![]() In part 1 of this series, we looked at what a learning scenario is, its basic structure, capabilities and applications. In part 2 we saw how simple scenarios could be used to help learners to undertake principle-based tasks. In part 3 we looked at how you could use simple scenarios to help learners to practise rule-based tasks. In this final part, we turn our attention to branching scenarios, which provide a more immersive approach to learning principle-based tasks. This builds on what we covered in part 2, so you might want to check back on that first. Our focus us here is on what it means for a scenario to be branching.

In part 1 of this series, we looked at what a learning scenario is, its basic structure, capabilities and applications. In part 2 we saw how simple scenarios could be used to help learners to undertake principle-based tasks. In part 3 we looked at how you could use simple scenarios to help learners to practise rule-based tasks. In this final part, we turn our attention to branching scenarios, which provide a more immersive approach to learning principle-based tasks. This builds on what we covered in part 2, so you might want to check back on that first. Our focus us here is on what it means for a scenario to be branching.

Why branching?

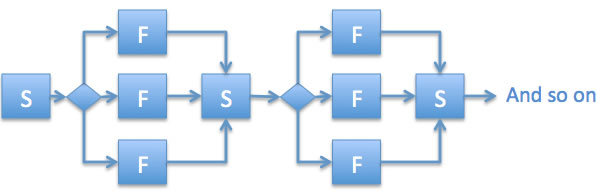

To understand the value of branching, you first need to understand how a scenario looks when it doesn’t branch:

The diagram shows the learner being presented with a situation (S) and three choices. The learner is then immediately provided with feedback (F), related directly to the choice that they have made, pointing out positive aspects and correcting any misunderstandings or errors. All learners then proceed to the second stage of the scenario. Although the feedback can be considered to be branching, the overall path is linear.

While a linear scenario works well it many situations, it doesn’t resemble real life, where you get to experience the results of your decisions, for better or for worse.

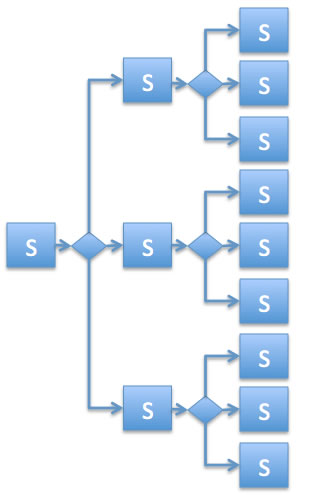

With a branching scenario, it will be possible for different learners to progress along different routes through the scenario and to experience different end points. Where you arrive depends on the decisions you make along the way.

The diagram shows only the initial two stages in the scenario – there could, of course, be many more. As you can imagine, if at every stage the scenario trebled in size (assuming three choices) it would soon become unmanageable. In practice, many branching scenarios return to a common narrative at key points or kick the learner out early if their initial choices represent fatal mistakes.

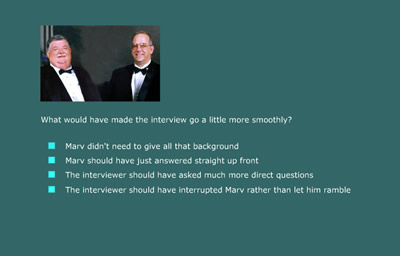

Providing the learner with feedback

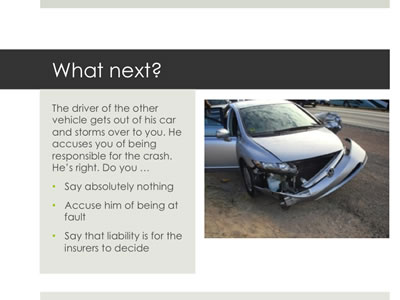

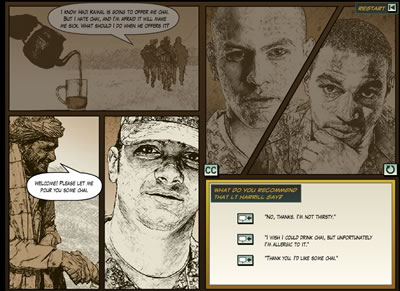

Looking at the second flow chart above, you might wonder where all the feedback went! Well, first and foremost, feedback is implicit in the branching that occurs. If you shouted at the customer in situation 1, you’ll get your payback in situation 2.

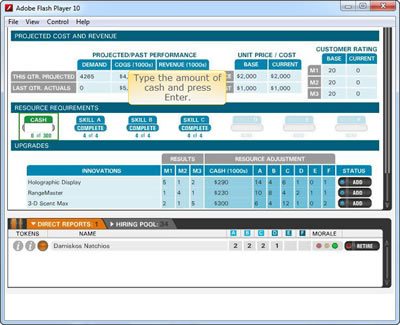

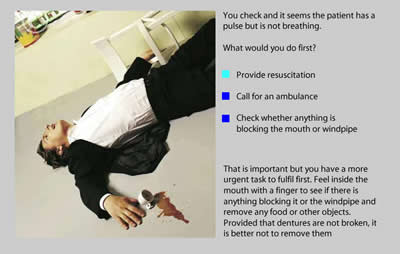

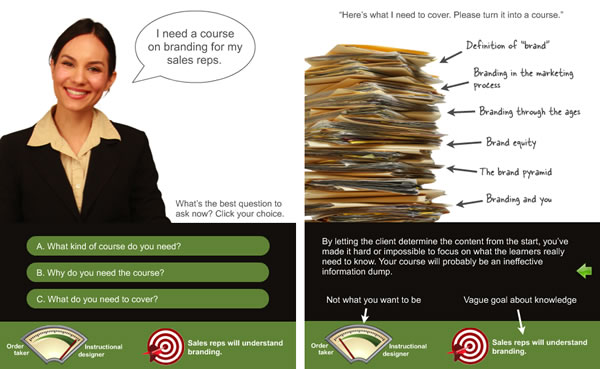

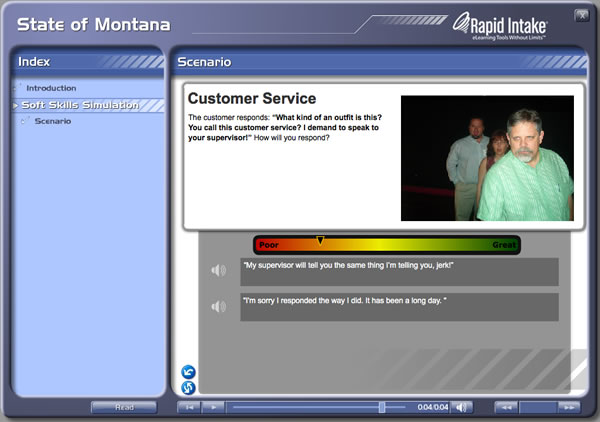

Another way that feedback can be provided is with some sort of visual indicator, as the following examples show:

Thanks to Cathy Moore for this one. You might also be interested in the flowchart that Cathy created to help her design and test this scenario.

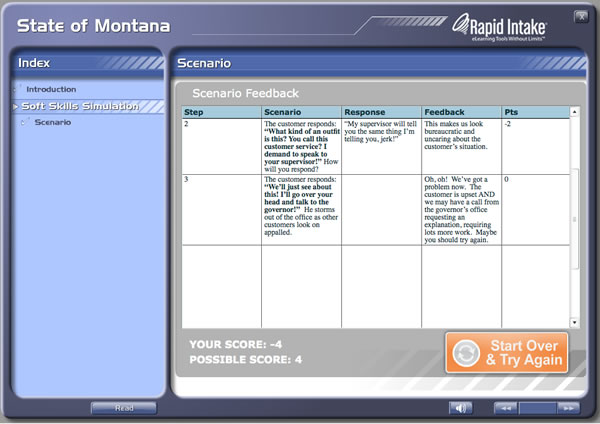

And thanks to Garin Hess at Rapid Intake for this example, which shows how comprehensive feedback can be provided at the end of the scenario.

Deciding on the look and feel

You can use any combination of still images, text, audio and video to present the situations in your scenarios, although the evidence is stacked against using text and speech simultaneously. Your decision is likely to be made on the basis of (1) how much realism is needed to adequately convey the situation, and (2) how much time and money you have got available to you.

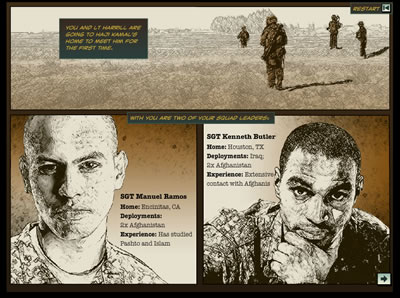

Cathy Moore, along with her friends at Kinection, turned to a comic book approach for the acclaimed Haji Kamal scenario:

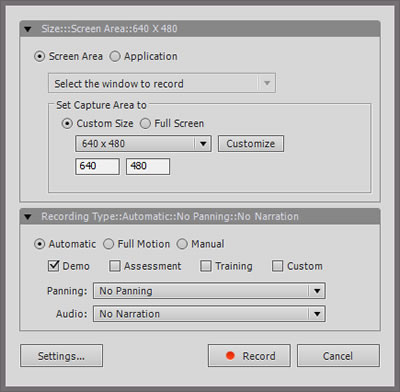

Tools for developing branching scenarios

It is perfectly possible to build simple branching scenarios in PowerPoint and then convert to Flash using a tool that supports branching such as Articulate Presenter. General purpose desktop authoring tools, such as Adobe Captivate and Lectora, or online tools such as Rapid Intake’s Unison, have all the functionality you need. There is also talk of Articulate having a specialist scenario-building tool, called Storyline, in the pipeline for later in 2011.

Enjoy your story-telling.

A PDF version of this Practical Guide is now available.

Next up in the series is a Practical Guide to producing learning videos.