![]()

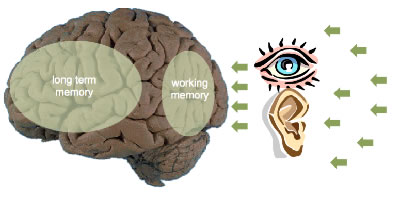

Strictly speaking, reference information isn’t learning content at all, because its purpose is on-demand performance support, not learning. In a performance support context, there is no requirement for the information that is being referenced to be learned, i.e. to be stored in long-term memory. The information is required only to answer a current question or solve a current problem and, as such, it will be processed only in working memory. Because working memory is so limited (current thinking is that humans can hold only 3-5 items of information in their conscious working memory at any one time), it is vital that reference information is extremely clear, simple and concise, minimising the risk of cognitive overload.

Reference information is playing an ever bigger part in our lives. There’s so much we could know and it’s changing so regularly that it really is pointless trying to remember it all – we couldn’t do it if we tried. True, it is still as important as ever that we understand the key concepts, principles and rules that underpin our work, as well as the skills to apply these on a day-to-day basis, but the rest we can draw down as and when it’s needed.

As a learning designer you may be wondering what reference information has to do with you, but you can play a key role. When you design a learning solution, you have to decide what’s course and what’s resource, and in many cases you will share materials between the two. And, as an expert in communication, you are better placed than many to do a good job of putting together reference materials that are clear, concise and usable.

Media elements

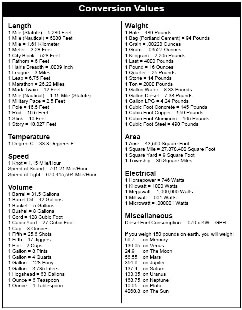

Reference information can utilise any media element, but tends to centre on text. There are good reasons for this. Text is fast to load, it can be quickly skimmed, it can be easily cross-referenced with links and can be copied and pasted with ease. The key with reference information is to get users in, get them to what they want and get them out again as quickly as possible. Text – supported where appropriate by photos, illustrations, charts and diagrams – performs these functions really well.

There are exceptions of course. Some tasks are best explained visually, using video or screencasts with accompanying narration. As long as these are kept short and sweet, they can do the job. As we have dealt with both of these formats in previous guides, we won’t be covering them here.

Interactive capability

Because the purpose of reference materials is just-in-time support and not learning, interactions which encourage users to explore ideas or which assess learning are not relevant. Apart from anything else, they would drastically slow up the user in getting in and getting to the required information. On the other hand, as we shall see in part 3 of this guide, navigational interactivity is critical to good reference materials, whether that’s through search, indexes, tables of contents or cross-references. Some more advanced performance support materials may also allow users to configure the information they want to receive (think of something like a weather or stock price app on a mobile device) or will ask users a series of questions to help them trouble-shoot a problem or narrow down a decision.

Applications

Reference materials fit classically within the exploration learning strategy. As such they are designed not to be ‘pushed’ at the user but ‘pulled’ as required. In the context of a blended learning solution, they supplement courses with easily accessible resources. Whereas historically some 80% of a learning designer’s effort might have been put into the courses and only 20% into providing on-demand resources, we can expect that ratio to reverse in coming years. People no longer expect to have to store loads of information in their heads; they do expect to be able to access it online.

Formats

Reference information can be presented in a number of formats:

- Embedded in a software application: One of the most common requirements for on-demand help is to explain how to use a particular software application, or how to enter appropriate data into that application. An advantage of embedding the help within the application itself is that the information presented can be context-sensitive, i.e. directly relevant to the activity that the user is currently undertaking.

- In a native document format: Much reference information is stored in a native document format such as Microsoft Word. While tools like Word have very sophisticated editing capabilities, they are not best suited to online use. Native files are slow to open and depend on the user having a copy of the application that was used to create them. More importantly, it becomes clumsy to link from document to document and it is all too easy for different versions of the document to be available at the same time.

- As a PDF file: PDF is versatile in that a wide range of applications can save in this format. It also overcomes the need for users to have copies of Word, PowerPoint or whatever other applications were used to create the materials. PDFs are particularly suitable when users need to be able to access information without an online connection or when they want to print materials out. In all other circumstances, HTML wins out.

- In HTML: HTML is the format of the web and, as such, is standard across all computing devices. Web pages are ideal for displaying reference information because they download quickly, can be accessed from any device, and can be kept up-to-date centrally. They can also be easily cross-referenced using hyperlinks.

- As a mobile app: As any smart phone or tablet user can attest, apps are the quickest and easiest way possible to access information. They are particularly suited to situations in which a body of content or an up-to-date information source needs to be accessed very regularly. They score over mobile web browsers which access simple HTML pages online because the way the information is displayed can be designed specifically for the mobile device in question. The application itself is stored locally which speeds up access, and less volatile information can be stored on the device itself, making the information accessible even when there is no internet connection.

So how do I get started?

Assuming you have researched fully what information is needed by whom and in what circumstances, your next job is to choose the format in which the information will be presented. The format will dictate the tools you’ll need:

- Embedded information: Here your best route is to liaise with the developers to see what’s possible and what help creation tools are available.

- Native document format: This is simple enough – just use Word, PowerPoint or whatever to create your materials and then publish in the version most widely available to your users.

- PDF: It used to be you had to purchase special Adobe Acrobat software to create PDFs, but now you’ll find that many of the applications you’re already using can save directly to PDF format.

- HTML: The tools you use here will depend on the infrastructure your organisation already has in place for distributing information. There is probably a content management system in place for your intranet and that’s a good place to start looking. If not, and you’re looking particularly to provide information to support software users, you may want to purchase a system that’s specially designed for creating online help materials. Whatever the case, you do not want to be hand crafting HTML pages. Those days are long over. Creating web pages should be no more complicated than filling in a form.

- Mobile app: Until more easy-to-use tools become available, developing an app is a specialised and highly technical process. For now, best to liaise with your own IT team or engage an external contractor.

Your next concern is how you are going to present the information and that’s where we’re heading next.

Coming in part 2: Presenting reference information