![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 5:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the third part of chapter 5:

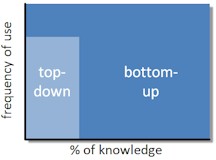

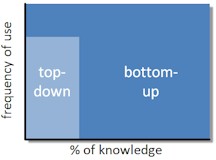

It’s possible that, where there isn’t that much to know and it doesn’t change that often, all learning can be managed on a top-down basis. However, this is completely unrealistic for the majority of organisations in which there’s far too much to know and it’s changing far too quickly. So where should the priorities be placed?

On the most critical knowledge and skills: Some learning is of high importance, not necessarily because it is required that often, but because if it is not applied on the occasions when it is required then there could be serious consequences for the organisation. Imagine a pilot who didn’t know how to land a plane in bad weather conditions, a financial trader who did not know how to respond to a market crash, a manager who did not realise the implications of firing a direct report who he happened not to like all that much. Some learning simply cannot be left to chance – it needs to be planned carefully, expertly facilitated and rigorously assessed.

On the most commonly-used knowledge and skills: Leaving aside the really critical, high stakes knowledge and skills, a judgement has to be made on how the remainder is handled. One answer is to apply the Pareto principle, also known as the 80:20 rule. This states that, in many situations in life, 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. In a learning context it would be reasonable to assume that 20% of all the knowledge related to a particular job will be adequate to cover 80% of tasks. The remaining 80% of the knowledge is used only occasionally. It makes sense, therefore, to concentrate resources on providing the knowledge that is most regularly needed, whether through a training intervention or the provision of performance support.

On novices: When you have little or no knowledge of a subject, you are more appreciative of a structured and supportive learning environment. Novice learners don’t have the advantage of existing schemas (generalised knowledge about situations and events) in long-term memory that enable more experienced employees to cope with less structured learning experiences. Clark, Nguyen and Sweller explain how carefully-designed instructional approaches “serve as schema substitutes for novice learners. Since novices don’t have relevant schemas, the instruction needs to serve the role that schemas in long-term memory would serve.” The implication of all this is that, if you’re a skilled l&d professional, your services will be most appreciated by novices.

Where metacognitive skills are low: Those with good metacognitive skills are better equipped to learn independently. They have a good feel for what they already know, what’s missing and how to go about filling the gap. They will benefit from top-down learning but they don’t depend on it. For this reason, where resources are tight, efforts are more sensibly directed at those who most need the assistance. There are various ways of finding out who has the ability to learn independently. You could (1) guess based on generalisations (unskilled workers, unlikely; software engineers, likely), (2) observe behaviour over time and come to a considered opinion, person by person, or (3) ask the people involved directly. Just make sure you don’t use the term ‘metacognitive skills’!

Coming next, the fourth part of chapter 5: Targeting top-down learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Author: Clive Shepherd

Why top-down learning is needed

Imagine a scenario where there were no top-down learning interventions, where there was no l&d department and no attempt at all by management to regulate and control the process of learning. Here’s what might happen:

- Employees naturally organise themselves so that, when new employees join the organisation, those with more experience show them the ropes.

- Employees take the initiative themselves to take on new responsibilities or swap responsibilities with others in order to further their development.

- Employees make an effort to share their expertise and experiences with each other.

- In the absence of internal expertise, employees explore what is available externally using their own networks of contacts, resources on the internet, print publications and professional associations.

Sounds good. On the other hand, this might also be the outcome:

- Everyone is so busy that, when a new employee joins, no-one has the time to spend with them.

- Where explanations are provided, the information is so unstructured that novices find it hard to assimilate.

- New employees don’t know what they don’t know, so they don’t ask the right questions.

- Learning is haphazard and critical information is often missed, resulting in accidents, costly mistakes and legal liabilities.

- When changes are made to policies and practices, the benefits are slow to be realised, because the changes are not properly understood.

- Employees are not provided with new challenges, so they get bored and leave.

- When expertise is not available, no-one knows what to do and managers must intervene to resolve the problem.

In simple terms, top-down learning is needed to control risk: the risk that employees won’t have the basic competences needed to carry out their jobs; the risk that employees will make costly or dangerous mistakes; the risk that change programmes will fail to meet their objectives; the risk that suitable candidates will not be available when positions become vacant. These are serious risks. Either an organisation has a great deal of trust in its employees to prevent these risks becoming a reality (which may be a sound judgement in exceptional cases), or it must take preventative action itself. And that’s a top-down approach.

Coming next, the third part of chapter 5: How much learning should be top-down?

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning videos: part 4

![]() In part 1 of this series we examined the potential for video as a learning tool. In part 2, we moved on to look at the steps involved in pre-production. Part 3 took us to the shoot. And so to the final stage in the creation of a learning video – post-production. At this stage we collect together all the material that we shot at the production stage, select what we want to keep and what we can safely leave ‘on the cutting room floor’, edit all this together, add titles, graphics, music and effects, export as a finished product and distribute to our audience. This may all seem very technical but modern software has transformed much of this to a process of drag and drop, copy and paste. So let’s get started.

In part 1 of this series we examined the potential for video as a learning tool. In part 2, we moved on to look at the steps involved in pre-production. Part 3 took us to the shoot. And so to the final stage in the creation of a learning video – post-production. At this stage we collect together all the material that we shot at the production stage, select what we want to keep and what we can safely leave ‘on the cutting room floor’, edit all this together, add titles, graphics, music and effects, export as a finished product and distribute to our audience. This may all seem very technical but modern software has transformed much of this to a process of drag and drop, copy and paste. So let’s get started.

Editing

Editing is not obligatory. There’s nothing to stop you shooting something straightforward like an interview to camera and then uploading the results, without modification, to a site such as YouTube. But even the simplest videos will usually benefit from a little editing, even if just to trim the start and finish points and add a caption to inform the viewer who it is that’s speaking. This sort of editing is a doddle. And while you’re at it, why not add a title, perhaps with a little music behind? Yes, before you know it, you’re putting together videos that, while not quite professional in quality, don’t annoy the viewer with their amateurishness.

The aim of editing is to be invisible. In other words, you want the viewer to be able to concentrate on the content of your video without becoming aware of any of the mechanics of production and post-production. If you’ve done a good job, no-one will say what a good job you’ve done of putting it all together – they’ll just thank you for a great piece of content.

Video editing software comes at three levels of sophistication: (1) the free programs that come with your computer, such as MovieMaker (Windows) or iMovie (Mac), (2) budget versions of the top-end tools, such as Adobe Premiere Elements (under $250) and (3) the top-end tools themselves, Final Cut Pro (Mac only), Adobe Premiere Pro and Sony Vegas Video Pro. Although you wouldn’t think so from the price tags, pretty well all video editing software is roughly the same. The free software will get you a long way and may be more than enough for all your future needs. If you love playing with software, you’ll want more features and the mid-level tools will provide you with plenty of toys. The top-end tools are for pros and if you’re one of them you won’t be reading this guide.

Your basic editing tasks are as follows:

- Import your clips from your camera.

- Choose the clips you want to use and drag and drop them onto the timeline.

- Where appropriate, split clips up into smaller clips.

- Trim the start and end point of each clip.

- Arrange the clips into sequence.

- A simple cut between clips is usually best, but in some cases you may want to create a transition, perhaps some form of cross-fade. If you want your editing to be invisible, then avoid flashy transitions.

- Overlay titles and captions where appropriate.

- You may want to cut away to photographic stills or graphics. By contrast with your video clips, these could look overly static, so consider adding movement through some subtle panning or zooming.

- To help create the right mood, consider adding a music track, particularly in those sections where there is no speech.

With a little practice, these tasks will be simple enough to perform. If you want more help, there are plenty of great how-to videos on YouTube – which only goes to emphasise what a great learning tool video can be. Look for inspiration on YouTube and on the TV. In particular, focus in on those programmes in which the editing is almost invisible and try to identify the techniques that were used to achieve that result.

Sharing

Now your video is ready to go, you’ll want to get it into the right format for your intended audience. You’ll probably want to distribute your video material in one of the following three ways:

- On a DVD: In this case your editing software will guide you through the steps needed to write a single disc or to prepare a disc image for duplication.

- As an element within an e-learning module: The key here is to find out what formats and resolutions are supported by your particular authoring tool. Obviously you’ll want your video to be played back in the largest video window and with the best audio quality possible, but check out whether your this will be realistic given the bandwidth available to your audience.

- Through a video streaming service such as YouTube: We all know how YouTube works and how well it adapts to the available bandwidth and the particular device you are using. You can upload to YouTube in quite a range of formats, but you should probably check out the most appropriate options on the YouTube site first. Your videos do not have to be made public – if you prefer you can restrict access only to those who are provided with the URL. Even so, if you need a completely secure service, YouTube may not be the answer. Check with your IT department or LMS provider to see what other options are available.

Don’t be too put off by the thought of the burden you will be placing on your organisation’s network by making video available online. Chances are your network is capable of supporting hundreds, perhaps even thousands of simultaneous users without undue strain. But do check first. You won’t be popular if business grinds to a halt as scores of employees rush to sample your latest offering.

That concludes this practical guide. Good luck!

This guide is now also available as a PDF download.

Coming next: Creating learning tutorials

A practical guide to creating learning videos: part 3

The ‘piece to camera’ or PTC

We’re all familiar with the piece to camera as a technique used in news broadcasts, but in the context of low-budget learning videos, we’re more likely to use this approach to record a response to a question. The following tips will help you to do an effective job:

- Explain to the subject what you are going to do and what question you would like them to answer.

- Make a note of the subject’s name and check the spelling with them before you leave.

- Find an interesting setting, ideally one which will reflect the context of the topic.

- Position the camera at the subject’s eye level, ideally on a tripod. Whatever you do, do not look down on the subject.

- Frame the shot so you don’t leave lots of space above the subject’s head as this will make them look short.

- Ask the subject to look directly into the lens.

- Don’t rehearse if you want the subject’s response to sound really natural.

- If you’re feeling adventurous, add some movement by using an occasional slow zoom in and out.

The interview

The interview is one of the principle video formats and one that has real value for learning. In the ideal world you would shoot an interview with two cameras – one for the interviewer and one for the interviewee – and then choose the shots you would like to go with during the edit. However, this series is about what you can do with very little equipment and very little experience, so let’s see what you can do with a single camera.

If you want to keep it simple, frame your shot to include both the interviewer and interviewee (see above). If at all possible you should use an external mic, which the interviewer can hold.

It’s also possible to simulate a two-camera shoot and this will certainly provide you with a more interesting end result, particularly if the interview is extended. You’ll need to set up at a number of different angles:

- A shot which shows both the interviewer and interviewee (a ‘two-shot’), to establish the scene and prove that this interview really did happen with both parties present at the same time! Sometimes this is shot over the interviewer’s shoulder (an ‘OTS’).

- Close-ups of the interviewee listening to the questions (which are being spoken off camera) and then giving their answers.

- Reverse shots of the interviewer listening intently to the responses (usually called ‘noddies’). These can be useful in covering up any cuts you want to make in the interviewee’s answers.

- Reverse shots of the interviewer asking the questions. Be clear that, because you have only one camera and mic, these are recorded separately from the interviewee’s answers – you can safely ditch the original questions to which the interviewee responded.

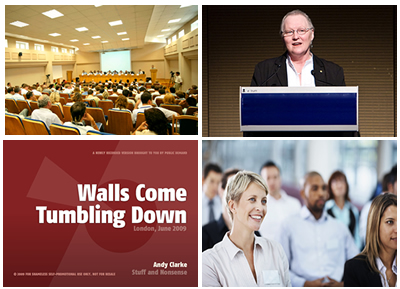

The presentation

A video recording of a lecture or presentation is an invaluable way to extend the reach beyond the initial face-to-face audience. Your simplest option is to record the presenter and any slides in one mid-shot. The camera will need to be on a tripod for stability. If the presenter is using a mic then your best best is to take a feed from this directly. If not, you’ll need to provide your own, ideally a radio mic that the presenter can attach to their shirt. Don’t rely on the mic built into your camera as you’ll be too far away from the presenter to get a clear signal.

If you don’t mind doing a little editing later, then you could mix up the shots …

A wide ‘establishing’ shot of the meeting room will set the scene. Then cut between a close up of the presenter and his or her slides. Don’t shoot the slides at the time – get a copy of the presentation, save each slide off as an image and then import these directly into the edit. You might also like to get some cut-aways of the audience to provide more visual interest.

Coming up in the thrilling final instalment: post-production

The scope of top-down learning

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 5:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 5:

Top-down learning occurs because organisations want their employees to perform effectively and efficiently and because they appreciate that this depends, at least in part, on these employees possessing the appropriate knowledge and skills. Top-down learning is designed to fulfil the employer’s objectives for improved performance, not the employees’.

Top-down learning occurs in all four contexts:

Experiential: Employers can initiate all sorts of programmes to maximise the opportunities for employees to learn directly from their work experience. For example, through a process of job rotation, employees might be moved from one position to another, perhaps from one geographical location to another, in order to obtain a more rounded perspective on the organisation’s activities. Similarly, through job enrichment, employees may be assigned additional responsibilities which expand their opportunities to develop. Other initiatives may attempt to institutionalise the process of reflection upon which experiential learning depends – formal project reviews, benchmarking within and between organisations, action learning programmes and, of course, performance appraisal.

On-demand: Where the nature of the work that employees carry out requires that they have ready access to information at the point of need, there are again many opportunities for top-down interventions. These include the provision of performance support materials, in print form or online, at the desktop or through mobile devices; employers may offer online access to vast catalogues of books, using services such as Books 24×7; they may also make available person-to-person support using help desks and other ways to ‘ask-the-expert’.

Non-formal: Of course nearly all employees will require some training to help them adjust to the organisation and to their new positions, to cope with changes and to prepare for future responsibilities. Proactive, top-down interventions include on-job training, coaching programmes and ‘mini-courses’ in various forms including short workshops, rapid e-learning modules, podcasts or white papers.

Formal: Top-down learning is at its most structured and controlled when it is implemented within the wrapper of a ‘course’, traditionally in the classroom, but nowadays just as likely online or some blend of the two. Formal learning is not necessarily rigid, authoritarian or boring – it will often include games and simulations, drama, outdoor activities and other forms of discovery learning.

Top-down learning is the traditional domain of the l&d professional, acting on authority delegated from senior management, sometimes through the human resources department (most typically when the requirement spans the whole workforce) and sometimes through the line (when the requirement is of a more technical nature). Because it exists to serve the needs of management, top-down learning must by definition be managed in this traditional, hierarchical fashion and cannot be allowed to just happen of its own accord.

To many l&d professionals, top-down learning will be their only concern and the only form of learning that they recognise or even acknowledge. But, as we know, even in the most tightly-controlled organisations, a great deal of learning also occurs on a bottom-up basis, on the initiative of employees themselves, who have their own interests in performing well in their jobs and continuing to be rewarded by their employers accordingly. As we shall see in the following chapter, bottom-up learning is more flexible, more adaptive, requires less support and in the right circumstances is capable of being highly effective. So why should organisations continue to devote resources to top-down learning and take great care to ensure that these resources are applied effectively and efficiently? This question requires some careful consideration and that is where we will start.

Coming next, the second part of chapter 5: Why top-down learning is needed

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

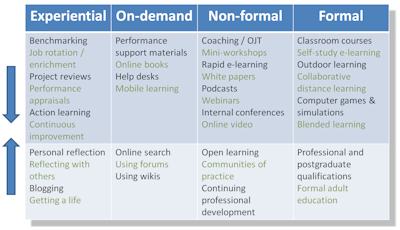

The model in action

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the eighth and final part of chapter 4:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the eighth and final part of chapter 4:

A multitude of opportunities for increasing learning exists within every context, both from the top down and bottom up. The table above shows just a sample of what is available. Some of these opportunities are certainly not new, but may not have been fully exploited in the past. Others – such as blogging, electronic performance support, online books, mobile learning, using forums and wikis, online search, podcasts and webcasts, social networking and blended learning – have resulted from relatively recent technological developments, and have certainly not yet been used to their full potential.

The model can help l&d professionals to:

- consider all the contexts in which learning can take place at work and the opportunities that exist in each of these contexts;

- assess the relative priorities that should be placed on each of the four contexts for a given population;

- provide the right balance of top-down and bottom-up learning for that population;

- create the conditions in which this strategy can succeed.

This process needs to be informed by a thorough understanding of (1) the role that each context plays in an overall l&d strategy, (2) the conditions necessary for learning to thrive from both the top-down and the bottom up, and (3) the range of opportunities that exists to support learning in each case. Much of the rest of this book is devoted to ensuring that understanding.

In the meantime you may be overwhelmed by the abundance of options at your disposal. There’s no doubt that learning and development was a lot simpler when it consisted either of sitting next to Nellie or attending a class. I remember George Siemens once saying that the more choice we have, the more likely we are to choose the familiar option. If that’s the case we’re all doomed. We have waited a long time for the tools to arrive. Now they’re here, the least we can do is try our best to put them to work.

Coming next, the first part of chapter 5: The scope of top-down learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning videos: part 2

![]() In part 1, we looked at the various forms that learning videos can take and the ways they can be used, either as a stand-alone solution or as an element in a blend. We move on to the practicalities of getting a video made, starting with what the film and TV industries call pre-production – essentially all those tasks that need to be completed before you press record on the camera.

In part 1, we looked at the various forms that learning videos can take and the ways they can be used, either as a stand-alone solution or as an element in a blend. We move on to the practicalities of getting a video made, starting with what the film and TV industries call pre-production – essentially all those tasks that need to be completed before you press record on the camera.

Seeing as we are concentrating on the absolute basics of video production, requiring the minimum of technical expertise and equipment, you might feel that pre-production is a bit of a grand topic to be spending any time on. But even the simplest productions need some planning, as we shall see.

Develop your concept

You need an idea. You can’t just press record and shoot the first thing you see. This idea must be compelling to some degree or no-one is going to take the time to watch. So, take the time to consider what you could contrive that would enhance the lives of your audience in some way. In a learning context, that could mean showing how to do something, explaining a difficult concept, or allowing people to share their thoughts and opinions on a matter of some importance.

If we’re talking online video (and probably we are) then you have to figure out how to realise your concept in five minutes or less. That’s not a long time, but it’s all most viewers are prepared to spare. Keeping your video short also reduces the burden on you in terms of the more advanced production techniques you would need to sustain interest over a longer period.

Five minutes is not so long, but your video still requires a beginning, a middle and an end. Think this through up front – don’t expect to be able to fashion all this in the edit.

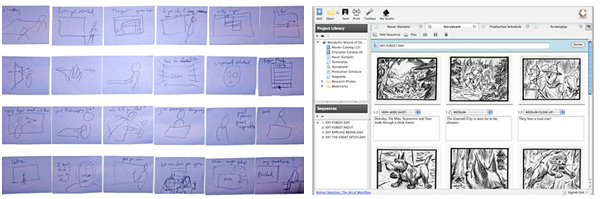

Prepare a script or storyboard

If your video requires narration or acted dialogue then this clearly has to be scripted in advance. Even if you are conducting an interview, you’ll need to prepare the questions and have some idea how you expect the interviewee to respond and for how long. You can prepare a script using Microsoft Word or similar word processing software, or use a specialist application such as Final Draft. Normally a video script will provide some information about the visual content in the left-hand column and the words on the right, although there is no law about this.

Whether or not your video is going to contain narration or dialogue, if you intend it to be visually rich, with many different scenes, camera angles, graphics or effects, then you should seriously consider preparing a storyboard. This goes beyond a script to provide a rough idea of how each shot in each scene should be composed. A storyboard will be a great help both in planning and directing your shoot, reducing the chances that you will have to go back to shoot important elements that got forgotten on the day. You may find you can storyboard adequately using a pack of post-it notes. For something more permanent and sharable, PowerPoint may do the job. And of course there is specialist software available, like the free Celtx.

Find a suitable place to shoot

There are probably four main considerations when selecting a location for your shoot:

- Will it allow you to show what you need to show? If you were looking to demonstrate a task or act out a scene in an authentic setting, then this would be the over-riding issue. If a more contrived setting, such as a studio, will work equally well, then you have less to worry about.

- Will the environment be quiet enough? Without the right sound equipment, a noisy location could completely scupper your chances. If you really must work in a lot of noise, you will need a highly directional mic as close as you can to whoever is speaking. Of course this will not be an issue in a studio.

- Will there be enough light? Time was when every video shoot required dedicated lighting, but modern cameras – even the really cheap ones – cope remarkably well in low light. Having said that, you will always obtain best results when the scene is well lit, so if the ambient light is not likely to be good enough, hire some proper lights.

- Is the location available when you want and at an appropriate price?

Deciding what equipment you will need

Assuming you are intending to distribute your video online then, contrary to what you might think, the camera you use is not going to make a big difference to the quality of the end result. Why? Because practically all cameras – even webcams and the cameras built in to phones – provide adequate resolution for display on a mobile device or in a small window on a PC. Amazingly, many cameras can now record in high definition, which is fine if you are playing back on an HD-compatible display, but pointless otherwise. Don’t underestimate the processing power needed to edit HD video. Your computer will have to handle something like six times the number of pixels than it would with standard definition and up to 20 times the number you need for YouTube. If your computer can handle HD then fine, but don’t expect it to make any difference to the end result.

If you really do need to record at high resolutions and to very high quality, then go for a professional camcorder (you’ll get something great for £1500) or one of the new digital SLR stills cameras with HD capability built in (the Canon EOS 5D Mark II sets the standard here). Otherwise there are plenty of excellent low-cost models to choose from, including what you have in your phone.

Much more important to the quality of the end result is the microphone. There will be one built in to the camera and this may be adequate, but if you want clear speech this has to be of good quality and highly directional. A much better option is to use an external microphone that can be positioned close to the subject. This could be wired or wireless, but does require that your camera has a socket to connect an external mic.

We’ve handled lighting already, which leaves the issue of a tripod. Some cameras have good integrated image stabilisation, but this can’t perform miracles. If you really need a rock-steady camera then support it on a tripod. Simple as that.

Coming up: the fun really starts with the shoot itself

The need for bottom-up learning

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the seventh part of chapter 4:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the seventh part of chapter 4:

Bottom-up learning is managed by employees themselves. Why? Because it is in their interests to gain whatever knowledge and skills they need to perform effectively. A bottom-up approach is needed to address the 80% of learning that is needed 20% of the time. It most needs to be encouraged in those organisations in which there is constant change and fluidity in tasks and goals.

Bottom-up learning is cheaper, more responsive, less controlling, less patronising and altogether more in tune with the times. But it is also less certain, less measurable and less suited to dependent learners who don’t know what they don’t know.

For bottom-up learning to thrive, employees need the motive, the means and the opportunity (just like the perps in the crime novels). They will only have the motive if they are rewarded for effective performance. They will only have the means if employers help them to develop the metacognitive skills they need to learn independently and provide, where appropriate, the right collaborative software tools. They will only have the opportunity if employers are able to foster a culture which encourages self-initiative and does not penalise mistakes.

L&d professionals could do worse in future than to regard bottom-up learning as the default solution, the one they choose routinely except where it is obviously unsuitable. For too long, employees have been spoon-fed their education and their training, and have failed to develop as independent learners to the extent that perhaps they should have done. Those entering the workforce in 2010 have overcome these barriers and have higher expectations. Provide them with the motive, the means and the opportunities and their capabilities are likely to astound you.

Coming next in chapter 4: The model in action

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

A practical guide to creating learning videos: part 1

![]() Video is very much the medium of the moment. Not only do we spend many hours each day watching it on our TVs, it has become an integral part of the online experience. An ever-increasing proportion of the population does not only consume video, it creates and shares it with a world-wide internet audience. Whereas once video cameras cost many hundreds, if not tens of thousands of pounds, they are now integrated for no additional cost in computers, stills cameras and mobile phones. And where once video editing could only be carried out by skilled engineers in elaborate editing suites, it can now be accomplished, often with equivalent production values, with free or low cost software on PCs and even mobile devices.

Video is very much the medium of the moment. Not only do we spend many hours each day watching it on our TVs, it has become an integral part of the online experience. An ever-increasing proportion of the population does not only consume video, it creates and shares it with a world-wide internet audience. Whereas once video cameras cost many hundreds, if not tens of thousands of pounds, they are now integrated for no additional cost in computers, stills cameras and mobile phones. And where once video editing could only be carried out by skilled engineers in elaborate editing suites, it can now be accomplished, often with equivalent production values, with free or low cost software on PCs and even mobile devices.

In a learning context, video provides a compelling means for conveying content, particularly real-life action and interactions with people. Amazingly, it can also be quicker and easier to produce than slide shows or textual content. Sometimes you just have to point the camera, press record, shoot what you see and then upload to a website. Obviously it won’t always be that easy, but you should start with the attitude that `”I’ll assume I can do it myself, until proven otherwise.”

Media elements

In its purest form, a video is a recording, in moving pictures and sound, of real-life action as captured by a video camera. In actual practice video goes way beyond live action, and is capable of integrating just about every other media element, including still images, text, 2D and 3D animation. At the heart of video, however, will always be moving images of some form and an audio accompaniment, whether ambient sound, voice, music or some combination.

Interactive capability

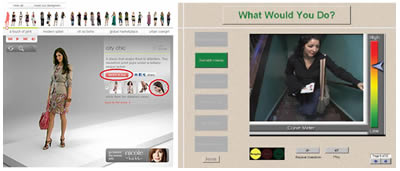

As a general rule, video is not interactive, other than in an exploratory or navigational sense. And for the purposes of this Practical Guide we will be assuming no interactivity. Having said that, it is possible to build interactivity into video, whether that’s on a DVD, a digital TV system or online; it’s also possible to incorporate video material into what are essentially interactive media, such as scenarios and tutorials.

Applications

In its purely linear form, video can be useful for the simple exposition of learning content, such as lectures, documentaries, panel discussions and interviews. It can also function within a more learner-centred context, as a means for providing how-to information on demand, a facility that has been demonstrated with enormous success on YouTube.

As mentioned above, video also has a role to play within the more structured strategies of instruction and guided discovery, as a component within, say, interactive tutorials and scenarios. It is ideal for setting the scene for a case study or demonstrating a skill. It can also be effectively used as a catalyst for discussion in a forum or in a classroom.

Video is a rich medium in every sense. It is highly engaging and can portray real actions, behaviours and events more faithfully than any other medium. However, this comes at a price. Video is also data rich, and consumes vast amounts of bandwidth. On a CD or DVD this causes no problems, but your IT department will certainly want to know if you are going to be distributing video on a large scale over your company network.

So how do I get started?

Enough of the theory. You’re probably keen to get started. You’ll have to wait a week or two but in the subsequent parts of this Practical Guide, we’ll be looking at the absolute basics of:

- pre-production: planning, scripting and choosing your camera

- production: shooting a skills demonstration, a piece to camera, an interview, a lecture/presentation, an acted sequence, an animation – and when to admit defeat and bring in the experts

- post-production: editing; adding titles, music and graphics; exporting / sharing

Coming in part 2: pre-production

The need for top-down learning

![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth part of chapter 4:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the sixth part of chapter 4:

As stated previously, top-down learning happens at the employer’s initiative, and does so because organisations need their employees to have the right knowledge and skills if they are to perform effectively. Whatever the attractions of a more bottom-up approach (as we shall see), some learning cannot be left to chance. Why? Because employees need basic competencies and they don’t always know what they don’t know, where to look for answers or who to turn to; because requirements change (new policies, products, plans), and because employees must be developed to fill future gaps.

However, it is unrealistic for all learning to be managed on a top-down basis, particularly in those organisations where change is constant and knowledge requirements hard to predict. As most top-down learning requires the direct intervention of subject experts and l&d professionals, resources are clearly going to be limited, so priorities have to be made. Top-down learning is likely to be most valuable for the 20% of knowledge that is needed 80% of the time, and for learning that is most critical in terms of risk to safety, budget or reputation.

Coming next in chapter 4: The need for bottom-up learning

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect