![]() In the first part of this practical guide, we reviewed the capabilities of, and applications for, packaged slide presentations as a tool for learning. In this second installment, we look in more detail at the visual element in the presentation – the slides. Next time we’ll examine the best ways to go about recording a narration.

In the first part of this practical guide, we reviewed the capabilities of, and applications for, packaged slide presentations as a tool for learning. In this second installment, we look in more detail at the visual element in the presentation – the slides. Next time we’ll examine the best ways to go about recording a narration.

What your slides must achieve

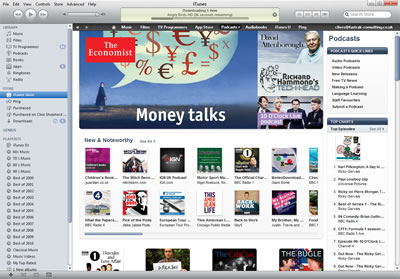

If your slide show is going to be packaged with an audio narration, then your slides have very much the same function as they would do in a live presentation – they convey the visual element, while a voice delivers the words. In this context, slides are visual aids. With photographs, illustrations, diagrams and charts, they capture the viewer’s attention, clarify meaning and improve retention. With the sparing use of on-screen text, they can also help to reinforce key elements of the verbal content, but the prime purpose is always visual.

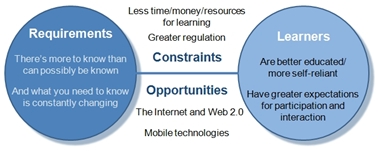

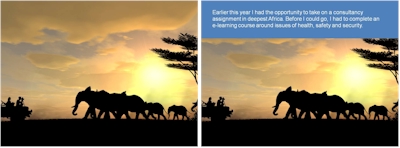

Without narration, your slides have to accomplish both roles – the visual and the verbal. In this respect they need a very different design focus to a live presentation. Take the following example of a slide taken from a live presentation that was converted to stand alone, without narration, on slideshare.net. A section of the slide has been allocated to a running textual commentary, essentially a much simplified version of the original presenter’s words:

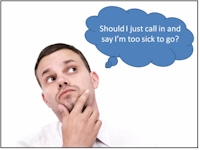

Not that this is the only way of displaying the verbal content. If, rather than converting a live presentation, you were designing a stand-alone and un-narrated slide show from scratch, you could use all sorts of devices to display the words, like the speech bubbles used in this example:

Another consideration is the distance from which your slides will be viewed. In a live presentation, your audience is likely to be some way from the screen, whereas when the slides are used for self-study, they will be up close. Whether this matters depends on the device the audience will be using to view the presentation (this could be anything from a smart phone to a large PC monitor) and the size of the window in which your presentation will be displayed. You may be able to get away with displaying more detail than you would when live, but this needs testing.

An argument for imagery

Only an expert wordsmith can conjure up with words what a person, object or event actually looks like. Only an expert teacher can explain a concept or process clearly using words alone. And only a wonderful presenter can make a lasting impact on an audience without the use of imagery. As the saying goes, “a picture is worth ten thousand words”. Pictures show, quite effortlessly, what things really look like. They clarify concepts and processes. They stick in the memory. All you have to do is use them.

Pictures come in a variety of forms to suit different situations. Photographs portray what things look like; diagrams clarify concepts and processes; illustrations make the abstract more memorable. Presentation software such as PowerPoint makes it easy to employ pictures in all these forms. Your task is to avoid the lazy option – clip art – and to find the picture that really does tell a story.

Break the mould

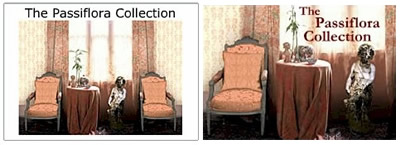

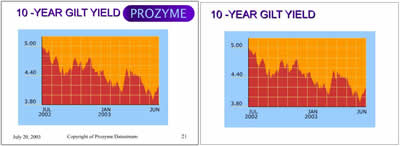

It’s all too simple to use the standard templates provided by your presentation software, but these won’t always do justice to your images. Take these two examples:

You can definitely do without the slide junk – the logos, headers and footers that appear on every slide. There’s a place for your logo and that’s on the title slide (OK and maybe at the end as well). And you don’t really need all that clutter at the bottom of each slide – you’re producing slides, remember, not a report.

Text is also OK in moderation

You’ve probably heard of the expression “death by PowerPoint”. You’ve probably experienced it.

Yes, we’ve all been there, and yet we put up with it – see The Emperor’s New Slide Show.

Well, by far the biggest complaint you will hear from presentation audiences is that the slides contain too much text. In his book The Great Presentation Scandal, John Townsend relates how he counted the number of words and figures on every slide at a conference he was attending. The overall average was 76. That’s right, 76.

Given this, you may find it surprising that we could be recommending the use of text as a visual aid when the real problem is that there’s far too much of it. This is a fair point, but text can be useful as a visual aid, when you need to highlight the start of a new section, emphasise a key point, list a number of related points or present data in the form of a table.

If you do keep the amount of text on your slides to a minimum, it will have that much more impact when it does appear; particularly if you know when to use it and how to lay it out like the professionals. If you obey a few simple guidelines, that’s what you will achieve.

Use your slides to tell a story

A presentation is much more than a collection of independent thoughts accompanied by visual aids – however interesting the thoughts and however brilliant the visuals. Just like a novel, a radio play or a film, it has a beginning, an end and a carefully planned route in between.

Too many presentations look like they have been constructed by simply extracting slides from previous presentations. Although re-using slides is fine, if they are appropriate to the task in hand, this is never going to be enough to do the job. Like a film director, you have to look at the big picture, using words and images to manipulate your audience’s attention and their emotions. There is no black art to this; you just need a little imagination and a simple structure.

Coming next: the narration