Before Sir Tim Berners-Lee did us all a big favour some twenty years ago by inventing the World Wide Web, the distribution of content was a very physical process. Regardless of the format – book, CD, DVD or whatever – some form of ‘master’ would be produced and this would be used as a basis for the manufacture of the finished goods. These would then be boxed up and physically distributed to wholesalers, retailers and eventually end customers. The books and CDs would end their journey neatly lined up on shelves or in racks, ready for consumption. How quaint this process is beginning to look come 2012.

While there is still a market for ‘offline media’ (the sort you can use without an internet connection), it is fast dwindling. Sales of printed media, CDs and DVDs are dropping rapidly as the price of computer memory drops and bandwidth increases. Why would anyone clutter up their valuable living space with piles of dusty books and CDs when they can store as many as they could possibly consume in a lifetime on a Kindle, on an iPod or somewhere in the cloud? Why indeed? No-one under thirty would even consider it.

Learning content obeys the same rules. Why burden employees with huge ring binders full of hand-outs and reference manuals to sit unopened on their shelves when the same information can be made available online at the click of a mouse? Information that can be easily maintained, indexed, searched and cross-referenced; and which costs nothing to replicate or distribute.

In the old world, learning content was a bit of an after-thought. The course stood central to all learning activity. Your course manual was not much more than a trophy; something to display in your office to show everyone how much you had supposedly learned.

With the shift from ‘courses’ to ‘resources,’ content becomes critical. No-one expects anymore to have to struggle to absorb large volumes of information during a course. Yes, they want insights into important new concepts and principles. But the rest they want to be able to access quickly and easily if and when they need it. How you distribute learning content is now central to the potential success of any intervention.

Coming in part 2: Choosing a format for your content

First published in Inside Learning Technologies, December 2011

Author: Clive Shepherd

The arguments for being proactive about learning

![]()

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. Here we make a start with chapter 8, which focuses on non-formal learning:

What do we mean by non-formal learning?

We continue our tour of the contextual model with a look at non-formal learning. In a way we’ve already started, because both formal learning, which we reviewed in the last chapter, and non-formal learning are proactive approaches. Formal learning stands apart because it packages up the learning intervention in the guise of a ‘course’, with clearly established objectives, curriculum and assessment. In this chapter we look at the myriad of interventions which are much less formal, but still make a major contribution to learning and development in the workplace.

To refresh your memory, non-formal learning as we define it here is ‘learning to’ with a future perspective. It is not concerned with ‘learning from’ what we have done in the past, nor ‘learning to’ do something right now to address an immediate need. It occurs whenever we take deliberate steps to prepare ourselves for the tasks that we will be carrying out in the future or when others do this on our behalf. Some cynics label it ‘just-in-case’ learning, in contrast to learning that takes place ‘just-in-time’. Non-formal learning takes many shapes, but stops short of those interventions packaged up as formal courses.

The arguments for being proactive

Proactive approaches, formal or non-formal, are important because there are certain fundamental things we need to know and skills we need to have before we can make any serious attempt to function in our present jobs, or take on new responsibilities:

Induction and basic training: We are recruited as much as anything for the skills and knowledge we already possess, for our years of experience with other employers and for our qualifications. But every employer is different in terms of their culture, their particular policies and procedures, and the people that they employ. Even the most qualified new recruit requires some induction whereas, at the other end of the scale, many starters require weeks, months or even years of basic training.

Business change: Only rarely do jobs remain static – responsibilities change along with new strategies, processes and systems, creating new requirements for knowledge and skill.

Development: Looking ahead, organisations and employees themselves have an obvious interest in making preparations for employees to take on greater responsibilities.

Coming next: So why non-formal as opposed to on-demand learning?

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Working with subject experts 4 – what when you are the SME?

It is not that unusual for the content designer also to be the subject expert. After all, many teachers and trainers started their careers by practising what they now preach. If not, then they certainly will have picked up a lot of expert knowledge over years of teaching. Being your own SME has one major benefit and one big drawback.

The benefit is that you have no-one to create a relationship with (assuming you’re feeling OK about yourself) and no-one to question. You can get straight on with the job of design.

The problem is that even teachers (some might say especially) suffer from the curse of knowledge. This means you have to display more than a little self-awareness and exercise a great deal of self-control.

A few years back, an informal community of instructional designers set about developing a guide for those people who were asked to get involved in design but for whom design was certainly not their principle activity (SMEs for example). The project was called The 30-minute masters, on the basis that 30 minutes was all the time a non-specialist would want to spend learning about design. By the time all the ideas were gathered and the curriculum finalised the project had to be renamed The 60-minute masters. So, even design experts find it hard knowing when to stop.

Perhaps it would be better if we left subject experts out of the equation altogether. As Jane Bozarth commented in her post Nuts and Bolts: Working With Subject Matter Experts: “The better choice isn’t always the most experienced worker, but the most recently competent one: that newer person who remembers what it was like not to know how to do a task, who remembers having to learn and what that entailed.”

There’s a thought.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

First published in Inside Learning Technologies, November 2011

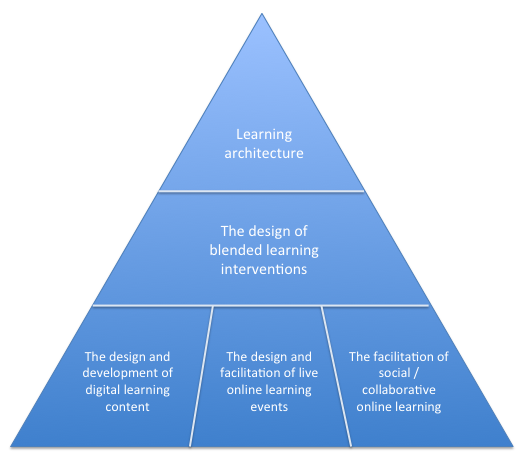

Onlignment's learning pyramid

I’m sometimes asked to explain the difference between the role of the learning architect and the blended learning designer. I see it like this:

The learning architect is responsible for creating an environment that maximises the potential for learning. They carry out this work with a specific population in mind, however large or small. The work that the learning architect does is strategic and does not usually relate to a specific project or intervention.

The blended learning designer, on the other hand, is focused on a specific intervention. Normally this will be formal in nature, in that it represents some form of course, but the blended learning designer will often draw upon methodologies that are non-formal, just-in-time or experiential.

Here at Onlignment we are aiming to put resources and programmes in place that support learning architects and blended learning designers (who could, of course, be the same person), as well as those practitioners who put in place the online elements of the architecture and the specific interventions. At this point we have the following:

For learning architects: paperback and e-book versions of The New Learning Architect, as well as our strategic consultancy services.

For blended learning designers: paperback and e-book versions of The Blended Learning Cookbook (expect edition 3 in 2012), as well workshops on blended learning.

For designers of digital learning content: our new book, Digital Learning Content: A Designer’s Guide will be available in paperback and e-book versions in January 2012; see also our practical guides and workshop.

For facilitators of live online learning: see our free e-book Live Online Online: A facilitator’s Guide, which is also available as a paperback and for Kindle; see also our workshop on this subject.

For facilitators of social and collaborative learning: See our three-part series Getting Started With Social Media as well as our consultancy services.

The formal learning toolkit

![]()

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. Here we bring chapter 7 to a conclusion:

Top-down approaches

Formal learning is most commonly organised on a top-down basis by employers for their employees. They have a wide range of options at their disposal:

Classroom courses

Outdoor learning

Self-study e-learning

Collaborative distance learning

Electronic games and simulations

Blended solutions

Bottom-up approaches

It might seem odd to conceive of formal learning interventions as being anything other than top-down, but there are frequent occasions when the initiative to undertake a course comes from the employee and not the employer. Principally this will occur when the employee wishes to obtain some form of technical or professional accreditation that will enhance their career prospects. Most employers operate some form of scheme to at least part fund these courses, sometimes with provisions for return of this subsidy if the employee subsequently leaves their job before a certain date.

Otherwise, formal learning that is initiated from a bottom-up perspective can take any of the forms described above under top-down.

Conditions for success

To enjoy success with formal learning it is necessary for the l&d professional to recognise the following:

- that not all learning needs to be packaged up as a course – more informal approaches are often perfectly adequate;

- that there are many approaches available for the delivery of courses, not just classroom delivery;

- that sometimes no single approach will do the job and that a blended solution will be necessary;

- that learning must be a process embedded in workplace performance, not an event;

- that trainers are more likely to be effective as ‘guides on the side’ than as ‘sages on the stage’.

Coming next: We move on to focus on non-formal learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Lifesavers for those facing death by PowerPoint

I’ve been experimenting with a fun library of PowerPoint artwork and templates called Doodleslide. It comes in the form of a plug-in for PowerPoint or Word on Office 2003-2010 (PC only, not Mac). If you use Doodleslide artwork throughout a presentation, it will certainly break the mould. It could work just as well for PowerPoint-based e-learning if that’s what you do.

I know it won’t work for every situation, but it will for some, and that’s worth the $49.95. You’d have to be careful mixing it with other styles of artwork, of course, to avoid producing something completely mad, but I’m sure it’s possible. Worth a look.

Working with subject experts 3 – asking the right questions

There are plenty of ways of getting the information you need. The worst way is to get the SME to produce a PowerPoint deck. What you will get is far too much information, expressed almost entirely in bullet points. The SME will be aware that this isn’t the finished article, but expects that somehow you will weave your magic by adding a load of pictures and other decorations, and sticking a quiz on the end. But you’re not going to do that, are you?

Every slide, no every bullet, that you remove from the SME’s slide deck will involve intense negotiations. The SME will be in mourning for ages afterwards, if indeed they ever recover. Better to avoid this process altogether.

One way to research the topic is to sit in on an existing class, perhaps one for which the SME is the instructor. Talk to participants to see what they found useful and what they found confusing. Extract the important learning points, but even more importantly, note down all the instructor’s war stories, examples, anecdotes and jokes. All too often, the reason why learning content is so dull is because it is so matter of fact – it has no personality. The stories are a lot more than entertainment. They provide context and relevance. They allow learners to see patterns and make connections, which is what learning is really all about.

Chances are you’ll also need to interview the SME. Documents and slide decks are OK up to a point but they are a long way from where you want to be. Your focus is on the performance. What do you want the learner to be able to do? What activities can you devise that will allow them to practise doing this? What knowledge does the learner need in order to engage in this activity? Credit is due here to Cathy Moore who spells out the questions to ask as part of the process she calls Action Mapping.

If your SME has only ever experienced knowledge dumps then you may have difficulty communicating what it is that you are aiming to achieve. The best way to overcome this barrier is to show the SME the best example you can find of performance-focused learning content. If you can’t find anything, perhaps you need to create some demo material yourself.

Unless you are really lucky (or skilful), the SME will still want to include more material than you believe is really appropriate. This is the point to make the distinction between courses and resources. The aim of the course is to engage the learner’s interest in the topic and help them to develop sufficient confidence to move forward independently. That is not the end of the story. Learning will continue back on the job and learners will inevitably have many questions of detail, which is where the resources come in, available online, on-demand. Resources are not an optional extra; they are step 2 in the plan. All the information that the SME recommends will be included; it’s just that most of it will be at step 2.

Finally, don’t forget to thank the SME for all their hard work. Even better, credit them on the materials. They will appreciate it.

Part 1 Part 2

Coming in part 4: What when you are the SME?

First published in Inside Learning Technologies, November 2011

Live online learning doesn't have to mean wearing headphones

I know some people spend half their lives with headphones on, but I find even my cushioned, noise-cancelling kit from Bose gets tiring after a while. For Skype and web conferencing I’d love to free myself from using a headset if I could, without losing audio quality or suffering from echoes.

So I was keen to have a play with this equipment from Phoenix Audio Technologies, designed to allow one or more participants to communicate clearly online without having to be up-close to a microphone. It does some whizzy echo cancellation and noise reduction, so even in a busy environment you should be able to come over clearly.

So what applications do these devices have for online learning and communications?

- Use the Duet instead of a headset when you’re on Skype or web conferencing.

- Use the Quattro when you want to include a whole room full of people in a web conferencing session.

- Use the Duet or Quattro as a way to record interviews and discussions for podcasts and videos. Although the Quattro has four microphones, it only provides a mono signal, but that may not matter to you. The sampling rate is a maximum of 16 KHz, which is not brilliant, but this is likely to be fine for everyday online playback. For recording an individual voice, perhaps to narrate a slide show or screencast, you will definitely get better results from a specialist USB condenser microphone such as the Yeti.

Media for formal learning

![]()

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the seventh part of chapter 7:

In contrast to educational and training methods, the options in terms of learning media are growing exponentially. If methods have the main impact on the effectiveness of a learning intervention, then media have the main influence on efficiency – the way in which resources are used to deliver the learning outcomes. The possibilities for efficiencies have grown enormously with advances in technology.

Not all learning is mediated – as we have seen, much is incidental and reflective – but in the context of a formal intervention, media selections will always have to be made. The options have increased over time. All learning was, of course, originally conducted face-to-face, providing an immediacy to the interaction, a rich sensory experience (you see, you hear, you touch, you smell) and, if you’re lucky enough to be one-on-one, the ultimate in personalisation.

Books, when they arrived, provided the counterbalance, by allowing learners more independence and the ability to control the pace. The invention of the telephone provided additional connectivity for learners and tutors working at a distance. Videos, CDs and all their variants added to the diversity of offline media and made high-quality audio and video available to distance learners.

But perhaps the most significant new medium made available by technology is the networked computer, connecting learners to more than two billion other Internet users and countless billions of web pages. ‘E-learning’ is the rather inadequate name we give to the use of computer networks as a channel to facilitate learning. This channel supports a wide range of synchronous and asynchronous media, as shown below:

| Synchronous (real-time) online media | Asynchronous (self-paced) online media |

|

Chat rooms Instant messaging Web conferencing Multi-player virtual worlds |

Web pages Downloadable documents and media files Forums Blogs Wikis Social networks Single-player virtual worlds |

Coming next: A review of top-down and bottom-up formal approaches and conditions for success

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Working with subject experts 2 – building a relationship with your SME

As with any important stakeholder, your first job is to establish a good working relationship with your SME. A good way to start is to read up all you can about the subject in question, particularly any materials already created by the SME. You’re unlikely to remember it all, but at least you will have an overall picture of the subject in question, be aware of some of the terminology, and have an idea of the important issues. Don’t expect the SME to have spent as much time beefing up on their knowledge of learning design, although they will certainly have ideas of their own to bring to the table, however ill-informed.

Right from the start it pays to be absolutely clear what you expect from the SME and what they can expect from you. They are the expert on the subject matter. You are the expert on adult learning. Your job is to construct a solution that will meet a performance need in the organisation. You cannot do this without the benefit of their experience and wisdom. Be 100% clear that your task is not to replicate the SME’s wisdom in every member of your target audience, just to make sure these people can do their jobs. It takes years, if not decades, to build true expertise. You may only have 30 minutes.

Perhaps the biggest barrier to you getting the project ready on schedule is the time it takes to get SME approval of your designs and scripts. This work is almost always underestimated, leading to all sorts of delays and disruptions. It’s best to spell out quite clearly when you will require SME time and for how long. Show the SME a typical design document or script so they know what to expect. Explain that approvals, while perhaps not completely binding, will be regarded as permission to proceed with the next stage of the project. Changes can still be made, but only with a corresponding risk to the schedule and budget.

Don’t bore your SME with learning jargon. They will find this every bit as impenetratable and uninteresting as you (and your target population) may well find their subject expertise. But using plain English isn’t the same as acting dumb. You have a duty as a professional to make clear how it is that adults learn best. Surprisingly, this isn’t common sense. If it was, why are so many learning experiences no more than a knowledge dump. Explain how hard it is to engage the learner, to get them to focus enough on an idea to hold it in long-term memory and then be able to retrieve this learning when it really matters – doing the job. Transmitting information is the easy bit – your job of making it stick is really hard.

Back to: Part 1

Coming in part 3: Asking the right questions

First published in Inside Learning Technologies, November 2011