![]()

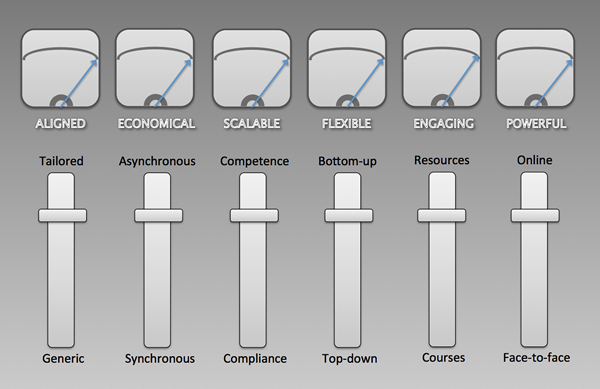

In this series of posts, I explore six ways in which learning professionals can realise a transformation in the way that learning and development occurs in their organisations. It builds on the series I posted earlier in the year, in which I set out the six major elements in a vision for change, i.e. learning that is aligned, economical, scalable, flexible, engaging and powerful.

The sixth and last step on the route to transformation is a shift from delivering learning face-to-face to delivery online. There are obvious benefits from learning online in terms of flexibility, as well as savings in terms of time, budget and emissions, but old habits die hard and many learning professionals are finding it hard to make the change.

Of course, not all learning can be brought online while maintaining quality, for example:

- Some interpersonal skills courses require tutors and/or participants to be able to accurately monitor the body language of others.

- Some practical courses require students to interact with equipment in ways that cannot feasibly be simulated online.

- Some courses benefit from the opportunities provided for networking socially.

- Some skills are more authentically practised in the real job environment.

But, as a whole, we tend to exaggerate the extent to which our face-to-face events really need to remain that way. It is worth reflecting on how we consume media in our personal lives. Of the music we listen to, only a small proportion is in a club or concert hall. Of the drama we consume, most is on the TV or in the cinema, not the theatre. Of the sport we watch, the overwhelming majority is on TV. When we do go to a theatre, concert hall or sports stadium, it is a very special event, often one we will remember for a very long time. But for most of us, this is not normal practice.

The benefits

So what effect does pushing the slider from face-to-face to online have on the six elements of our transformation vision?

Aligned: No real impact here.

Economical: There are obvious benefits here, as time and money is saved by removing the need for travel. Learning time also tends to reduce, because there is less of a temptation for course designers to fill a whole day or week with training when the time is not strictly needed.

Scalable: Face-to-face events are constrained in terms of scalability because of the practical limitation of space. Eighty thousand people may have been able to watch the 100m final at the Olympics in London, but hundreds of millions could watch remotely, not only on TV but online. As the providers of massively open online courses have discovered, while a lecture room might be packed to capacity with 100 students, a thousand times more could take part in an online lecture.

Flexible: Online learning is, above all, more flexible because it frees the learner from the constraints of geography. An online learner can access what learning they want, wherever they want, without the time, financial and environmental costs of travel.

Engaging: There is no reason why an online experience should necessarily be less engaging than one which is face-to-face, assuming it is relevant and well-designed, but there is still a certain magic about ‘being there,’ particularly when the opportunities are scarce, e.g. the big game, the farewell tour, the invited audience. You will never quite be able to match this experience in a live online event, but whether this really matters in a learning and development context is debatable.

Powerful: No reason why there should be an impact here.

In summary

If you push the faders on all six strategies, you can maximise every element of your vision, as you can see from the ‘mixer’ below. While some of the strategies have positive and negative consequences, when used in combination the pluses greatly outweigh the minuses and allow you to achieve all your goals.

Coming next: The steps needed to achieve transformation

Looking back: 1. From generic to tailored / 2. From synchronous to asynchronous / 3. From compliance to competence / 4. From top-down to bottom-up / 5. From courses to resources