will go on for far too long and cause cognitive overload for just about every participant.

Undoubtedly group learning will continue to play a dominant role in formal learning, even if more of this switches to online delivery and an element becomes asynchronous (using tools such as email, blogs and forums).

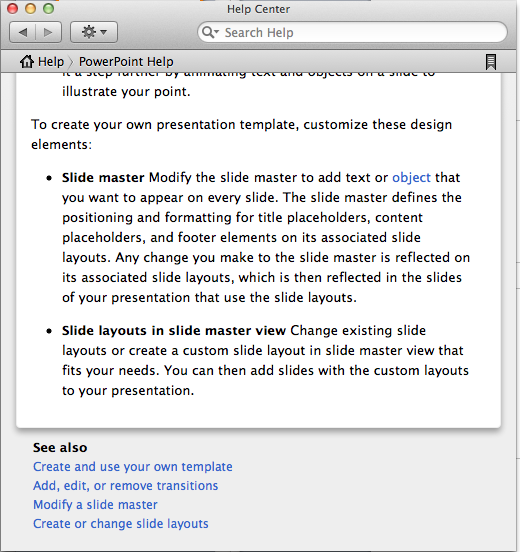

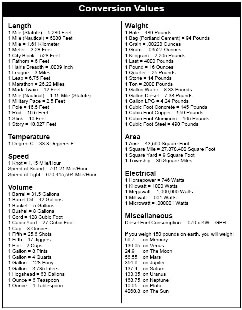

Each of the three social contexts provides us with considerable scope to employ a wide range of educational and training methods, as shown by the table below:

| The learner alone | Learning one-to-one | Learning in groups |

|

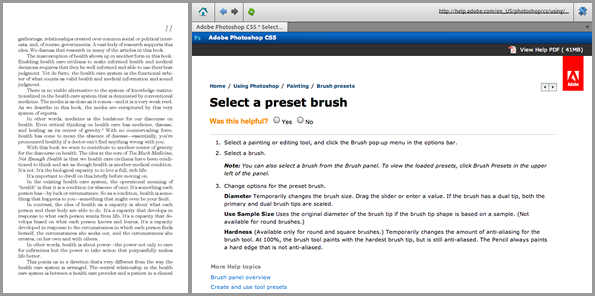

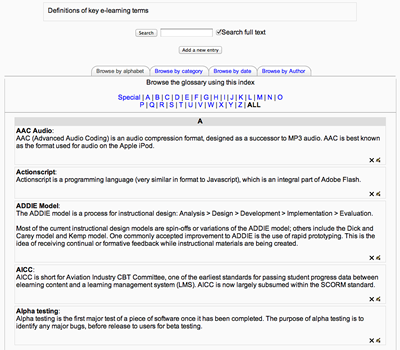

Reading Planning Reflecting Researching Completing questionnaires Completing interactive lessons Problem-solving Viewing recorded video Listening to recorded audio Participating in single-player games and simulations Completing drill and practice exercises Completing assessments Undertaking assignments / projects Visiting other departments / organisations Work experience Using performance support / reference materials |

Receiving instruction Receiving subject-matter support Receiving coaching Receiving mentoring Reviewing progress |

Receiving lectures / presentations Receiving instruction Receiving subject-matter support Engaging in discussions Engaging in group problem-solving activities Engaging in multi-player games and simulations Engaging in role plays and other practical exercises Visiting other departments / organisations Undertaking group assignments / projects Engaging in group progress reviews Networking Collaborating on content development (e.g. with a wiki) |

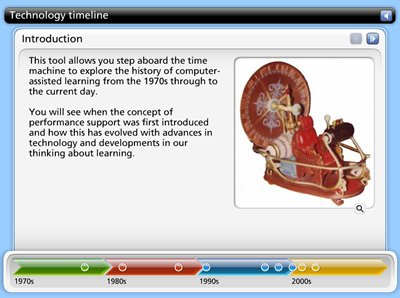

Interestingly, the methods listed above are practically timeless – the list would have been much the same a hundred years ago, perhaps a thousand. Only a few of the methods are dependent on any technology: reading, obviously, which required the invention of printing; and viewing video and listening to audio would not have been possible until some form of recording mechanism was developed. Although the range of methods doesn’t change much, the choices we make amongst them most certainly do, influenced by advances in educational psychology and neuroscience, political viewpoints, fashions and the changing expectations of next generation learners.

But these choices really do matter. As Sitzmann et al confirmed, ultimately it’s the instructional method, not the delivery medium that makes the difference. When web-based instruction and classroom instruction that have similar methods were compared, there was little or no difference in outcomes. Thomas L. Russell undertook an analysis of more than 350 studies conducted over the past 50 years, each attempting to compare the effectiveness of one learning medium with another. The title of Russell’s book is The No Significant Difference Phenomenon, which says it all.

References

The comparative effectiveness of web-based and classroom instruction: a meta-analysis by T Sitzmann, K Kraiger, D Stewart and R Wisher, published in Personnel Psychology (2006).

The No Significant Difference Phenomenon by Thomas L. Russell, online at http://www.nosignificantdifference.org/

Coming next in chapter 7: Media for formal learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect