![]() Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 6:

Throughout 2011 we will be publishing extracts from The New Learning Architect. We move on to the first part of chapter 6:

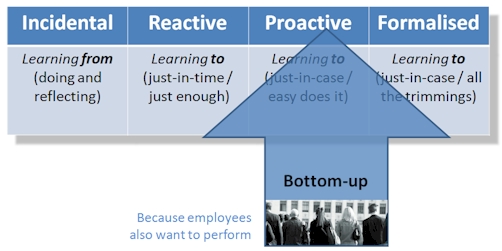

Bottom-up learning occurs because employees want to be able to perform effectively in their jobs. The exact motivation may vary, from achieving job security to earning more money, gaining recognition or obtaining personal fulfilment, but the route to all these is performing well on the job, and employees know as well as their employers that this depends – to some extent at least – on their acquiring the appropriate knowledge and skills.

Bottom-up learning occurs in each of the four contexts that we have described previously:

Experiential: Experiential learning is essentially reflective – ‘learning from’ rather than ‘learning to’. This process can be initiated by the individual without any deliberate action on the behalf of the employer. At its simplest, this might mean no more than sitting back and thinking over events that have occurred, whether these events directly involved the individual or whether they were merely observed. If an event had a negative outcome, the question needs to be asked ‘why did this happen?’ Could the outcome be avoided in future or mitigated in some way. If the outcome was positive, it is just as important to know why. Why can be done to replicate this successful outcome, or to exploit it if it occurs again? The process of reflection becomes interactive when it takes the form of a discussion – talking things over. And it becomes more disciplined when it is made explicit through blogging. Employees can also choose to expand the opportunities they have for learning experiences by ensuring they maintain a healthy work-life balance. Out-of-work activities such as hobbies, travel and voluntary work will often have parallels at work. By maximising the scope for new sensory input, individuals increase the chance that they’ll build valuable skills and insights that they can apply in their jobs.

On-demand: When it comes to just-in-time learning, employees have always needed to rely to some extent on their own endeavours. It is highly unlikely that any employer will be able to predict every item of information that every employee is going to need in every situation, and make that available in the form of some sort of job aid or resource. At simplest, when they’re stuck, employees simply consult an expert, typically the person sitting next to them. Ideally this process will be formalised through some kind of online ‘find an expert’ solution, a sort of corporate Yellow Pages. Increasingly online tools are being made available to support and encourage bottom-up learning at the point of need, notably forums to which questions can be posted, and wikis which can be used to collect together useful reference information.

Non-formal: There’s a number of ways in which employees can set about equipping themselves with the knowledge and skills they need to develop in their roles, without enrolling on formal courses. While each of these methods relies on the employee to initiate the activity, they all tend to require some help from the employer, whether that’s by establishing the appropriate infrastructure or by committing to policies which make opportunities accessible. Some examples include open learning, where the employee takes advantage of learning resources, such as short self-study courses, which the employer makes available for access on demand; social networking software, which allows the learner to establish contacts with others within the organisation who have similar needs; attending external conferences; and enjoying the services provided by professional associations and other external membership bodies.

Formal: You would think that formal courses were an exclusively top-down initiative, but there are plenty of ways in which employees can take the initiative themselves. Perhaps the most obvious examples are postgraduate courses, such as Masters Degrees, and qualifications offered by professional bodies. There are, of course, other less formidable options, such as adult education courses offered by local colleges.

People have many and wide-ranging needs, whether that’s at the level of survival (security, shelter, food, reproduction, etc.), needs of a more social nature (belonging, friendship, recognition) or of a higher order (stimulation, advancement, personal fulfilment, etc.). Directly or indirectly, learning can help an individual to meet many of these needs. To the extent that this learning is reflected in better performance at work, then the organisation has as much to gain as the individual.

While the l&d professional may not determine the ‘content’ of the learning that takes place on a bottom-up basis, they certainly have a role to play in determining the ‘process’. Because it is impractical to meet all learning requirements top-down, it is in the interests of the organisation to encourage relevant, work-related, bottom-up learning. Some of this will happen anyway, regardless of what the l&d department puts in place, but much depends on the right policies and infrastructure being put in place.

Where l&d professionals must be careful, is not being over-prescriptive about the ways in which bottom-up learning occurs. As John Seely Brown and Paul Duquid point out : “The solution to unpredictable demand is systems that are geared to respond to pull from the market and from audiences; built on loosely-coupled modules rather than tightly integrated programmes; people-centric rather than resource or information-centric. There needs to be a willingness to let solutions emerge organically rather than trying to engineer them in advance.”

Reference:

The Social Life of Information by John Seely Brown and Paul Duquid, Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

Coming next in chapter 6: Why bottom-up learning is needed

Return to Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5

Obtain your copy of The New Learning Architect

Skip to content