![]()

Skills matter a great deal more at work than knowledge. Skills are the abilities to do things, to put knowledge into practice. As such, they directly impact on performance. There is really only one way to acquire skills and that is through practice, ideally with the aid of specific, timely and relevant feedback. If there is one consistent fault with the training programmes that most organisations provide, it is an over-emphasis on theoretical knowledge and a wholly inadequate provision for practice with feedback. By far the most successful training technique is to provide just the most essential information up-front and then to get the learner practising. You can feed in more ‘nice to know’ information as the learner begins to build confidence.

From the point of view of designing blended solutions, what really makes the most difference is to determine the type of skill that needs developing. To inform your choice of methods, it helps to make the distinction between rule-based tasks and principle-based tasks.

Rule-based tasks are algorithmic and repetitive. As long as you follow the rules, you’ll get the job done to a consistent quality. These are tasks like replacing a punctured tyre, completing a form or operating a cash register. You can teach these tasks using simple instruction – learn the rules, watch me doing it, then have a go yourself.

The trouble is that less and less of the tasks we have to perform at work are rule-based. After all, if they were that algorithmic, it would have been very tempting to get a robot or a computer to do them, or to move them off-shore. More of the work we do in the developed world is heuristic – it requires us to make judgements based on principles. Principles are not black and white – they need to be experienced rather than taught. As we shall see later, with principle-based tasks, we’re much better off using a strategy of guided discovery.

There is another way to analyse skills, which will help us when we come to make decisions about delivery media. This time we’re making a different distinction: when the learner applies this skill, with whom or with what will they be interacting?

Motor skills: In this case the learner is interacting with the physical world; for example, lifting a heavy object, driving a car, using a mouse. While these tasks can sometimes be simulated, as with flying a plane, more often than not we have to provide opportunities for practice with the real object in a realistic situation.

Interpersonal skills: Here the learner is interacting with people, as they would if they were making a sale, providing someone with feedback or making a presentation. Again, interpersonal tasks can be simulated, but no computer can accurately provide feedback on a learner’s performance. We’re going to have to provide opportunities for practice with other people.

Cognitive skills: In this case the learner is interacting with information. Lots of our tasks at work are like this, requiring us to solve problems and make decisions. Examples include business planning, using software, solving quadratic equations, writing reports, or reviewing financial data. Cognitive skills lend themselves more easily to computer-based practice.

Of course, you’re quite likely to find there’s a need for a mix of different skills – rule-based and principle-based, motor, interpersonal and cognitive. This is another powerful reason why blended learning can be so useful – there simply isn’t one method or medium that meets the whole need.

Next up: When the need is to shift attitudes

Author: Clive Shepherd

3. When the need is for knowledge and information

![]()

Knowledge and information are not quite the same thing. Knowledge is information that has been stored in memory, so it can be referenced without the need to refer to some external resource. This is an important distinction when you’re analysing requirements. It’s essential you find out what really needs to be remembered and what can be safely looked up as and when needed. There is a definite change in people’s expectations in this respect, because it has become so easy to search online on a PC or a mobile device that it seems pointless to try and remember all the information that’s relevant to your job. You’ll want to pick out those items of information that someone really must know if they are to perform effectively in their job. The rest you can provide as a resource.

Perhaps the greatest danger when analysing requirements is to over-estimate the amount of knowledge that people are going to need. The main culprits are subject experts who have long since forgotten what it’s like to be novices in their particular fields and think just about everything that they know will be interesting to learners and is important for them to know. A good way to resist this is to ask the question: “What’s the absolute minimum that learners need to know before they can start practising this task?” Again, this keeps the focus on performance.

Next up: When the need is for skills

2. Introducing the three L’s

![]()

I’m going to start with the first step in the process – analysing the situation. We do this first because the information we uncover at this stage underpins just about every decision we make when it comes to design. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that the most appropriate design can seem pretty obvious once you have the right information at your disposal.

Situation analysis has three elements, which can be described quite simply as the three L’s – the learning, the learners and the logistics. In the next few posts I’m going to concentrate on the learning. I’ll move on to handle learners and logistics.

By ‘the learning’ I mean the end point that we’re aiming towards with our solution. Be careful, because while learning may be our aim, our ‘client’ is probably much more concerned with what this learning might achieve in terms of increased performance. If we can focus in on performance, then this will serve us well when we come to making design decisions.

We cannot always take a requirement for a learning solution at face value. Our client may be wrongly diagnosing the problem. Work performance is influenced by objectives, organisation structure, available resources, working conditions, incentives and disincentives, aptitudes, motivation and the quality of feedback. None of these are going to be fixed through a learning intervention. Our job starts when there is a shortfall in knowledge (and information), skills and attitudes.

Next up: When the need is for knowledge and information

1. Getting started with blended solutions

![]()

The concept of blended learning may seem to you a little ‘old hat’ for 2013. After all, people have been blending learning methods and media for as long as there have been things people need to learn and others willing to teach them. Yet somehow, it is only in the last couple of years that the modern learning and development professional has fully comes to terms with the fact that a single approach – a classroom course, perhaps, or an e-learning module, or a period of on-job instruction – when used on its own, is rarely capable of completely satisfying a learning objective.

Blended learning is right now the strategy of choice for most major employers, whether or not that is how they describe it. The blended learning of 2013 is broad in scope, extending well beyond formal courses to include all sorts of online business communications, from webinars to videos. Increasingly, social and collaborative learning is also incorporated into the mix, as well as performance support materials, and opportunities for accelerated on-job learning.

Employers recognise that learning at work takes place continuously, whether or not it is formally planned. They understand that courses are not enough to change behaviour and increase performance. As a result, they increasingly expect more far-reaching solutions that go well beyond the presentation of information and half-hearted attempts at providing opportunities for practice. They want learning solutions that deliver and that places fresh demands on the designers of those solutions.

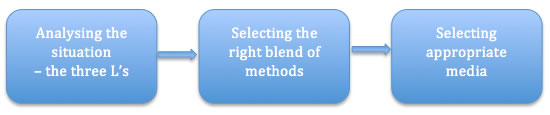

In this series of 20 short posts, I explore what I believe to be the most important elements in a systematic approach to the design of effective and efficient blended solutions: analysing the unique characteristics of the situation for which the solution is being designed; selecting the right blend of methods to meet the needs of the situation; and determining the delivery media best suited to those methods. This might sound abstract and theoretical, but stick with me, because the process can be quickly and easily applied in practice.

Next up: Introducing the three Ls

Transformation: in conclusion

![]()

In this series of posts, running throughout 2012, I have endeavoured to explain Onlignment’s ideas for a transformation in workplace learning and development. These are the ideas that shape our thinking and which we look to apply in all our client engagements.

I started the series by setting out the need for transformation.

I then set out a vision for workplace learning and development that is:

I moved on to look at some of the changes that can be made to realise this vision, expressed as six shifts:

- from generic to tailored

- from synchronous to asynchronous

- from compliance to competence

- from top-down to bottom-up

- from courses to resources

- from face-to-face to online

In the posts that followed, I brought the series to a conclusion by focusing on the practical steps we can take to make transformation happen:

- Recognising the uniqueness of your particular organisation in terms of its requirements, the characteristics of its people and the constraints which govern its decision making.

- Establishing a learning architecture and infrastructure that recognises these unique characteristics.

- Putting in place processes for improved performance needs analysis and blended solution design.

- Building capability in areas such as the design of digital learning content, learning live and online, and connected online learning

I hope you have found the series interesting and, above all, useful in your work.

As a summary of the principal ideas, you might like to watch this video:

Making transformation happen: building 21st century learning skills

![]()

In this series of posts I’ve set out a vision and strategies for transformation in workplace learning and development. I showed how this process must be clearly aligned to an organisation’s particular learning requirements (‘learning’), the characteristics of its people (‘learners’) and the constraints which govern its decision making (‘logistics’). The ‘three Ls’ inform and shape our transformation process starting with the creation of an overall learning architecture and a supportive infrastructure, and moving on, as I explained in my previous post, to include processes for performance needs analysis and blended solution design.

The final stage in the transformation process – and outer layer of the transformation wheel (see below) – is the development of the new skills required of the 21st century learning professional:

Thirty years ago, when a new teacher or trainer entered the profession, they would have a relatively easy task to familiarise themselves with the learning media then available: flip charts, whiteboards, overhead projectors, perhaps an early VHS player. It was achievable to learn how to use all these media, so everyone did. As the years have gone by, the pace of change has accelerated until now it seems that every year there is a slew of new technologies fighting for our attention. Quite simply, there’s now a major skills gap with many learning professionals inadequately equipped to use the latest tools of their trade. This may be because they have not been provided with adequate opportunities to acquire the necessary skills; in some cases it could also be a case of burying your head in the sand.

Creating digital learning content

Digital learning content takes a wide variety of forms, including tutorials, scenarios, podcasts, screencasts, videos, slideshows, quizzes and reference materials. In fact we are fast approaching a point at which all learning content will be digital and online.

The skills of digital learning content design are relevant to anyone with an interest in helping others to learn, whether that’s a teacher, trainer, lecturer or coach, a subject expert with knowledge they want to share, or an experienced practitioner who wants to pass on their tips.

Some will dedicate themselves to content design as their full-time speciality, but every learning professional should know the basics, just as in the past everyone would have been able to deliver a half-decent training session in a classroom.

Clive Shepherd’s book Digital learning content: A designer’s guide was published by Onlignment in 2012.

Delivering live online learning

Virtual classrooms provide a fantastic opportunity for any organisation that wants to get more training done more cheaply, particularly when participants are widely dispersed. Many of the skills of the classroom trainer can be transferred without difficulty to an online setting, but the experience can still be strange and sometimes a little daunting for those starting off as virtual classroom facilitators. Although formal training can be helpful, the main emphasis should probably be placed on lots of practice with the help of a good coach.

Live online learning: A facilitator’s guide was published by Onlignment in 2010.

Facilitating connected learning

Since the advent of social media, hundreds of millions of people have been able to build and sustain their personal networks online. The emergence of smart phones and tablets has accelerated this trend by allowing us to stay connected wherever we are and at any time of day. Unsurprisingly, there is keen interest in bringing these advantages to the world of work, with obvious benefits in terms of learning and performance support.

Connected learning takes advantage of online networks and simple collaborative tools such as forums, wikis, blogs and social networks. It has its place in formal learning, within new blends that extend well beyond the classroom. But its major benefits will occur informally, as a means for on-going support and collaboration.

In some cases, learning professionals can just sit back and allow connected learning to occur naturally on a peer-to-peer basis, but there are situations where their skills in facilitation and coaching could prove really valuable. And novices will appreciate their help as curators who identify useful resources and put people in touch with others who can help them. But before they can do this, learning professionals must themselves become connected.

Coming next: A conclusion to the series

Making transformation happen: analysis and design

![]()

In this series of posts I’ve set out a vision and strategies for transformation in workplace learning and development. I showed how this process must be clearly aligned to an organisation’s learning requirements, the characteristics of its people and the constraints which govern its decision making. These factors inform and shape our transformation process starting, as I explained in my previous post, with the overall learning architecture and the creation of a supportive infrastructure.

Architecture and infrastructure form the inner layers of our transformation wheel. We need to build on these by establishing new policies for performance needs analysis and blended solution design:

Performance needs analysis

An effective needs analysis process identifies gaps in performance which can be realistically addressed by learning interventions. It aligns these interventions with business needs and ensures that the right people are trained at the right time, in the right way and to the right extent.

That’s the theory. In practice a lot can go wrong, for example:

- You fail to understand the underlying performance issue, making it harder to establish goals or evaluate results.

- You jump to the conclusion that training is the right solution, when in practice there is no underlying problem knowledge or skills.

- You misunderstand the nature of the learning requirement and, as a result, make inappropriate design decisions.

- You fail to clarify the exact nature and composition of the audience, with the risk that the wrong people are targeted and efforts misplaced.

- You don’t get a handle on the logistical constraints, with the danger that your solution will fail to meet your client’s needs.

Blended solution design

It’s hard to achieve the outcomes and the efficiencies you require using a single learning method or medium. Today’s most powerful and scalable solutions employ a careful mix of social contexts (learning alone, one-to-one or in a group) and exploit the latest technologies. Making choices which satisfy the three Ls (the learning, the learner and the logistics) for the particular situation requires skill and balance.

We may consider ourselves lucky to have so many new choices in terms of learning technologies, and so many ways of combining these with traditional approaches. Unfortunately, what tends to happen is that, when we’re faced with a huge range of options, we revert to the old familiar solutions. In other words, we carry on doing what we’ve always done. If we’re more adventurous there’s another danger – that we follow the trends and look for ways to innovate at all costs. We have a bundle of solutions and we’re desperate to find problems to match.

Again, the answer is a simple and logical process for making decisions on learning strategies and delivery media; one that looks first and foremost to meet the client’s performance objectives, but which also delivers in terms of the efficiencies all organisations are demanding.

Clive Shepherd’s The Blended Learning Cookbook was published in 2008. It outlines a process for the design of blended solutions that is used by many hundreds of learning professionals. A third edition is planned for 2013.

Coming next: Building the skills of the 21st century learning professional

Making transformation happen: learning architecture and infrastructure

![]()

In this series of posts I’ve set out a vision and strategies for transformation in workplace learning and development. In the previous post, I showed how this process must be clearly aligned to an organisation’s particular learning requirements (‘learning’), the characteristics of its people (‘learners’) and the constraints which govern its decision making (‘logistics’). The ‘three Ls’ inform and shape our transformation process, starting with the overall learning architecture and the creation of a supportive infrastructure:

Learning architecture

We are all learning machines, constantly adapting to the ever-changing threats and opportunities with which we are confronted. We learn through experience, whether consciously or unconsciously; we learn by seeking out the knowledge and skills we need to carry out our day-to-day tasks; we learn by sharing experiences and best practice with our colleagues, and by taking advantage of opportunities for development, both formal and informal.

The learning architect designs environments that enable specific target populations to take maximum advantage of all these opportunities for learning. To do this they need to understand the unique characteristics of their clients and the business challenges they are facing; they need to find just the right balance between top-down and bottom-up learning initiatives, between the formal and informal.

A learning architecture provides a blueprint for a working environment that supports and encourages learning. Just like the plans for a building, it looks to the long term, providing strength and stability while also providing plenty of scope for adaptation as needs change.

Clive Shepherd’s book The New Learning Architect was published by Onlignment in 2011.

Learning infrastructure

An architect’s plans go well beyond a specification for materials and dimensions; they also have to take account of the systems that need to be in place for the building to fulfil its purpose – the electrics, plumbing, lighting, security and so on. Similarly a learning architecture is just the starting point. To function properly, careful thought needs to be given to the learning infrastructure:

- the computing devices available to employees, whether desktop, laptop or handheld;

- the networks linking these devices;

- the tools provided to support communication and collaboration, including intranets and extranets, social networks, email, instant messaging, web conferencing systems, forums, blogs and wikis;

- tools to support the orderly management of documents and other forms of digital content;

- tools that allow for quick access to information on-demand;

- tools to track learning where this is required for compliance purposes;

- tools, equipment and facilities for creating digital learning content.

Thought must also be given to the governance of organisational learning, bringing together learning professionals, senior managers and representative learners to review and approve strategic plans and to monitor progress. And implementing this strategy is likely to demand a rethink of the way in which l&d responsibilities are organised and distributed throughout the organisation.

The inner core

Architecture and infrastructure form the inner core of our transformation wheel:

In coming posts, we will continue to add layers of detail, starting with the processes that need to be put in place for improved performance needs analysis and blended solution design.

Coming next: A process for analysis and design

Making transformation happen: how organisations differ

![]()

So far in this series of posts, I’ve set out a vision and strategies for transformation in workplace learning and development as they would apply to some generic organisation. Needless to say, that organisation only exists in abstract. If you’ve been following the series, then hopefully you’ll have bought into some of the ideas (otherwise why would you still be reading?), but you’ll also probably have encountered recommendations which make little or no sense in the environment in which you work. Clearly every organisation needs its own vision and strategy for transformation, shaped around its own unique characteristics.

So what are the characteristics that make the most difference? In our experience, they can be summarised under three headings: the requirements in terms of learning, the characteristics of the employee population, and the particular opportunities and constraints that shape decision making. My colleague, Phil Green, calls these the three Ls – learning, learners and logistics.

Learning

Each organisation (and each department, division and horizontal slice within this) has particular requirements for learning. Strictly speaking these requirements are actually for improved performance because, unless the organisation is a school or college, it is only indirectly measured in terms of the learning it manages to bring about. And if, as learning professionals, we focus our efforts on improving performance, then we have to take a broad view of what ‘learning’ actually encompasses. Increasingly it is not just learning (evidenced as knowledge, skill or attitude) that is required to support performance, but access to just-in-time information. This cannot strictly be regarded as learning, because the information just needs to be used rather than memorised, but that does not diminish its importance in our overall strategy for transformation.

An organisation’s requirements for learning (and just-in-time information) should be directly aligned to its goals and strategy (if you remember, in an earlier post, I presented alignment as one of the six key elements in our vision for a transformed l&d). An organisation’s requirements are likely to be many and varied, but one or more of the following types of learning is likely to be of particular importance:

- Understanding and committing to the organisation’s mission, values, policies and strategies.

- Understanding the organisation’s work processes.

- Keeping up-to-date with inevitable changes and developments in what we need to know and be able to do.

- Performing routine administrative tasks.

- Solving problems and making judgements.

- Communicating using electronic media.

- Interacting person-to-person with peers, direct reports, customers, suppliers and other third parties.

- Interacting with the physical world, with vehicles and with equipment.

You will undoubtedly think of more examples. These distinctions matter because each type of learning demands a different approach. It addresses a different form of knowledge, skill or attitude and impacts, therefore, on the extent to which you will want to make the six strategic shifts described in earlier posts. For example, in some organisations the prime consideration may be to keep its highly-educated professional workforce up-to-date with technological developments. This is going to support the shifts from synchronous to asynchronous, from courses to resources, from top-down to bottom-up and from face-to-face to online. For another organisation, a critical determinant of success may be the way they interact with their customers, as it would be in a retail environment. In this case the shifts away from traditional approaches will still be relevant, but are likely to be more measured, with a continuing reliance on face-to-face learning.

Learners

The second major way in which organisations differ is in the characteristics of their employees. Each of the following is going to have an impact on which sliders you push, how far and how fast:

- Their prior knowledge.

- Their motivation to learn.

- Their confidence in using new technologies.

- Their expectations in terms of learning at work.

- Their independence as learners.

- The discretion they have over how they allocate their time.

- How long they tend to stay in the job.

Logistics

All decisions are made within the context of constraints and opportunities. Any of the following could make an important difference to your l&d strategy:

- The attitudes and opinions of senior managers.

- The availability of funds to support learning.

- The speed with which the organisation must respond to change.

- The availability of the necessary hardware, software and bandwidth.

- The size of the organisation.

- The geographic dispersion of employees.

Again, you will undoubtedly be able to add to this list.

Without a clear and detailed knowledge of the three Ls, it will be difficult to come up with a strategy for transforming l&d which will really work. If you are unprepared and ill-informed, there is a danger your efforts at change will be rejected as inappropriate or ahead of their time. If you tailor your transformation strategy to the needs of the organisation, you could find you are pushing against an open door.

Coming next: Putting in place a learning architecture and infrastructure

Transformation: Making it happen

![]()

In this series of posts, running throughout 2012, I have endeavoured to explain Onlignment’s ideas for a transformation in workplace learning and development. These are the ideas that shape our thinking and which we look to apply in all our client engagements.

I started the series by setting out the need for transformation.

I then set out a vision for workplace learning and development that is:

I moved on to look at some of the changes that can be made to realise this vision, expressed as six shifts:

- from generic to tailored

- from synchronous to asynchronous

- from compliance to competence

- from top-down to bottom-up

- from courses to resources

- from face-to-face to online

In the posts that follow over the next few months, I will bring the series to a conclusion by focusing on the practical steps that we can take to make transformation happen:

- Recognising the uniqueness of your particular organisation in terms of its requirements, the characteristics of its people and the constraints which govern its decision making.

- Establishing a learning architecture and infrastructure that recognises these unique characteristics.

- Putting in place processes for improved performance needs analysis and blended solution design.

- Building capability in areas such as the design of digital learning content, learning live and online, and connected online learning.

Coming next: How organisations differ